What the AJHS collections can teach us about pandemic and disease

Editor’s Note: Today, September 14, 2022, World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus told reporters that the end of the COVID-19 pandemic is “in sight.” In response to this announcement, we’re happy to share this blog post by Senior Archivist Tanya Elder, all about what the AJHS Collections can teach us about the histories of pandemics, and disease. Originally posted May 20, 2020.

The COVID-19 pandemic has very sharply and abruptly altered the way we live our lives, and many are struggling to imagine what the future will look like. Hearing words and phrases such as “unprecedented” and “not in our lifetime” from leaders, doctors, and even our own family members can contribute to feelings of unease and discouragement. And while it is certainly true that an event like this hasn’t happened during the life of anyone on staff at the American Jewish Historical Society, our collections show that pieces of this narrative we are living have historical precedents.

As an archivist, I often think of items in our collections that relate to the present. A recent search of our digital archive led me to discover a medical crisis of yellow fever resulting in political turmoil, religious leaders working to support their congregations though cholera epidemics, personal human sacrifice for the good of the community in the form of traveling nurses, and the marvel of scientific research and modern medicine in the development of antibiotics. By exploring these sources further, we can see pieces of our current moment and have hope for our future.

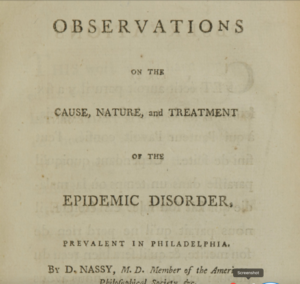

Dr. David de Isaac Cohen-Nassy, a Jewish physician and slaveholder, of Surinamese Dutch-descent, had fled Suriname due to religious freedom issues, and landed in Philadelphia as an outbreak of yellow fever was ravaging the city. Nassy was the first Jewish doctor in Philadelphia, and his treatise, Observations on the Cause, Nature, and Treatment of the Epidemic Disorder Prevalent in Philadelphia (1793), went head-to-head with the famous Pennsylvania physician and Declaration of Independence signatory, Benjamin Rush, and the “contagionist” versus “localist” approaches to the epidemic, which crisscrossed between Boston, New York, and Philadelphia until 1805.

According to the 2012 dissertation, “Feverish Bodies, Enlightened Minds: Yellow Fever and Common-Sense National Philosophy in the Early American Republic, 1793-1805” by Thomas Apel, the struggle in Philadelphia came down to what Apel terms as the “contagionist” versus the “miasmatist/localist” factions of physicians, who had two very different ideas about the fever which continuous spread between the three East Coast shipping outposts:

“…despite the broad similarity of the investigators, from the very beginning, the study of the disease was riven with controversy and conflict, for researchers could not agree on the cause of yellow fever. Yellow fever did not resemble the other epidemic diseases with which Americans had grown familiar. It exhibited odd behaviors that baffled those who tried to understand it. The disease prevailed only in the confines of populous cities. It raged only in the hot and wet periods of summer and autumn, and it struck with apparent discrimination—it afflicted some with particular severity, while others escaped almost entirely. The students of yellow fever immediately split into two schools of thought respecting the origin of the distemper. One group, the ‘contagionists,’ held that it was a contagious disease and that Americans had imported it from the West Indies. The disease did prevail in the Caribbean and the appearance of yellow fever in American cities was always preceded by the arrival of infected ships. As a corrective, contagionists advocated stern quarantine regulations, which would cut off the avenues through which yellow fever infiltrated the sea ports. For the other group, the ‘miasmatists’ or ‘localists,’ the environmental specificity of the illness proved too compelling—they proposed, to the contrary, that yellow fever grew out of local, or domestic sources, and that people could only catch the disease from exposure to those sources. They pushed for sanitation laws and encouraged greater environmental vigilance.”

The two groups were at odds regarding the nature of yellow fever, how it manifested, how to detect it, how to cure it; primarily disease theory versus disease facts. In 1793, Nassy went up against Rush, the leading doctor of his day, in regard to theories of disease importation and quarantine; he also publicly disagreed with Rush over such issues of bleeding patients, and mercury-based calomel.

Apel continued: “By seeking the facts, the investigators hoped also to avoid the pitfalls of theory—deceptive and dangerous notions, devoid of factual basis, which frequently led inquiring minds astray. In his ‘Observations on the Cause, Nature, and Treatment of the Epidemic Disorder,’ for example, the localist … Nassy of Philadelphia asserted that he reached his own conclusions without the undue influence of theory. ‘What I am to advance,’ he wrote, ‘shall be less founded on theory, which often deceives, than on practice, and my clinical observations. Thus I will only say what I have seen, or believe myself to have seen.'”

Nassy’s treatise, which can be read at the National Library of Medicine at the Institutes of Health, concentrated on the facts at hand: what he observed in the patient, how their illness began, and what measures he undertook to treat his patients. Nassy’s first paragraph, to the untrained eye, could be a description of today’s pandemic:

Physicians have published in the newspapers of this country, their methods of preventing and curing this disease, which may be ranked as one of the most destructive and fatal; but none of them have yet thought of favoring the public with an accurate account of the nature, and particularly symptoms of the fever, that makes such cruel havoc.

Never agreeing among themselves, they have mutually opposed the opinions of each other, and have often bestowed reciprocal offense. The result of this difference of ideas, always dangerous for suffering humanity, has been, that each prescribed according to his own manner, as well as preserving persons against the contagion, as for treating the disease, by bleeding, draftic purges, by stimulants, by diluents, by demulcents, by antiseptics, and by tonics, without pointing out in the smallest degree, the circumstances or particular causes, wherein such medicines might be employed or rejected.

The most credulous amongst the people, alarmed by the public papers, and by the numerous precautions advised to be taken against the pretended pestilence, and in order to avoid imaginary evils, produced real ones; some by having recourse to the heating regimen, gave additional fire to their disease and thus created their own graves—other applied to physicians, who, smitten with fear, thought that they perceived pestilential appearances in a common disorder, and ordered medicines, which could only add to the evil. Of consequence, those who did not fall a sacrifice, recovered with difficulty. Hence the number of the sick and dead have amazingly increased and the sentiment of fear operating upon every mind, has made the greatest part of the inhabitants to leave the city, and forsake it, without attendance or assistance the sick, who were not able to quit it.

Would to God that instead of that fear carried to excess, the citizens of Philadelphia had imitated the Turks! thus behaving like them towards those, would not have abandoned their children, nor the children their parents, the servants their masters, nor friends each other; but everyone would have contributed comfort and solace one another. The physicians were compelled by the motives of humanity, to become nurses to the sick, who were then unable of themselves to take medicines.

It was not until the late 19th century that the suggestion of mosquitos (briefly mentioned in Rush’s medical notes, also viewable at the National Library of Medicine) would be offered in regard to the transmission of yellow fever, and not until 1951 that a vaccine would be developed. This period of yellow fever ravaged America and caused much physical, political, and financial consternation as cities were felled by continuous hot spots for twelve years with no full understanding of how yellow fever was transmitted. This calls to mind the saying frequently attributed to Mark Twain: “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”