“If you lend money to My people, even to the poor among you, do not act toward them as a creditor; you shall not charge them interest.” – Exodus 22:24

“You shall not lend him your money at interest, or give him your food for profit.” – Leviticus 25:37

The American Jewish Historical Society is pleased to announce one of its newest institutional collections, the Records of the Hebrew Free Loan Society, 1892-2010. “Gemilath chesodim” is the Jewish concept of “giving loving-kindness,” which can be expressed in several ways, including helping others in financial need. At the Hebrew Free Loan Society of New York (HFLS), this concept centrally informs their mission to provide interest-free loans. The organization shares its lineage with Jewish landsmanshaftn societies formed by Jewish immigrants from the same villages, towns, and cities in Central and Eastern Europe, also known as mutual aid benevolent societies. These societies were established or re-formed in the United States, especially during waves of immigration in the 19th and early 20th centuries and were incorporated as financial entities with boards of directors and membership in different locations, particularly in New York City.

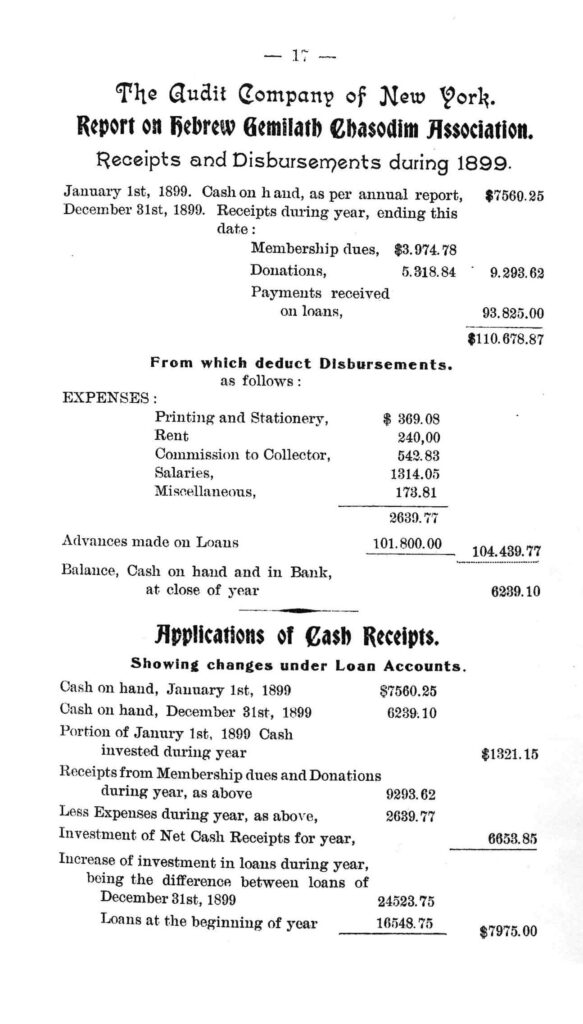

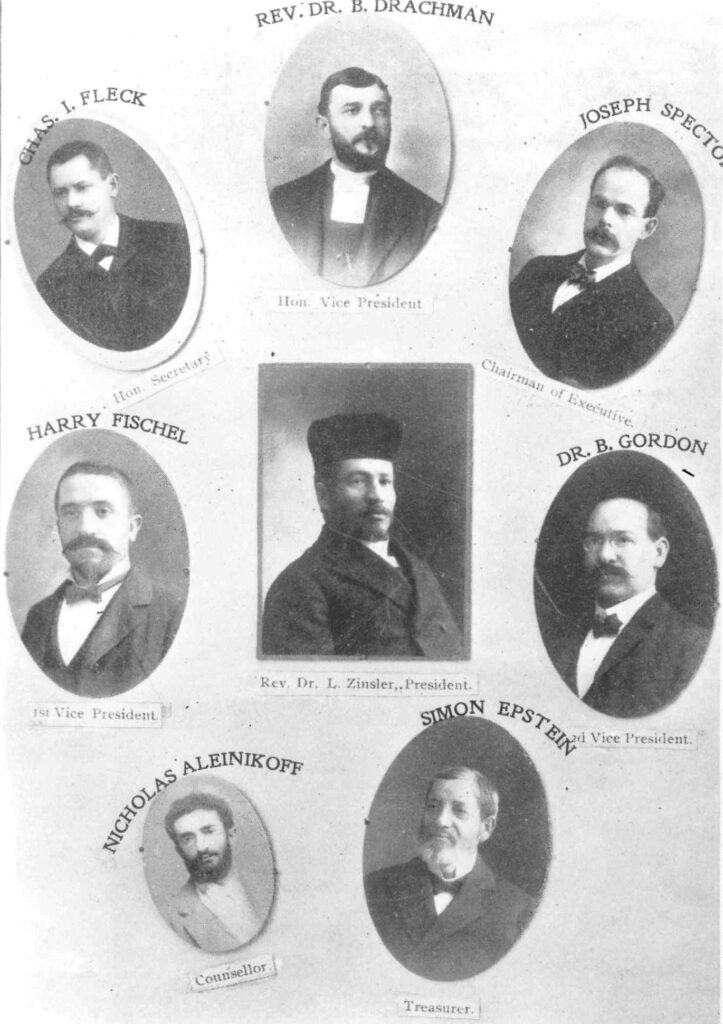

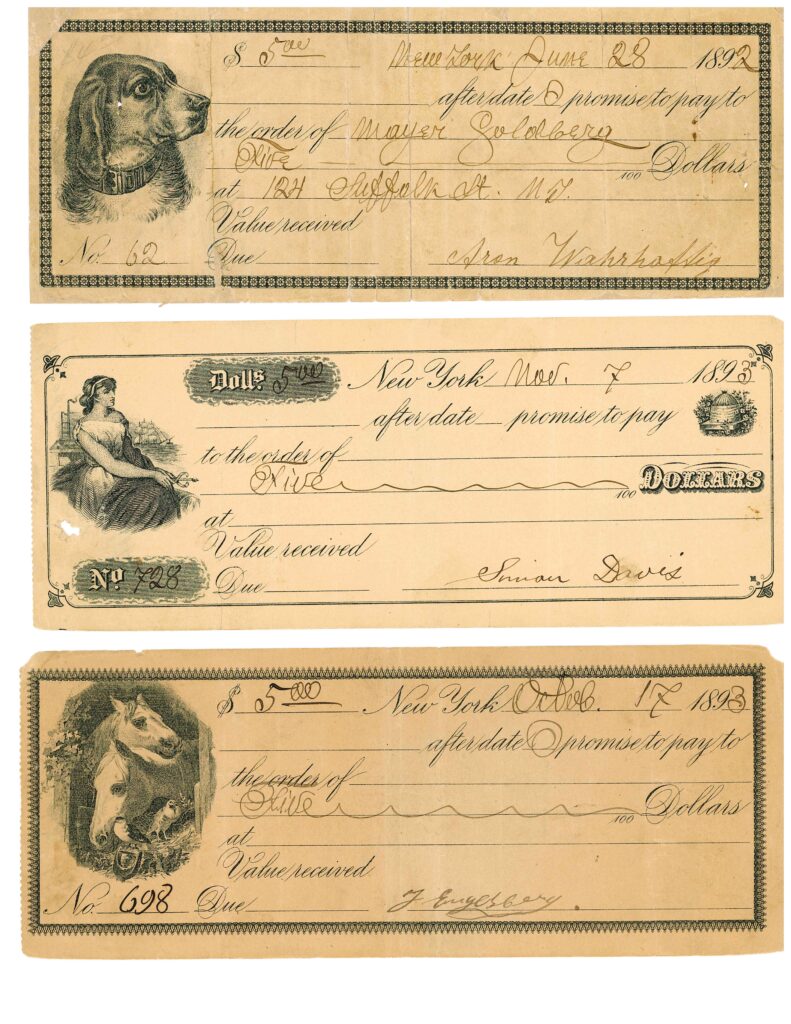

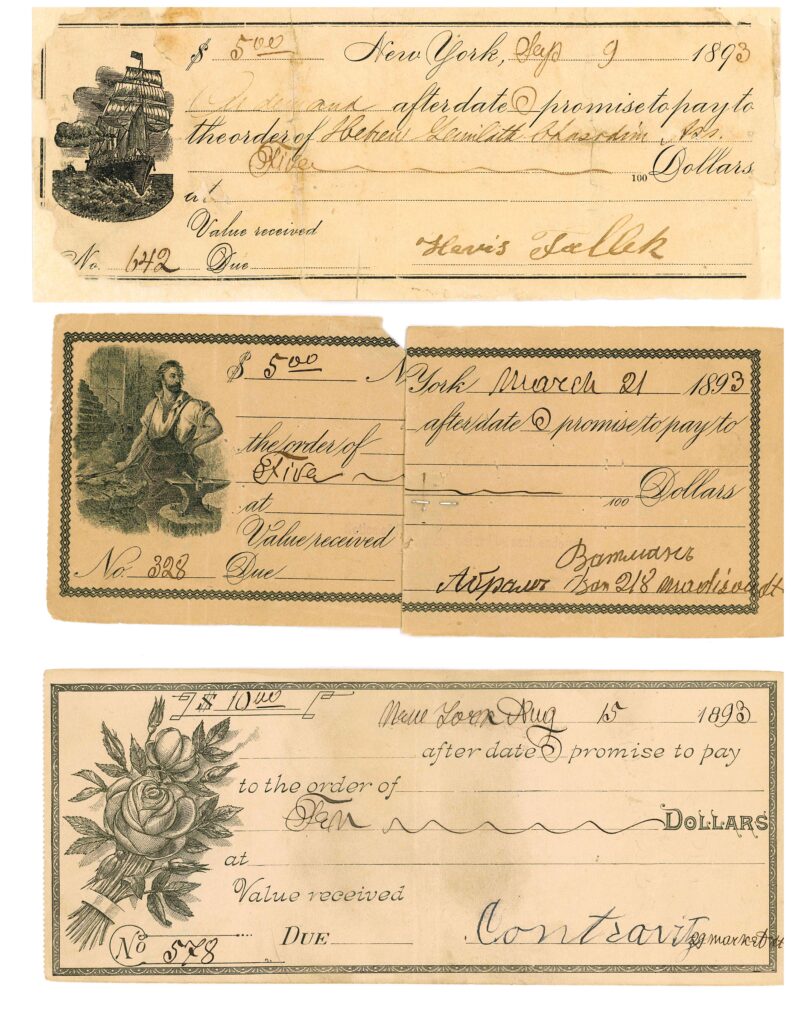

The earliest founding records in the HFLS collection are the first Constitution and By-Laws published in 1894 and a “Five Years Report” from circa 1897 chronicling the organization from 1892-1897. The exact date of the HFLS is elusive: its incorporation was in 1893, though the first organizing meeting was held in 1892. HFLS published reports note that eleven (or ten in some accounts) men met at the Wilner Synagogue located on Henry Street, where they gathered $95 to provide interest-free micro loans to those who needed a temporary helping hand. Two major “Great Benefactors” are noted in HFLS publications: Jacob Schiff, a scion of the Jewish community in terms of guidance and funding (and founder of the AJHS), and Adolph Lewisohn, investment banker, philanthropist (and grandfather