The powerful records of the Greater New York Conference on Soviet Jewry (GNYCSJ), a crucial addition to the extensive Archives of the American Soviet Jewry Movement held at AJHS, testify to the harrowing travails of Soviet Jewish activists, refuseniks, and Prisoners of Conscience, individuals who were denied permission by Soviet authorities to emigrate to Israel, primarily, or to other destinations and, subsequently, experienced disenfranchisement, persecution, imprisonment, and torture over years or decades. The archives of GNYCSJ, which served as the coordinating body of Soviet Jewry activities for more than 85 constituent Jewish organizations and community groups through the New York metropolitan area, detail both the scope of the advocacy efforts of American Jewish organizations and the courage of individuals and networks fighting for change from within the Soviet Union.

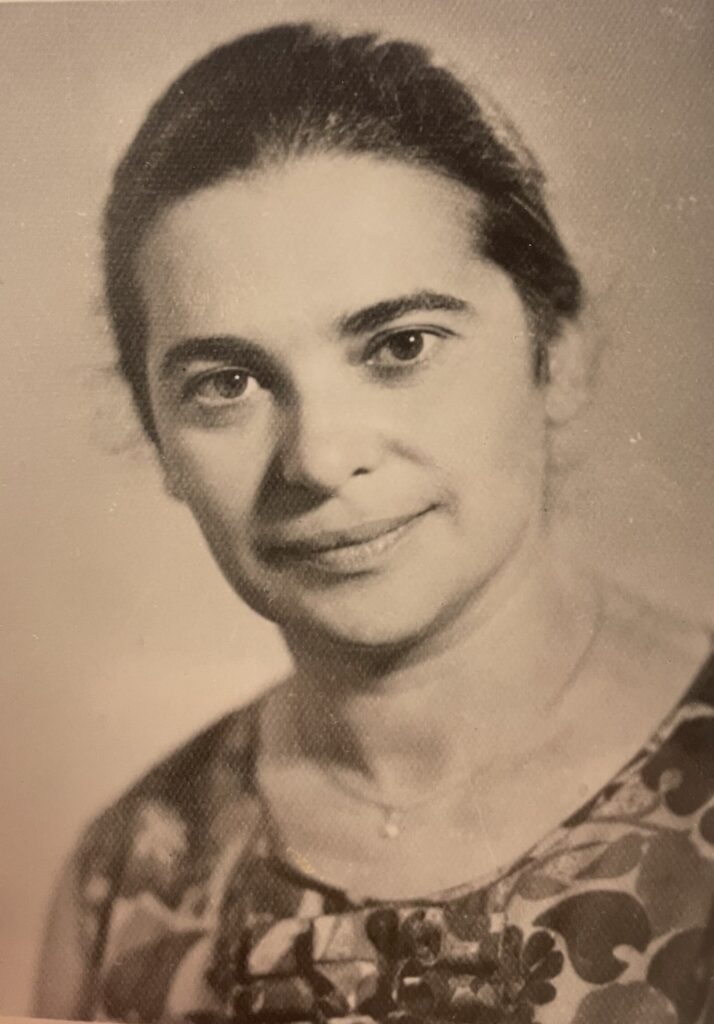

One of those activists was Ida Nudel (1931-2021), a Russian Jewish-Israeli activist who was a major figure of the Soviet Jewry movement during the Cold War in the 1970s-1980s. She was known as the “Guardian Angel” for refuseniks and Prisoners of Conscience, who were also called “Prisoners of Zion.”

After the Dymshits-Kuznetsov hijacking affair (also known as “Operation Wedding”), an unsuccessful hijacking on June 15, 1970 of an empty aircraft by 16 Soviet refuseniks in an effort to flee to the West which garnered worldwide attention to the human rights abuses inflicted upon Jews in the Soviet Union, Nudel applied for an exit visa to move to Israel. Nudel’s application was refused on the purported grounds that she had access to state secrets from her previous employment at the Moscow Institute of Planning and Production. This tactic was a routine one utilized by the Soviet authorities to deny visa application from Jews who wished to emigrate, claiming that the applicants possessed “state secrets” if they occupied positions as engineers or mathematicians, for example, forcing them to wait for a number of years before re-applying, and rejecting their applications again.

