Judah P. Benjamin’s life was rife with both scandal and success. He was an anomaly: both a lawyer, nicknamed the “Brains of the Confederacy,” who became a respected political leader in the South and a Jewish scapegoat for both the South’s and the North’s shortcomings.

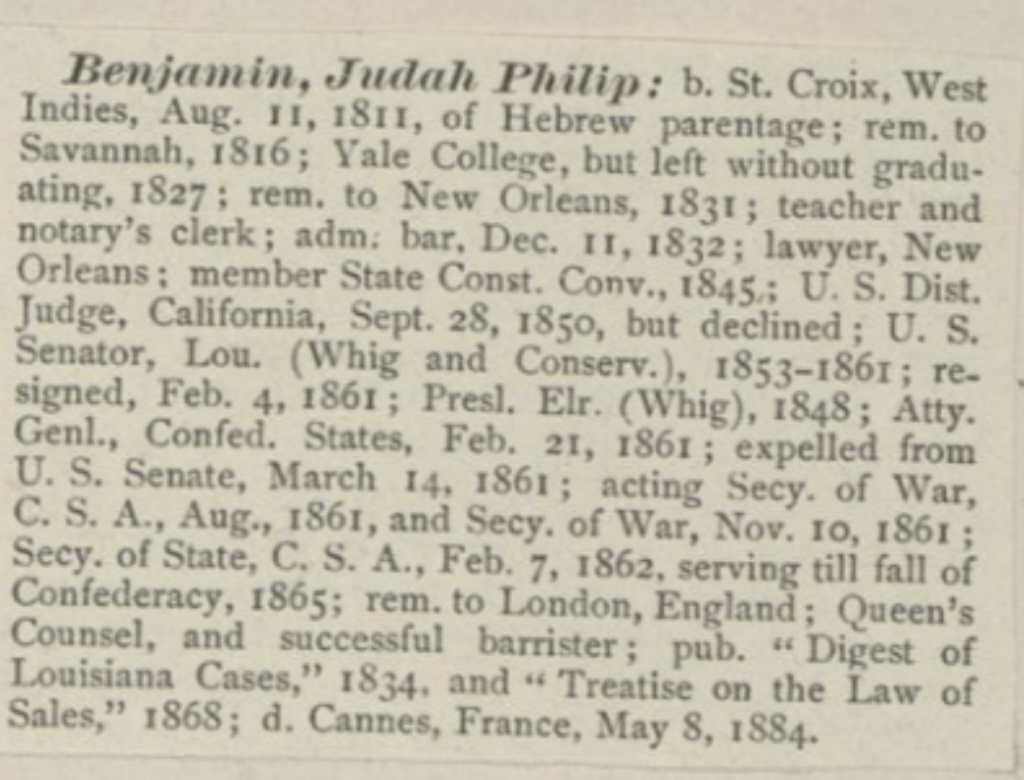

Born to devout Jewish parents in the West Indies in 1811, Benjamin spent his childhood in South Carolina. He was exceptionally intelligent, attending Yale Law School at the age of 14. He was soon expelled, either for theft or gambling, and moved to New Orleans, where he continued his studies and eventually passed the bar exam and became a lawyer at the age of 21.

While in New Orleans, he met Natalie Bauché, the youngest daughter of a family of wealthy French-Creole socialites. The pair were soon married at the insistence of Bauché’s parents, who were happy to see their scandalous daughter wed. Their marriage was unsuccessful, and Bauché moved permanently to Paris shortly after their daughter was born, leaving Benjamin alone in America. He tried many times to save the marriage but ended up living apart and visiting them once a year.

