To Ray Frank, female Jewish leadership, organization, and action was the ultimate enactment of Jewish motherhood.

Originally posted March 5, 2021

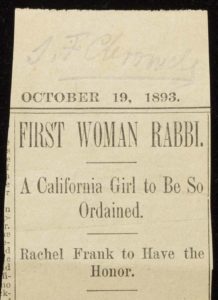

The “Girl Rabbi of the Golden West” was a boundary breaking sensation back when telephones were still a new invention. But if you were to have asked her, she would have denied her role in breaking boundaries, or disrupting the traditional order of men, women, and public life.

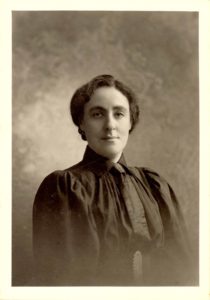

Photo of Ray Frank, taken in 1900. From Collection P-46.

Rachel “Ray” Frank Litman (b. April 10, 1861, San Francisco) never set out to be a rabbi, nor was she ever officially ordained as one. In fact, she began her career as an educator, with a stint of time spent teaching in the small mining town of Ruby Hill, Nevada. In 1885 Frank moved to Oakland, California, where she took philosophy courses at UC Berkeley, taught literature and elocution, and delivered lectures on Bible Studies and Jewish History Oakland’s First Hebrew Congregation’s Sabbath School.

It wasn’t long before her lectures began to draw crowds of curious adults, intrigued by her presence as a speaker. Before long, she was invited to serve as principal of the Sabbath School. But while she was teaching and studying in Oakland, she was simultaneously writing for Jewish and secular newspapers across Northern California and the Pacific Northwest.

In 1890, a writing assignment took her to the town of Spokane Falls, Washington. She arrived the day before Rosh Hashanah, but found, to her dismay, that the town—though home to a large Jewish population—had no synagogue. Word of her disappointment made its way to the ears of a wealthy member of the Jewish community, who was already a great admirer of her work. He told her that he would gather a congregation if Frank was willing to deliver a sermon.

That service, held at the Opera House, drew a crowd of over 1000 people from the Orthodox, Reform, and even Gentile populations of the town. And before this crown she delivered the sermon, “[On] The Obligations of a Jew as Jew and Citizen,” becoming the first Jewish women to formally preach from a pulpit in the United States. The community asked her to stay through the High Holidays, so that she could also deliver a Kol Nidre sermon, and she agreed. Word spread quickly, and soon she was fielding invitations to speak up and down the West Coast, from San Diego to British Columbia. She had so many speaking invitations, in fact, that she required the services of a booking agent.

Her sermons and speeches regularly drew crowds numbering in the thousands, and she was frequently called to help establish congregations. Newspapers closely followed her career, often reprinting her sermons in full. Yet, Ray Frank, despite her affectionate media nicknames, had no interest in becoming a rabbi. In fact, she believed that it would be improper for a woman to do so. And indeed, Frank’s writings increasingly focused on the importance of Jewish women in the domestic transfer of Judaism from one generation to the next, and in Jewish organizational life.

She served as a delegate to the first Jewish Women’s Congress in the 1893 World’s Fair, where she delivered both the opening prayer and a paper praising Jewish women’s traditional roles as wives and mothers, while simultaneously emphasizing that Jewish history was replete with female leadership.She continued to turn down offers to take up work as a rabbi, and came out in opposition to the women’s suffrage movement in 1894, frequently speaking out against the idea of married women working outside the home.

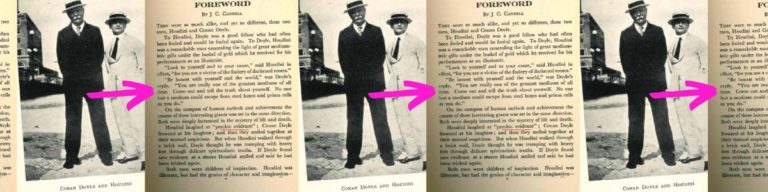

By 1898, Ray was exhausted from her years of traveling and speaking and writing and took a break to tour Europe. When in Munich in 1899, she made the acquaintance of doctoral student Simon Litman. Frank and Litman were married in London on August 14, 1901, and moved to California in 1902, where he taught marketing and merchandising at Berkeley. Once married, Ray Frank Litman enacted her

politics; she rarely accepted speaking invitations, greatly curtailed her writing career, and devoted most of her energy to keeping house and her role as a faculty wife.

Simon Litman took a teaching position at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana in 1908. When they arrived, Ray was uncomfortably reminded of her past celebrity. Yet, she hardly demurred from engagement in Jewish life. She started a Jewish history study circle for students, worked with the Jewish student groups which would become the Hillel movement, and helped organize the Sinai Temple sisterhood in 1922. She passed away in on October 10, 1948 in Peoria, Illinois, at the age of 87.

What makes Ray Frank Litman a fascinating figure is the apparent contradictions in her life, career, and politics. She led and founded congregations, yet strongly objected to women taking on the traditionally male role of rabbi. She believed that married Jewish women, and all married women, belonged in the home, yet tirelessly advocated for these same women to become organization leaders in their communities. Yet, to Ray Frank, none of these things—her leadership, her writing and speaking career, her organizational work—stood in contradiction to her views on traditional gender roles. As educated middle class nineteenth century women embraced their roles of keepers of domesticity, and transmitters of culture and religion to the next generation, they understood their domestic sphere as one which allowed for public life so long as that public life aligned with their domestic roles.

For Frank, writing and speaking about the importance of Jewish women as the location of the intergenerational transmission of Judaism was the same as taking on those roles, but instead of transferring Judaism to her children, she was inculcating an idea of Judaism and Jewish life to her audiences. Likewise, her urging of Jewish women to stay in the home while simultaneously encouraging them to take on leadership roles in the Jewish community was not a contradiction, but merely an enactment of the idea that the domestic sphere extended into the public, as the community served as a larger version of the family. To Ray Frank, female Jewish leadership, organization, and action was the ultimate enactment of Jewish motherhood.

This said, it is important to note that Ray Frank Litman was not stubbornly set in her ways. Despite her previous opposition to women’s suffrage, in 1922 she founded the Champaign County League of Women Voters to ensure that female voters arrived at the polls as informed as possible. It wasn’t a dramatic change, after all, for if women needed to act as mothers to their communities, why should those communities not include the largest community of all: that of the United States of America?