of Frances Lehman Loeb). Rabbi Leopold Zinsler as the first president is also noted, as is Julius J. Dukas, the fourth president of the organization, from 1906 until his death in 1940. Joseph Durst, a leading real estate magnate who arrived in the United States as a poor man before creating the Durst Organization, served as president from 1945 to 1967.

The object of the organization’s mission was “to loan money to poor people without charging any interest or any expense whatsoever.” The HFLS Constitutions and By-Laws stated no barrier to race or creed in issuing loans, but only to “organize a society whose object shall be to loan to those in need certain sums of money instead of giving alms, and thus assist respectable people, whose character and self-respect abhor the thought of receiving alms, to overcome the difficulties in their struggle for the means of existence…”

The HFLS stressed non-sectarianism in its loan policies, and as noted by Jenna Weissman Joselit in the HFLS history, Lending Dignity, that the, “the 30th annual report of 1922… carried the logo “We Lend to All Without Distinction of Creed or Race,” and the 1923 31st annual report reading, “We Lend to All without Distinction of Nationality, Religion or Race.” The Five Years’ Report of 1897 includes a rough breakdown by nationality (but does not note whether they were of Jewish descent): “Roumanians, 250; Americans, 175; Austrians 725; Englishmen, 75; Germans, 265; Russians, 1,275, [and] Hungarians, 527…” and later reports stressed that certain occupations were normally not held by New York City Jews such as priests, policemen and tenement house inspectors, which are reflected in the restricted HFLS promissory notes. The 1913 21st Annual Report lists two pages of “various trades of borrowers” and numbers of loans received by each type of occupation.