Despite a tumultuous personal life, Benjamin found success as a lawyer. One of his most interesting cases was that of a group of enslaved people who had revolted while aboard a ship transporting them to New Orleans in 1834. They rerouted it to the Bahamas, which were part of a newly emancipated Britain, making them legally freemen the second they stepped foot on land. Their former enslavers sued the insurers of the ship for allowing this to happen and losing their capital. Benjamin argued on the side of the insurers and won, partly thanks to a strikingly abolitionist argument: “What is a slave? He is a human being. He has feelings and passion and intellect. His heart, like the heart of the white man, swells with love, burns with jealousy, aches with sorrow, pines under restraint and discomfort, boils with revenge, and ever cherishes the desire for liberty…”

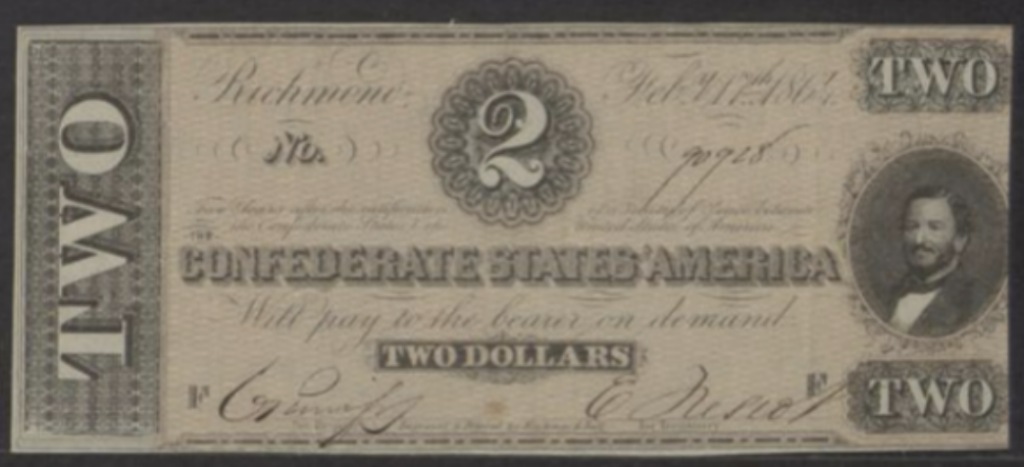

Benjamin was still serving in the Senate when the South began to consider secession in the early 1860s. In a resignation speech considered one of the best in American history, he resigned in 1861 to serve the Confederacy. He became the first Jew (who had not renounced their faith) to hold a Cabinet position in American government when Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederacy, appointed Benjamin as his Attorney General that same year. Benjamin served multiple roles within the Confederate government, including Secretary of State.

Benjamin became Davis’s right-hand man, serving at high-level government positions throughout the Civil War. Even with his brilliance and high-ranking position, Benjamin faced relentless antisemitism and was often presented as the catalyst of the South’s failures. To make matters worse, Benjamin was exceptionally loyal to Davis, even when it was to his detriment. In 1862, Benjamin agreed to take the fall for Davis after the president allowed Roanoke Island in South Carolina to be taken by the Union. The two decided that blaming it on Benjamin would distract from the fact that the South had an arms shortage. This was the biggest military blow to the South – so tragic that Benjamin’s reputation was forever damaged by it. Critics labeled Benjamin as Davis’s “pet Jew” and called out his apparent lack of a backbone. Years later, in 1936, the grandson of one of the Confederate generals who fought for Roanoke Island was asked about the loss. He blamed it on “the fat Jew sitting at his desk.”

Benjamin was forced to resign from the Cabinet but was appointed Secretary of State by Davis soon after. There was a vote to overturn the reinstatement, but because few in the South felt comfortable with criticizing Davis, it failed. The major newspapers were silent on the whole situation, being both too afraid to disagree with Davis’s decision and too angry to show Benjamin in a positive light.

In 1864, Benjamin was met with even more criticism after he made a shocking speech to the Senate that called upon the South to “arm their slaves” and proposed to allow emancipation to any slaves who volunteered to serve in the Confederate armies. Though Benjamin had initially opposed this suggestion, he put it forward to enable the South to avoid defeat. His proposal, which would have gone against the Confederacy’s view of slavery, was met with indignation and was instantly shut down.

