Rebecca Naomi Jones: The Wreckage is made possible by funding from the Ford Foundation.

Additional funding is provided through the American Jewish Education Program, generously supported by Sid and Ruth Lapidus.

Archival Audio – Edward R. Murrow’s No Fear Editorial: Earlier, the Senator asked, upon what meat does this our Caesar feed? Had he looked three lines earlier in Shakespeare’s Caesar, he would have found this line, which is not altogether inappropriate. The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves. No one familiar with the history of his country can deny that congressional committees are useful.

It is necessary to investigate before legislating. But the line between investigating and persecuting is a very fine one, and the junior senator from Wisconsin has stepped over it repeatedly. His primary achievement has been in confusing the public mind as between the internal and the external threats of communism.

We must not confuse dissent with disloyalty. We must remember always that accusation is not proof, and that conviction depends upon evidence and due process of law. We will not walk in fear, one of another. We will not be driven by fear into an age of unreason if we dig deep in our history and our doctrine.

And remember that we are not descended from fearful men. Not from men who feared to write, to speak, to associate, and to defend causes that were for the moment unpopular. This is no time for men who oppose Senator McCarthy’s methods to keep silent.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: In the spring of 1954, the blustering anticommunist crusader, Senator Joseph McCarthy, set his sights on a new target: the United States Army, alleging Communist infiltration of the Army Signal Corps lab at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey – the same lab where Julius Rosenberg had once worked. In turn, the Army accused McCarthy of using his position to pressure them into giving preferential treatment to his former aide, G. David Schine. The hearings, which were televised live on ABC and the DuMont network, and watched by an estimated 80 million people, unveiled to the nation the true cost of McCarthy’s crusade.

From the American Jewish Historical Society, this is The Wreckage: American Subversives. I’m your host, Rebecca Naomi Jones. Welcome to the televised hearings of The Army. Our story begins with a Nazi war crime.

Archival Audio, Malmedy Massacre 1944: “At Malmedy, the battle recedes. American soldiers gently uncover their comrades. Captured here, more than 100 were massacred. Even unarmed medical troops were shot by enemy cannon and machine gun after their surrender. German prisoners apprehensively watch as the atrocity is uncovered.”

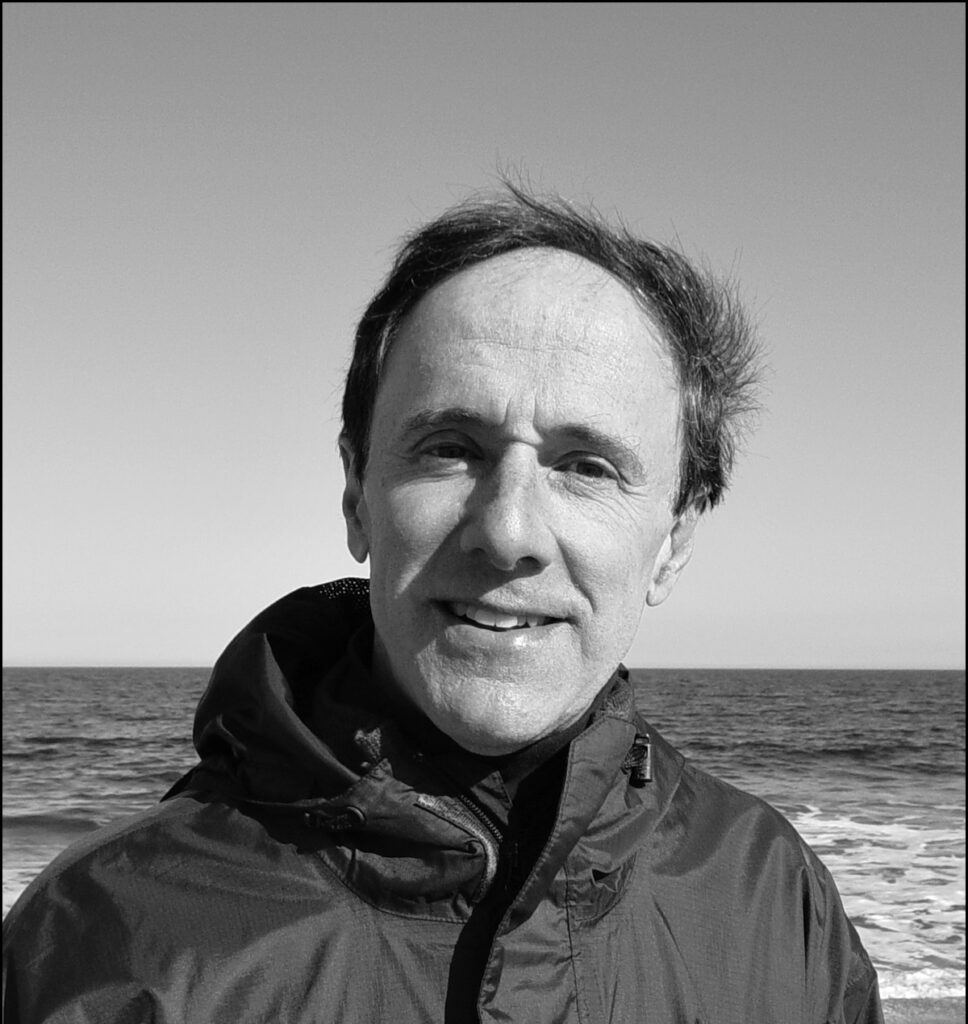

Rebecca Naomi Jones: Joining us is Larry Tye, author of Demagogue: The Life and Long Shadow of Senator Joe McCarthy.