As an organization, the HFLS is not considered a bank nor a credit union, but a benevolent loan provider. This was difficult for some observers to grasp, Weissman Joselit notes that “Critics had difficulty reconciling the Society’s overt and stated policy—to serve as a social welfare association—with its highly original practice of loaning money to the worthy poor without charging them a corresponding fee…” the efficiency of HFLS was questionable for those who were used to loans with mandatory interest payments. Jacob Schiff, through speeches and monetary support, encouraged the public to view the HFLS favorably as an organization, leading to donations from the Baron and Baroness de Hirsch, Leonard and Rosalie Lewisohn and support from lawyer Louis Marshall.

In 1917, the HFLS joined, along with other Jewish-based communal organizations, as a constituent of the Jewish Philanthropic Societies of New York City (eventually becoming the United Jewish Appeal (UJA)-New York Federation). From 1968 to 1972 the HFLS began making loans to yeshivas and day schools as well as expanding to home down payment loans. During this same era, special needs programs were set up for small emergency loans for senior citizens, those who needed funds for summer camps and those who were unable to find qualified endorsers for loans. In 1981, the HFLS began a student loan program and in 1982, the organization established loans to nursing students. During the movement of Soviet Jewry from Russia and its former Republics to the United States from 1989-1994, the HFLS worked with the New York Association of New Americans (NYANA) to offer small sums to resettle emigres into apartments and help with bills until employment could be found.

Presently, the Hebrew Free Loan Society has loan programs for adoption and fertility treatment costs; debt consolidation; healthcare expenses; education (undergraduate, professional or vocational training and private special education); purchase of a Mitchell-Lama cooperative apartment (a city-run housing program for lower-income New Yorkers); small business startup and expansion; and security infrastructure improvements for Jewish institutions. The most frequently-accessed program is for general needs, providing support for people facing any kind of disruption in income or sudden increases in expenses.

The organizational founding records of the HFLS are available for research. The finding aid to the collection may be found here.