In response to being denied emigration, and in protest of ongoing human rights abuses against other refuseniks, Nudel organized a hunger strike in 1972 at the offices of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in Moscow to protest the imprisonment of refusenik Vladimir Markman. The police ended the strike after four days, but she continued her activism, spearheading a letter-writing campaign to other prisoners in several locations to ensure that they would not be forgotten. She remained informed about prisoners’ locations and circumstances through the radio, reading newspaper accounts, and maintaining an extensive network of correspondents throughout the Soviet Union who bartered with guards to convey amenities like underwear, vitamins, and chocolate to prisoners.

Nudel said that she felt compelled to act on behalf of thousands of Soviet Jews “who have submitted documents for emigration and have become ‘non-persons,’ are ostracized and slandered, libelled, harassed and persecuted, and have their dirty linen shaken in public, but also for the hundreds of thousands of Jews who are waiting for a better state of affairs, when it will be possible without fear for their own welfare or for the welfare of their children, without the fear of falling into the trap of ‘refusal’ – that dreadful invention of the KGB – to hand in their documents and leave.” Nudel’s statement was quoted in the article “Ida Nudel’s Response,” provenance unknown.

Nudel’s friend Yehudit Nepomniaschy Levin, who later emigrated from Odessa to Israel, spoke warmly of Ida’s devotion to others: “She would send clothing to people and seemed to know exactly what their needs were. She even helped those who came just for personal advice, such as whom to marry. She was so busy giving to others that she neglected herself.”

Nudel lost her job because of her activism, and eventually was sent into exile in 1978 to a Siberian village, Krivosheino, for four years after she unfurled a banner from her Moscow apartment that read “KGB, Give Me My Visa to Israel.” In Krivosheino, she first worked in a factory, as the only woman, and later as a night guard. Despite being in exile, her activism did not abate.

Nudel was released from exile in 1982; however, she was still barred from emigrating. By law Soviet citizens were required to obtain permission from the authorities if they traveled internally. She was often denied even this permission.

Nudel’s sister, Elena Fridman, who had previously been permitted to emigrate, conducted global advocacy on her behalf. While Nudel was still living in Moscow, she was visited by the actress and activist Jane Fonda in April 1984, on the occasion of Nudel’s 53rd birthday. This meeting was arranged by the American political activist and publicist Stephen Rivers. Upon returning to the United States, Fonda told reporters that she had appealed to Soviet officials on Nudel’s behalf, and that Nudel shared that the visit had given her strength and affirmed that her ordeal was not forgotten. The two became friends, and Fonda campaigned for Nudel’s release.

In October 1987, Nudel was finally issued an exit visa. She made aliyah to Israel, on a private jet supplied by Armand Hammer, a wealthy industrialist with ties to the Soviet Union. Upon her arrival in Israel, Nudel was welcomed by thousands of supporters, including her sister Elena, Fonda, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzak Shamir and Foreign Minister Shimon Peres. Swedish actress Liv Ullman, whom Fonda had enlisted as part of the campaign for Nudel’s release, portrayed Nudel in the 1987 film Mosca addio (Farewell Moscow).

Nudel settled in Karmei Yosef with her sister and wrote her autobiography entitled A Hand in the Darkness, which was subsequently translated into English in 1990. Around 1991, she founded an organization called Mother to Mother, which provided after-school programs and resources for at-risk Russian-speaking children from immigrant families, many of whom were single-parent families.

When she died at the age of 90 in 2021, Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett paid tribute to Nudel in a statement which held her up as “an exemplar of Jewish heroism for us all.”

AJHS gratefully acknowledges the support of the National Historical Publications and Records Commission in processing and making available these historic materials.

Sources

Hoffman, Stefanie. “Ida Has Come Home.” Kol Emunah Vol. 1, No. 2, 1998.

Gilbert, Martin. “Ida Nudel’s Response.” Unknown Newspaper.

Roberts, Sam. “Ida Nudel, ‘Angel’ to Soviet Jews Seeking to Flee, Dies at 90.” The New York Times (New York), September 16, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/16/world/middleeast/ida-nudel-dead.html.

Wikipedia. 2023. “Ida Nudel.” Wikimedia Foundation. Last modified September 27, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ida_Nudel.