Because the Confederacy would not consider this proposal, their military situation became dire. For a short time, Davis and his cabinet, including Benjamin, were forced to travel across the South, evading Northern capture as the Confederacy lost more and more land. Benjamin retained his good humor the entire time, singing a song of his own making called “The Exit from Shocko Hill.”

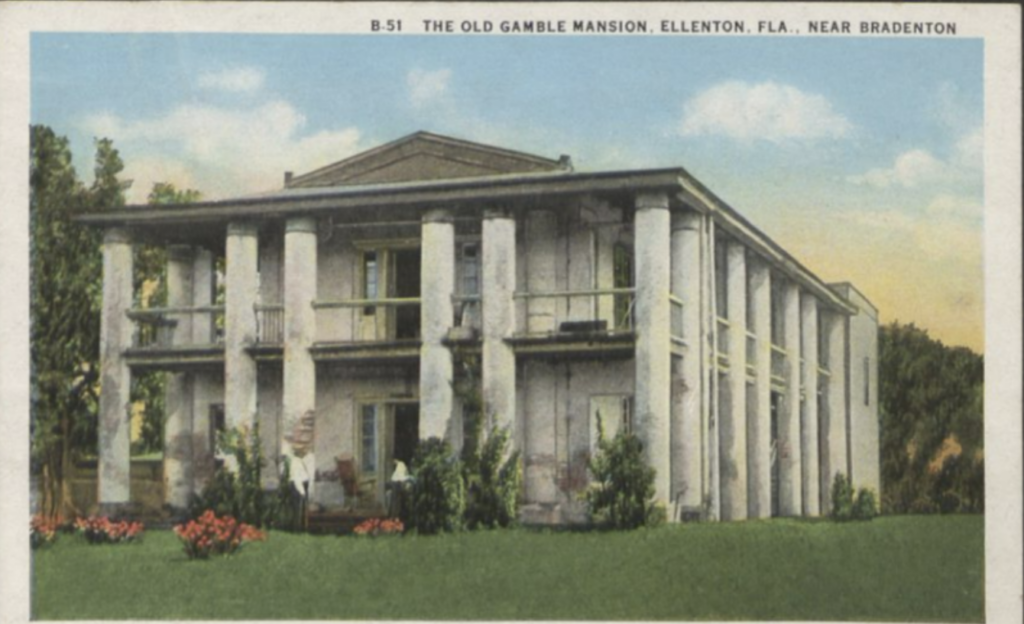

Benjamin’s time in America ended with the fall of the Confederacy. Besides being a high-ranking Confederate official, Benjamin was also blamed for President Lincoln’s assassination in 1865. He hid for a short time in Gamble Mansion in Florida, before fleeting to England, also in 1865. During the dangerous journey, he had to disguise himself multiple times to avoid Northern capture. A few of these personas included a Frenchman who spoke no English and a Jewish cook on a ship. One ship he travelled on exploded, forcing him and three others to extinguish the flames and return to their starting point in the Bahamas.

Benjamin reached England safely in 1865. He lived the rest of his life as a successful lawyer in England, getting appointed to the Queen’s Counsel in 1872, the highest rank for jurists. He died in 1884 under the name Philippe Benjamin in Paris. In one last insult, Bauché had priests administer the last rites of the Catholic Church to Benjamin before his death.

Benjamin’s life as a high-ranking Confederate Jew was remarkable. His Judaism became an excuse for condemnation from both sides. He was blamed for the South’s failures by the Confederacy and for the South’s victory by the Union. He owned slaves, despite this being antithetical to his Judaism, which he held dear. He served loyally as Davis’s right-hand man, possibly because Davis knew there was no threat of a Jew overthrowing him as President of the Confederacy.

Benjamin never tried to hide or downplay his Jewishness. In one Senate hearing, a senator from Ohio attacked Benjamin for his stance on slavery, calling him an “Israelite in Egyptian clothing.” Benjamin replied: “It is true that I am a Jew, and when my ancestors were receiving their Ten Commandments from the immediate Deity, amidst the thundering and lightnings of Mt. Sinai, the ancestors of my opponent were herding swine in the forests of Great Britain.”