Rebecca Naomi Jones: The Wreckage is made possible by funding from the Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided through the American Jewish Education Program, generously supported by Sid and Ruth Lapidus.

Archival Audio, Eric Johnston: “We will forthwith discharge or suspend without compensation, those in our employ and we will not re-employee any of the Ten until such time as he is acquitted or has purged himself of contempt and declares under oath that he is not a Communist. We will not knowingly employ a Communist or a member of any party or group which advocates the overthrow of the government of the United States by force or by any illegal or unconstitutional methods. We request Congress to enact legislation to assist American industry to rid itself of subversive disloyal elements. Nothing subversive or un-American has appeared on the screen; nor can any number of Hollywood investigations obscure the patriotic services of 30,000 loyal Americans in Hollywood who have rendered their government invaluable service in war and in peace.”

Rebecca Naomi Jones: On November 24, 1947, ten Hollywood writers and directors were cited for contempt of court for their refusal to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Criminal charges were issued against the group that would become known as “the Hollywood Ten,” and the first systematic Hollywood blacklist had begun. Of the ten – Alvah Bessie, Herbert J. Biberman, Ring Lardner Jr, Lester Cole, Edward Dmytryk, John Howard Lawson, Albert Maltz, Samuel Ornitz, Adrian Scott, and Dalton Trumbo – six were Jewish, as were many of the studio executives who voted to blacklist them.

From the American Jewish Historical Society, this is The Wreckage: American Subversives. I’m your host, Rebecca Naomi Jones. Welcome to the trial of The Hollywood Ten. Our story begins in wartime Hollywood.

Archival Audio, Newsreel: [Music]

Hollywood’s most famous movie stars leave the film Capital to help the government sell war bonds. Irene Dunn, Ronald Coleman, Hedy Lamar, are all part of a contingent of some 50 screen celebrities giving their time and talents to aid the national war effort. The country has asked the people to invest a billion dollars in one month to help pay for the war. And here’s the

start of the drive! Boarding a special train for Washington, they’ll tour 300 cities from coast to coast, go to any city that agrees to subscribe at least $1 million.

[Music]

Yes, in Democratic America, everybody is doing his bit. There goes Jimmy Stewart on his way to enlist one of the most popular stars on the screen joining the Air Force as a private. Jimmy has now won promotion, today he’s Lieutenant Stewart, USA!

[Music]

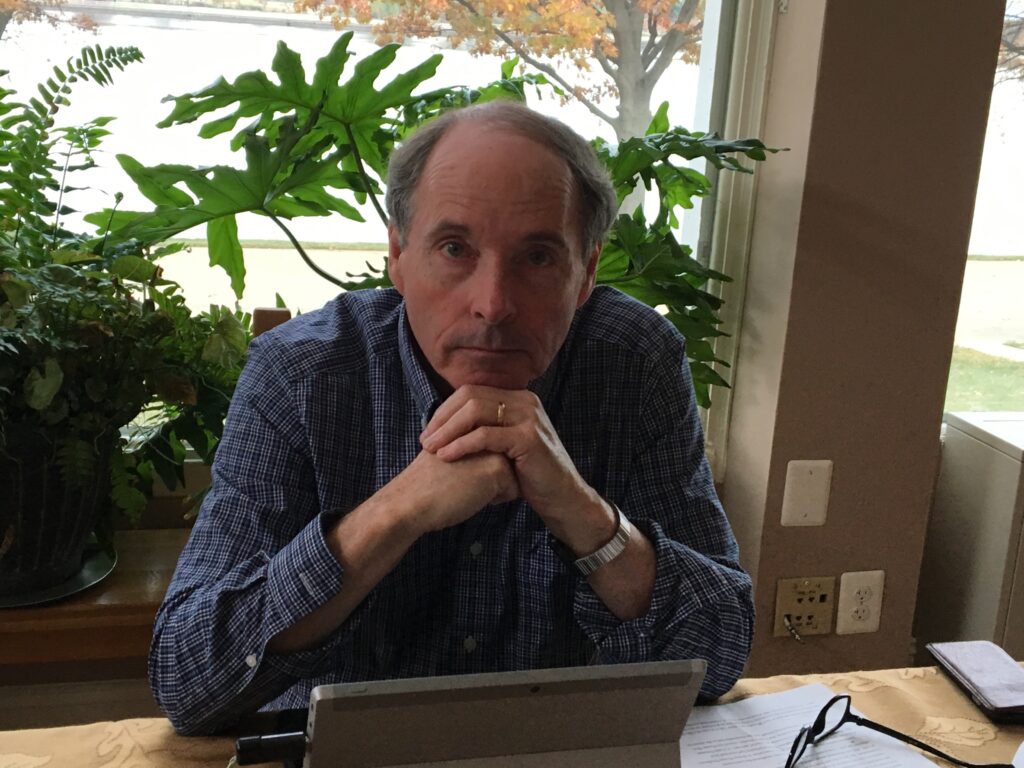

Rebecca Naomi Jones: Joining us once again is Dr. Thomas Doherty, professor of American Studies at Brandeis University and author of Show Trial: Hollywood, HUAC, and the Birth of the Blacklist.

