In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, American Jews commissioned and displayed portraits in a range of media, from oil paintings on canvas to the less familiar formats of ivory miniatures and paper silhouettes. Although diminutive, miniatures and silhouettes are emotionally potent and reward close examination. What exactly are they, and how were they created?

Miniatures:

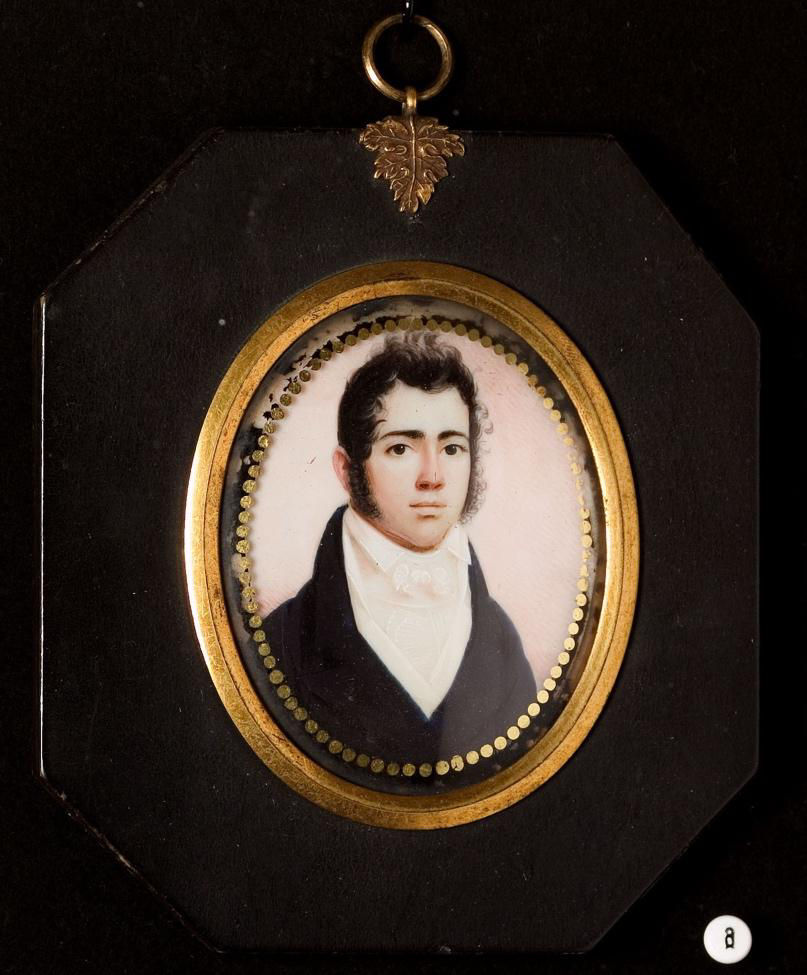

Unlike oil paintings, miniatures are portable. Small enough to fit within the palm of one’s hand, they could be kept in a pocket or worn as jewelry.

During this period, most artists painted portrait miniatures by applying watercolor to a thin slice of ivory. The ivory could be mounted on a piece of thick paper or card. Once complete, the excess paper or card was cut, and the portrait could be kept in decorative or functional housing and protected under glass. The reverse sometimes included the subject’s hair arranged in an intricate pattern.1

The collection of the American Jewish Historical Society includes miniatures of siblings Sarah Brandon Moses and Isaac Lopez Brandon (Figures 1 and 2). Sarah and Isaac were born to a Jewish father and an enslaved mother in Barbados.2 Through marriages to members of the Moses family of New York, both siblings entered the upper echelons of Jewish society.3 These portraits record Jews of African descent, attesting to the complexity of Jewish identity and the mobility of Jewish people.

Silhouettes:

The collection of the AJHS includes numerous portraits by Auguste Edouart, a famed French-born silhouette cutter who worked itinerantly in the United States between 1839 and 1849. As a medium, silhouettes possessed various advantages: they were more affordable and quicker to complete than painted portraits.4

Edouart advertised his services in the New York Herald, informing readers that a full-length portrait of a seated subject cost $1.75, while one of a standing subject was $1.25. He charged 87 ½ cents for silhouettes of children and 62 ½ cents for bust-length portraits.5 In comparison, Edouart’s contemporary Thomas Sully charged $600 for a full-length painted portrait and $100 for a bust-length portrait.6

Handwritten inscriptions on many of Edouart’s silhouettes identify his sitters by name, as well as the date and location of the work’s creation. For example, he created this work (Figure 3) in New York on April 6th, 1840, and he identifies his subjects as (from left to right) Rebecca Moses, Fanny Asher, and Hyam Asher. Edouart articulates minute details, such as eyelashes and individual curls, with precision and care.

Uniquely, Edouart depicts Rebecca Moses at work cutting a silhouette of her own, although the likeness that she holds is bust-length rather than full-length. Rebecca could have cut and assembled silhouettes of her loved ones in a commonplace book or album.

Edouart’s backgrounds vary. He sometimes affixed the silhouettes to blank paper, while at other times, he employed a type of print called a lithograph to provide a setting for his subjects (Figure 4).

Ultimately, portrait miniatures and silhouettes provide generative points of entry into Jewish history and culture, offering insight regarding how American Jews saw themselves and how they wanted others to see them.

__________________________________

- Robin Jaffee Frank, “Introduction,” in Love and Loss: American Portrait and Mourning Miniatures (New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery, 2000), 1-13. ↩︎

- Laura Arnold Leibman, “Portraits in Ivory,” in The Art of the Jewish Family: A History of Women in Early New York in Five Objects (New York: Bard Graduate Center, 2020), 100. ↩︎

- Ibid., 126-28. ↩︎

- Penley Knipe, “Shades of Black and White: American Portrait Silhouettes,” in Black Out: Silhouettes Then and Now, Asma Naeem, Penley Knipe, Alexander Nemerov, Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, and Anne Verplanck (Washington: National Portrait Gallery, 2018), 79. ↩︎

- Auguste Edouart, “Silhouette Likenesses,” New York Herald, September 16, 1840. ↩︎

- Thomas Sully, “Charges for Portraits,” February 27, 1830, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; transfer from the National Museum of American History; gift of Harriet W. Nutting. https://www.si.edu/object/thomas-sullys-price-list:npg_AD_NPG.74.26. ↩︎

For more on this topic please enjoy Live from the Archives: Family Portraits and Multiracial Identity with Laura Arnold Leibman and Annie Polland.