“Our Heavenly Father, on this day of my Bar Mitzvah, bestow in me sound thought and judgement to do my part as a Jew and as an American citizen. Help me also to understand the principles of my religion and to shape my life on its teachings of fairness, morality, love, and peace… This country of my birth; this true haven of democracy: America, bless it also and let your love, mercy guidance and bounty cover this land from sea to sea. Bless its inhabitants but above all this, give the people of this country the strength to know the principals of democracy and by knowing these truths let I and every other person land remain free.” —Robert Allen Simon (1942-1969), Bar Mitzvah speech at the Israelite Center, Miami, Florida, January 19, 1955

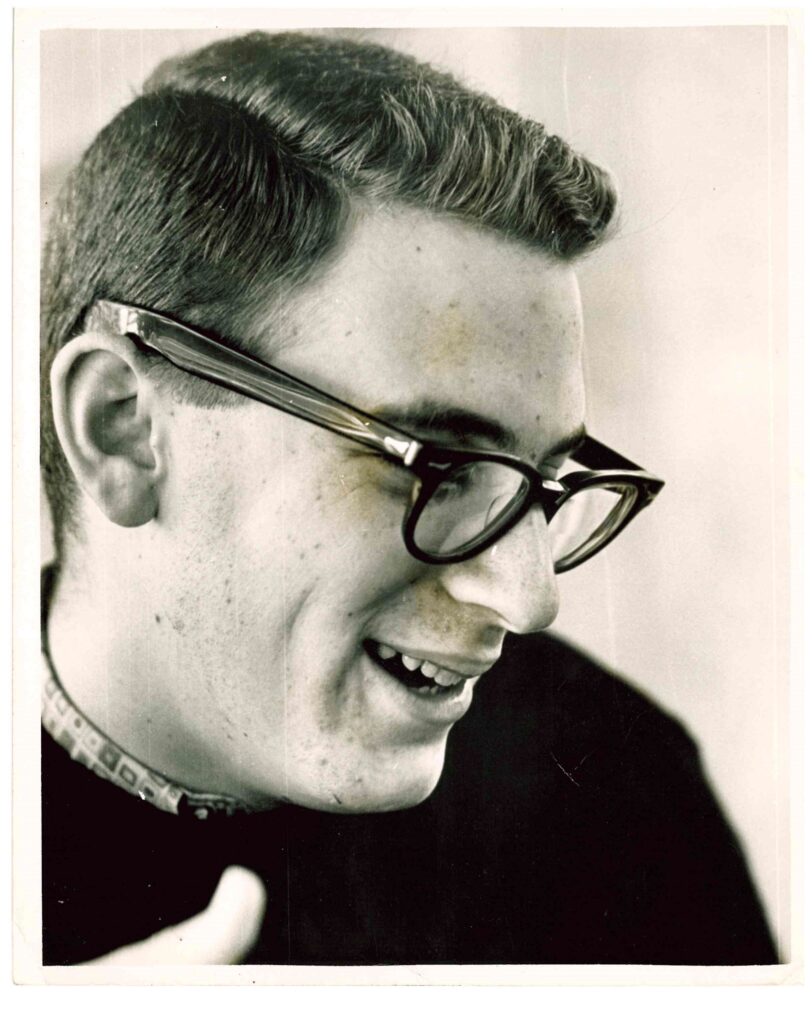

April 30, 2025, will be the 50th anniversary of the United States leaving Saigon, now known as Ho Chi Minh City, at the end of the Vietnam War. Here we take a brief look at the short life and writings of Robert “Bob” Allen Simon, who, in November 1967, was one of several men who burned their draft cards at Foley Square in New York City. They called themselves, “The Resisters.”

On September 23, 1958, Robert wrote to his parents regarding the classes he had just registered for at Stetson University in Florida, which included American History, Intermediate French, Christianity and Western Thought, Biological Science, Honors English, and R.O.T.C. In that same letter he wrote, “I start R.O.T.C. Monday. I can’t wait. The Major (our pot-bellied leader) told us that if we were good students we would get to fire the 75 mil recoilless rifle our very first year. My wildest dreams have become flaming reality. I’m overjoyed.” In November, Bob wrote to his parents that he was invited to the Dean’s home where they discussed Bertrand Russel’s 1950 Nobel Prize speech, “What Desires Are Politically Important?” and the week after they were discussing “progressive jazz.” “All very stimulating,” he wrote.

After leaving Stetson later in Fall 1958 for personal reasons, Robert applied to Bard College. In his admission cover letter he wrote about his organizational work with the B’Nai B’Rith Youth Organization, “These years have been a revelation of how individuals use a group to fulfill their own needs, how the organization always wins in the end by using the individual and of how much enjoyment there lies in occasionally working, thinking, socializing and conversing and the double tempo of conventional life.” On the other hand, Robert was also “bitterly disgusted at the apparent apathy about social action that gripped the people I addressed. This disgust has also been an education, a temperance of optimism and a source of concern to me.” He continued that he was interested in the career of Senator Huey P. Long and was reading All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren expressing a desire to study English literature and History. This admissions letter gives us great insight into Simon’s personality, and while he did not attend Bard but became a student at University of Miami, it feels fitting that he became a writer for the university newspaper, the Miami Hurricane.