Dr. Thomas Doherty: Prior to the Second World War, Hollywood always configured itself as—and I think most moviegoers thought of it as—an entertainment machine. So in the 1930s, you went to the movies to see Fred and Ginger dance in Art Deco apartments and to escape the woes of your normal life.

During the Second World War, however, Hollywood was marshaled by the government—and by itself; it didn’t need to be coerced into doing this—as not just an overt entertainment machine, but as a propaganda machine, something—an industry whose images taught us the values and the skills necessary to fight the Second World War. And so throughout the industry, in every genre, whether it was a straight documentary or cartoons or feature films, we were given lessons that would make us better soldiers, either in the battlefield or on the home front, to fight the Nazis. So we were given an education in ideology. And especially, we kind of wanted to recapture our best sense of ourselves in terms of our traditional aspirations for tolerance and for teamwork. So throughout the Second World War, virtually every film you saw, even some that seem just zanily escapist, taught some kind of lesson.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: The entertainment industry mobilized quickly. In addition to morale-boosting USO shows, actors appeared in PSA’s to promote aid organizations and war bonds drives, and even encouraged Americans to plant Victory Gardens in their neighborhoods, at a time when food rationing meant that many cabinet staples were in short supply.

Studios like Paramount, MGM, Fox, Warner Brothers, and RKO Pictures worked with the Office of War Information and the Bureau of Motion Pictures, and used their extensive resources and cinematic heft to create propaganda and training films that were shown in movie theaters, on military bases, and in homes. Directors like Frank Capra, George Stevens, John Ford, and John Huston helmed some of these major productions, and put their careers on hold in support of the war effort.

Dr. Thomas Doherty: So the consequence is that coming out of World War II, Hollywood, Washington, and the average moviegoer knew that movies just weren’t a harmless diversion but movies were a transmission belt, and a very powerful transmission belt, for ideas and ideology. And that’s one thing, I think, in fairness, the House Un-American Activities gets right in 1947 when they call Hollywood to Washington to defend itself against charges of communist subversion, both in kind of union activities and on the motion picture screen. One thing HUAC gets right is that movies matter.

Archival Audio, newsreel: Calling the House Un-American Activities Committee to order, Chairman J. Parnell Thomas of New Jersey opens an inquiry into possible communist penetration of the Hollywood film industry. The committee is seeking to determine if Red party members have reached the screen with subversives. Lists of prominent motion picture witnesses appear before the committee. Speaking for the films, Eric Johnston, president of the Motion Picture Association, talks frankly concerning the attitude of the producers.

“We’re accused of having communists and communist sympathizers in our employ. Undoubtedly there are such persons in Hollywood as you will find elsewhere in America, but we neither shield nor defend them. We want them exposed. We’re not responsible for the political or economic ideas of any individual, but we are responsible for what goes on the screen. We guard that with great care. If communists have attempted to inject their propaganda into the motion picture, they have failed miserably. We will never permit them to succeed.”

Rebecca Naomi Jones: By the end of 1945, the spirit of togetherness and sacrifice the war effort brought was fading – and rapidly. During World War II, President Roosevelt had negotiated a no-strike pledge with major unions that included the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations. But after the war, many of the same labor issues remained unaddressed, and the United States experienced a massive strike wave across nearly every industry. More than 5 million Americans participated in labor stoppages.

The motion picture industry was no exception. Union actions coupled with the high profile nature of the industry made it a prime target for HUAC.

Dr. Thomas Doherty: The entertainment industry is targeted for two reasons. First, the Second World War has taught us movies matter. We all know that. That is something that people might not have known as powerfully in the 1930s. The war has taught us this, whether it’s the films of Frank Capra for the US Army, or Leni Riefenstahl for the Nazis, or all those great entertainment films that teach us the values we need to fight the Second World War.

