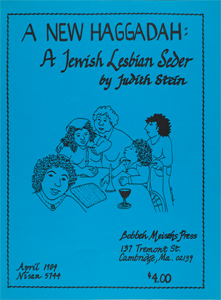

In this lesbian Haggadah, women are the both the heroes of, and the primary actors moving the story forward.

In Judith Stein’s “A New Haggadah: A Jewish Lesbian Seder,” she openly and directly separates both herself and her community from the concept of the divine. On pages ii-iii, she writes:

“I decided what to include based on several ideals. First is my commitment to the preservation of Jewish ritual and culture. Although I have no interest in god or prayer, I have a strong commitment to Jewish culture, and the survival of a diverse Jewish community. Jewish culture springs from religious liturgy and practices, and I have tried to preserve whatever is possible from the traditions. Thus, in writing this Haggadah, I … looked beyond the meaningless, offensive, or sexist language to the original intent … I also wanted this Haggadah to reflect Jewish lesbian culture positively, and to include the contribution of Jewish women to our survival as a people … Finally, this Haggadah is consistent with my own personal values. There are no blessings, no reference to god, and no mention of divinely-wrought miracles … Pesach has tremendous possibilities for meaning in the life of any Jewish lesbian; each woman must search for those rituals that create an honest, spiritual expression. This is definitely a process of trial and error; as we evolve and change, so will some elements of our Pesach observance. What is important is not that we do it perfectly each time, but that we never give up that search.”

In accordance with this philosophy, Stein interprets the holiday through an anti-oppression lens; one especially meaningful to a lesbian Jewish women living in 1980s America. Further, she centers the concept of liberation not only in terms of the Jews as an ethno-religious minority, but lesbians as a minority even within that group.

In Stein’s Haggadah, all notions of divine retribution, violent death of the oppressor, and traditional victory narratives are dispensed with. Instead of the traditional story of Moses parting the Red Sea, Stein includes the poem, “To Her Grandchild,” written by Janet Berkenfield, 1982, on page 9 of the Haggadah. An abridged version of this poem reads:

“You asked me about the sea … I remember, though I try to forget, it was so terrible.

In the mouths of our storytellers the sea crossing has become a miracle.

It was a nightmare.

I still see the dead Egyptians, hundreds of them in the water …

Moses promised us a wonderful thing … but it was terrible.

… The children were screaming that day; the wind so strong, the mud so thick we could scarcely walk.

… We knew the Egyptians were behind us, but the sand was in our eyes the wind roaring, pounding us, then—it stopped, for a moment there was nothing; everything was still … and then we heard them,

they were children’s cries: the Egyptians.

We saw nothing … but we heard them; heard the water, the horses neighing.

Our children began to wail again and as the sand settled we saw them in the water, drowned, caught in the reeds.

They were children! Young boys in their uniforms.

… Sarah, my neighbor, saw her owner’s son and I, a palace guard who helped me pack and gave me food for the journey.

Everyone saw a face they knew.

And such wailing then! It went on and on grief and fear, we were so tired, where was Moses, when would he take us home?

Then gradually, through the crying, Miriam’s thin sweet voice—trembling, her tune spun in the air and floated over us.

… As our fear left us, we began to sing with her; then Moses took up the song and the men began to chant of victory and the death of the mighty Pharoah …”

In this poem, the crossing of the Red Sea is transformed into a horror story. It is a tale of love, strength, grief, and community, in which Moses is little more than a name, a distant side character, emotionally removed from the drama and humanity of the narrative.

As the Haggadah continues through the Seder ritual, Stein fills it with stories and writings of courageous Jewish women, from Judith to Zivia Lubetkin, the only female leader of the Jewish resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto. In Stein’s vision of Passover, women are the center of the story, and the actors with the greatest agency within the tale. In re-centering and re-interpreting the Passover story, Stein implicitly urges her readers to reframe their own lives and stories, and ask themselves whether they are active agents of liberation, or bystanders on the margins of history.