Simon was an arts and entertainment writer for the Miami Hurricane in 1960, with a column reporting on a lecture series by Dr. Virgil Barker, a former art history professor at the university, regarding the comparison of abstract and religious art. Between 1960 and 1963, Simon would continue to write about arts and entertainment, but as 1962 ended, his column took a definite turn when he wrote about the California governorship race between Richard Nixon and Democratic opponent Pat Brown, writing what would become a refrain of young people for generations to come: “…The obvious key to the unimportance of the whole business is that both parties are engaged in spending vast amounts of money to create attractive personalities who wish to have no business with anything as messy as significant controversy…new [elected officials] won’t be any more helpful than the old bunch…” While he was still writing about the arts, on March 1, 1963, under the headline, “Vietnam War Gets Hotter,” he lamented over strained relations between the United States and Vietnamese allies, writing, “Charges of corruption, official brutality, inefficiency and a lack of vigor in prosecuting the war have all been leveled… in recent months… The need for vast changes in official policy by both American military advisors and the State Department.”

Simon never finished his degree at Stetson nor the University of Miami. He would eventually move to New York City and attend the New School for Social Research, graduating with an undergraduate degree in 1968. His writings at the New School included two major school papers, one entitled American Socialism and German Social Democracy: 1890-1914; The Proletarian Response to Nationalism and several extant shorter papers, on topics such as Francis Bacon on politics and government, U.S. policy on Spain during the Spanish Civil War, and on “Marat/Sade’s Revolutionary Audience,” a 1967 play by Peter Weiss which depicted a theater of cruelty and absurdity, asking whether “true revolution comes from changing society or changing oneself.”

In November 1967, Simon became one of four members of The Resisters who either burned or returned their draft cards, with Simon appearing in the New York Post on November 8, with a photo caption reading, “Bob Simon holds up what’s left of his draft card after he burned it in Foley Square.” Simon was declared 4-F (unfit for service due to eyesight), and as such, burned his classification card as opposed to his actual draft card. On July 9, 1969, Simon appeared in the case of the United States vs. Robert Allen Simon in a trial that found him guilty of the crime charged but placed on probation as he was officially 4-F and that on the date of his offense, the date of his draft card had expired.

Unfortunately, Robert Allen Simon would live only a few more months after his trial. He and two other New School students, Steven B. Arcady and Ann Weinberg, died in a car accident in Massachusetts. On September 9, 1969, Bob’s probation officers, Chief Arch E. Sayler and Officer Michael J. Luciano wrote to Mary Simon: “There is little we can say which might assuage your grief, but we do want you to know that you have our heartfelt sympathy.”

After Simon’s death, the New School Bulletin published his “Letter to a Judge” in which he presented at his trial. Simon wrote:

“So resistance, to be effective and consistent would have to be open, and its aims should be made clear—in reality, we [The Resisters] functioned as a small articulate pressure group to accept the consequences of actions was consistent with the most democratic form of a truly open society. I don’t give a damn what the Supreme Court considers symbolic speech to be. I know we were speaking with our whole lives to the American people and saying…do you want this war?—do you want to include us in the price?

As an adherent of democracy, I was extremely pessimistic about the response, but it seems that we have played a minor, yet persistent and recognizable part in the growing repudiation of both this war and future imperialistic adventures. At the least, among the students, we have helped to generate disgust with the self-righteous middle-class nationalist that is an essential aspect of modern ongoing Imperial systems. In a society where all careers have become instruments of imperialism, we have at least tried to talk concretely and specifically about the relationship of politics to work.

But although America may be on the verge of chaos, we are in no sense in some kind of revolutionary situation and we have to speak from the best elements of our own traditions of resistance, and to try to live as if democracy was not simply a value free process of measuring opposing forces but an efficacious means of human transformation, a process of movement towards a new reality rather than a code word for universal law and order requiring the massacre of inferior peoples.

But our victims in Vietnam and the possibility of creating a free space for my own work had an undeniable claim on my life. I regret what America has come to mean but in no way regret our attempt to reconstruct another America. Breaking the law is a serious and tragic affair but our price (and insecurity and fear) and our commitment to this struggle for the duration is serious as well. And we have our precedents as does the law. Our conduct will extend them into the future as a resource for others.”

Sincerely yours,

Robert A. Simon

New School Bulletin, November 30, 1969

All materials referenced in this article can be found in the Robert Allen Simon Papers (P-518).