And the second reason, of course, is Hollywood is publicity. So if you go after a teacher’s union, there aren’t going to be platoons of newsreel cameramen photographing these fourth-grade teachers marching into the Capitol to be interrogated. So that’s the other reason, frankly. If you’re inviting Gary Cooper or Walt Disney—or subpoena them—to come into a congressional hearing room, they’re going to get the kind of motion picture coverage and publicity coverage that smaller fry are not going to get.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: Among the groups targeted, American Jews, many of whom were active in the labor movement, entertainment, and other industries that were deemed suspicious, were disproportionately affected.

Dr. Thomas Doherty: The Jewish angle is really interesting on this because you can read it two ways. You could read it as an expression of antisemitism – or not. And maybe the best way to get at this question is to talk about a guy who is rightly forgotten today but very influential at the time, a guy named John Rankin, who was a congressman from Mississippi, and he was a vicious racist and antisemite and very influential on the House Un-American Activities Committee. In fact, it was Rankin’s parliamentary maneuvering that made the committee a standing committee, meaning that it didn’t need—it got automatic authorization. And he’s a Democrat from Mississippi.

And in ‘46, the Republicans take over. And the guy chairing the committee who holds those infamous hearings in October 1947 was a guy from New Jersey, a Republican named J. Parnell Thomas. Thomas was smart enough to know that he did not want John Rankin on the dais during these committee hearings because Rankin was such a notorious antisemite that it would discredit the agenda of the committee, which he did not want to be smeared with the brush of being antisemitic. And he lucked out because what happens is another Mississippi politician who was probably the only competitor Rankin had for antisemitism, a guy named Theodore Bilbo, which is this senator with this classic name, dies in office, and Rankin goes down to Mississippi to campaign for his Senate seat. And when he leaves Washington, that’s when J. Parnell Thomas is smart enough to have the committee hearings in late October, knowing that Rankin will not be there.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: The Hollywood Ten – originally nicknamed the Hollywood Nineteen, or the Unfriendly Nineteen, were screenwriters, producers, directors, and actors who were called before HUAC, asked to answer for what the committee deemed “subversive behavior.”

Dr. Thomas Doherty: And their behavior was very left wing and, in some cases, communistic. So they were called by the committee in order to explain themselves. And they were called the Unfriendly Ten, or the Unfriendly Nineteen originally, because they opposed the committee’s agenda.

So, there were two kinds of witnesses that the committee called for their famous investigation. And they were, on the one hand, the friendly witnesses. And they were people like Jack Warner and Gary Cooper, Leo McCarey, Louis B. Mayer—some of the famous moguls and directors who, although they did not feel that Hollywood was a hotbed of communism and that the charge that Hollywood was a hotbed of communism was unjustified, were largely sympathetic to the committee’s desire to root out communist influences, and so they came willingly. Even though they were subpoenaed, they came willingly to testify before the committee.

And there were a group of other witnesses who opposed the committee’s agenda, and they were subpoenaed and came unwillingly. They were called the unfriendlies. Now, out of the unfriendlies, ten of them were called before the committee and defied the committee, refused to answer the famous question of the time—and this was known, at the time, as the sixty-four-dollar question in the pre-inflationary money—are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?

Archival Audio, John Howard Lawson’s HUAC Testimony:

Parnell Thomas: The question is have you ever been a member of the communist party?

John Howard Lawson: I am framing my answer in the only way in which any American citizen can frame his –

Thomas: Then you denied questions –

Lawson: Absolutely invasive –

Thomas: Then you deny, do you you refuse to answer that question is that correct-

Lawson: I have told you that I will, all over my beliefs my affiliations with good health with the American public and they will know where I stand, as they do from what i have with –

Thomas: Stand away from the stand!

Lawson: This name for Americanism for many years and I should –

Thomas: Stand away from the stand!

Lawson: For the bill of rights without sending –

Thomas: Stand away from the stand!!

Rebecca Naomi Jones: John Howard Lawson, a prolific screenwriter who helped organize the Screenwriters Guild and served as its first president, was yanked from the chamber for refusing to answer about his alleged Communist ties.

Born in 1894 in New York City to an upper middle class Jewish family, Lawson was exposed to societal issues from a young age thanks to his mother Belle’s activism. His father, Simeon, changed the family’s surname from Levy to Lawson in the late 1880s, to shield them from waves of antisemitism that permeated across the world, their home in New York no exception.

When Lawson matriculated at Williams College in 1910, his Jewish background became the subject of controversy among his classmates, and in one incident, he was denied entry to the Williams College Monthly’s editorial board because some students raised concerns over his Jewish background. This experience was formative, and he carried it with him through the years, and struggled with his Jewish identity as he became more involved in theater, motion pictures, and labor organizing. He joined the American Communist Party in 1934.

