Dr. Semyon Gluzman (b.1946) [also known as Semen Fisheliovych Hluzman] is a Ukrainian psychiatrist, human rights activist, and the founder and president of the Ukrainian Psychiatric Association. He was also a Prisoner of Conscience during the Cold War, who bravely criticized the Soviet Union for weaponizing psychiatric treatments against imprisoned political dissidents and activists.

The range of abuses Gluzman documented included deliberately dosing prisoners with drugs which would impair their mental faculties; holding them against their will in institutions; and inaccurately diagnosing prisoners with psychiatric disorders to discredit their activism. Gluzman disseminated his work through samizdat pamphlets, writings which were disseminated by activists in the Soviet Union through underground channels. He would also refuse assignments to work for Soviet authorities in a psychiatric hospital where political dissidents were languishing because, as he wrote, “Psychiatry is a branch of medicine and not of penal law.”

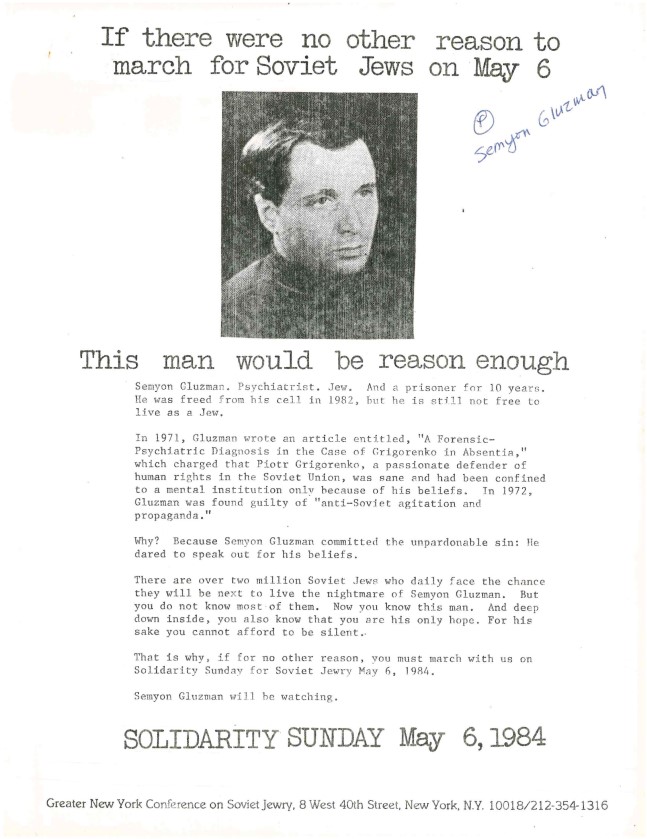

In 1971, he authored a report on Petro Grigorenko (1907-1987), a Soviet Army commander who later became a dissident, testifying that Grigorenko was being abused for political reasons. While Gluzman’s report may have resulted in Grigorenko’s release the following year, Gluzman himself was sentenced to seven years in labor camp and three years in Siberian exile for “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.”

In a 1974 letter to his parents while imprisoned in a labor camp, Gluzman writes “they are murdering me as a person and as a living creature,” encountering starvation, grueling work duties, and being forced to do exercises while naked in freezing conditions. He also describes the abuses suffered by his fellow prisoners, such as a 62-year-old man who has been imprisoned for 22 years, and attempted bribes from prison officials to get him to retract his condemnation of psychiatric abuses.

His words to his parents also movingly describe his commitment to his Jewish faith: “I am a Jew, and my Judaism consists in more than memory – the memory of the victims of genocide and of the persecutions caused by prejudice become dogma. My Judaism lies in the knowledge of our people as they are known today, with their own state, their own state, and happily, their own weapons.”

News of Gluzman’s imprisonment was covered in the American media; for example, The New York Times documented his case in a 1974 article titled Doctor Decries Psychiatric Jails. A number of professional psychiatric associations advocated for his release, including the the Rockland County Mental Health Association in Pomona, NY, which wrote to President Gerald Ford in 1976 to request Gluzman’s release.

The visibility of Gluzman’s campaign against psychiatric abuses of dissidents in the Soviet Union eventually galvanized the formation of committees by international and American psychiatric associations, such as the Medical Society of the State of New York, to document and condemn such abuses and to advocate for corrective measures to protect dissidents.

In 1982, Gluzman was released from exile. After his sentence, he tried to emigrate to Israel with his wife Irina, but was denied. He remained in limbo for many years in his native Kyiv while trying to apply for an exit visa; Gluzman suffered harassment and beatings from Soviet authorities, and was barred from working as a psychiatrist during this period (he worked instead as a pediatrician).

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Gluzman became a Ukrainian citizen, where he still lives. He has received numerous awards from international psychiatry associations for his stanch commitment to ethical psychiatry.

The primary sources referenced above are part of the files on Dr. Semyon Gluzman in the Greater New York Conference on Soviet Jewry (GNYCSJ) archival collection. These files, which include additional correspondence, press and media materials, and ephemera such as flyers from the Solidarity Sunday protests, detail GNYCSJ’s efforts to collect, evaluate, and disseminate information on developments in the Soviet Union, on individual refuseniks and prisoners of conscience, and on the Soviet Jewish activist movement overall.

AJHS gratefully acknowledges the support of the National Historical Publications and Records Commission in processing and making available these historic materials.