Lawson testified before HUAC on October 29, 1947, and alongside the other nine “unfriendlies,” refused to comply with the proceedings.

Dr. Thomas Doherty: Now, this group made the mistake of standing not on its Fifth Amendment rights, which was you didn’t have to incriminate yourself, but on their First Amendment rights of free expression because this group of people wanted to argue with the committee and come back and answer their charges. And so what they end up doing is kind of filibustering. They don’t answer the question. They try to read statements. They basically engage in this angry, vitriolic rhetoric. And because of that, they’re held in contempt of Congress, and ten of them are ultimately charged, and they go to jail anywhere from a year to six months.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: The sentencing sent shockwaves throughout the entertainment industry, but it was not the only consequence of non-compliance with the proceedings. On November 25, 1947, just one day after the sentencing, the Association of Motion Picture Producers suspended the Ten, and publicly pledged that quote “thereafter, no Communists or subversives would knowingly be employed in Hollywood” unquote.

Dr. Thomas Doherty: The blacklist comes about because of the HUAC hearings in October 1947. And what happens is, the next month, the Motion Picture Association of America calls the studio heads together for a conclave at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York. And the moguls all get together and decide that this is terrible publicity for the industry, and that they agree, as a group, to not knowingly employ a member or somebody suspected of being a member of the Communist Party.

And the first people that are blacklisted, of course, are the Hollywood Ten because they have been on record as saying they will not say whether they’re a communist or not. So all those guys get immediately fired. And forever after, at least until 1960, if you’re a motion picture employee, particularly an actor, a director, a screenwriter, you have to attest to your American bona fides by saying that you are not a communist. And if you don’t say that, if you refuse to answer the sixty-four-dollar question, you will be blacklisted. And that means you will be unemployable in the motion picture industry. And this destroys or sidetracks hundreds of careers in the next twelve or fifteen years.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: The list grew rapidly, and on June 22, 1950, anti-Communist business leaders joined forces and published Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television. Inside were the names of 151 so-called “Red fascists and their sympathizers.”

Ultimately, the HUAC proceedings failed to uncover any proof that there were Communist spies or sympathizers who had infiltrated Hollywood and were secretly disseminating propaganda, but for many who were blacklisted, the damage to their careers had been done. Many on the list never worked again; others lived in exile and continued their careers abroad.

John Howard Lawson remained banned from working in Hollywood, though he continued to write non-theatrical works or under pseudonyms, including co-writing the anti-Apartheid film Cry, the Beloved Country, with teaching stints at several universities. He passed away in 1977, and while some of the Ten were forgiven and welcomed back into the industry, Lawson never worked in Hollywood again.

Dr. Thomas Doherty: So it’s really this terrible passage in entertainment history. And I think it sort of always has had this legacy. So even people who have never experienced the blacklist will often evoke it, even today in Hollywood, as sort of the worst passage in Hollywood history. The thing about the official blacklist, as it were, is it was actually a public statement by the MPAA—a statement, by the way, they have never rejected. They have never kind of gone back and regretted that. And it was enforced by Congress—and by the FBI, so you had executive branch power also encouraging this allegedly private arrangement where the studios wouldn’t hire certain people.

Archival Audio, The Hollywood Ten film (1950): When we were asked, are you now, or ever been a member of the Communist Party, the committee was really preparing to ask you, “Are you now or have you ever been in favor of peace?” Who is loyal to this land? Those who want to settle world problems with the hydrogen bomb? We feel that the question of peace and war, of devastated cities of millions of dead Americans, is too important to be left to the generals or in the hands of the Committee on American activities. In 1859, Abraham Lincoln said “But people are the rightful masters of the Congresses and the courts.” We believe this, and for asserting that belief before a congressional committee, ten of us are going to prison, casualties of the Cold War. How many more will there be? There need be no more. That depends on you. Truly, it depends on you.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: From the American Jewish Historical Society, I’m Rebecca Naomi Jones. This episode was written by executive director Gemma R. Birnbaum. Recording, sound design, and mixing were done at Sound Lounge. Transcription is provided by Adept Word Management. Archival material is courtesy of the collections of the American Jewish Historical Society, the US National Archives, and the British Movietone Archive via AP Newsroom.

For episode transcripts, additional resources, and links to the collections featured in this episode, visit ajhs.org/podcasts. If you enjoyed this episode, please rate and review us on your preferred podcast platform which helps others discover our series.