Larry Tye: So, Joe McCarthy was a backbench senator from Wisconsin who was looking for a way to ensure his reelection and to get noticed. And to do that, he started out his career by defending the perpetrators of one of the worst massacres during World War II, the so-called Malmedy Massacre.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: On December 17, 1944, in the earliest days of what would become known as the Battle of the Bulge, German SS and American troops clashed in a brief battle just outside of Malmedy, a small city in German-controlled Belgium.

The SS division, commanded by one of the Nazi’s most brutal military leaders, Joachim Peiper, took more than 150 American soldiers prisoner. It was bitterly cold that winter day, and the American prisoners of war shivered as they were lined up in 8 rows. They were searched and stripped of all personal items, weapons, and medical kits.

Then, without warning, the SS opened fire, and killed more than 80 soldiers, medics, and even a Belgian civilian who witnessed the horror. Some Americans managed to flee or play dead; only approximately 40 survived. The bodies remained frozen in the killing field for more than a month, until war crimes investigators were able to access the site.

On July 16, 1946, a U.S. Army military tribunal convened at Dachau sentenced 46 members of the SS division to death; others received sentences ranging from 10 years to life in a military prison.

In the aftermath of the sentencing, the convicted men claimed that the United States had used torture and other unlawful methods to secure the evidence used to convict them, and that any confessions were coerced. As publicity continued to mount, a commission to investigate was convened. Some death sentences were commuted to life in prison, and 13 convicted SS men were freed.

The controversy did not go away quickly, and in 1949, the U.S. Senate conducted a series of investigative hearings. Seeing a chance at notoriety, McCarthy took a keen interest in the proceedings, and in particular, allegations that the interrogators, some of whom were Jewish, had used their positions to enact revenge. McCarthy, rather than do his job as an observer, instead became an active participant, and aggressively questioned the interrogators and other witnesses, and showed sympathy toward the convicted Nazis.

Larry Tye: And he said that these Nazis who had killed soldiers who were holding up a white flag should see their death sentences lowered, should be potentially freed. And that didn’t work, and the Senate didn’t back him, and the Army repudiated all of his charges.

So then he went after, in order, Jews and gays and anybody that he could find. And he finally found an issue in 1950 that stuck, and that was going after communists and saying that there was one behind every pillar in the State Department and throughout the American government.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: In February of 1950, the Republican Party sent McCarthy to Wheeling, West Virginia to make a Lincoln Day speech at the Women’s Republican Club. His first term as a senator had largely been regarded as a failure, and it was assumed that he would not win the re-election he so desperately wanted. McCarthy was chosen to go to Wheeling because it was a low-priority assignment, and he was quickly becoming known as a likely lame duck.

Larry Tye: When Joe McCarthy showed up at the Lincoln Day Dinner in Wheeling, West Virginia in 1950, he had in his briefcase two speeches. One was a speech talking about housing issues. And if he had reached into the briefcase and delivered that speech that night, we would never have heard any more of Joe McCarthy. And instead, he reached deeper into his briefcase and pulled out a speech that talked about there being a communist just about everywhere in the US State Department.

His charges were front-page news. The defense of the people that he was charging generally ended up, the next day, next to the corset ads in the newspaper. And it was working, and he was getting noticed. And long after the era of the House Un-American Activities Committee, which sort of launched the Red Scare, Joe McCarthy was phase two. And he was front and center, which is where he had always dreamed about being.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: “205 REDS IN THE STATE DEPARTMENT,” shouted the headline in the following day’s Associated Press. As attention on McCarthy and his claims grew, so did fear of communism among the American public. McCarthy’s star began to rise, despite one crucial thing: the list he claimed to have did not exist.

With one lie, McCarthy set off one of the largest inquiries into the U.S. government in the nation’s history, and gave new life to the second American Red Scare.

In the November 1952 election cycle that saw revered World War II General Dwight D. Eisenhower win the presidency, Republicans also gained control of the Senate. McCarthy became Chair of the Senate Committee on Government Operations, and needed to fill key positions in its Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations.

Larry Tye: And he initially considered a guy named Bobby Kennedy, who was a young graduate of the University of Virginia Law School, smack in the middle of his class, was out there looking for a job, and he did what all the Kennedys did when they were looking for a job. He asked Papa Joe, the Joe Kennedy, to help him find a job. Joe Kennedy had given enough money to Joe McCarthy over the years that when Kennedy called McCarthy and said, I need a job for my son Bobby, McCarthy said, Sure.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: McCarthy appointed Kennedy as assistant counsel to the Senate subcommittee to investigate communist subversion, having decided that while Kennedy deserved a job, he wasn’t what was needed for the top job.

For that role, McCarthy hired 26 year old Roy Cohn.

Larry Tye: McCarthy went out looking for a smart young staffer, and had seen what Roy Cohn had done in taking on communists in earlier cases, and decided that Cohn was just the guy for him: smart, young, precocious, and willing to do anything—and I emphasize the word anything—to get where he wanted to be. And that was Joe McCarthy’s kind of guy—even though Roy Cohn was Jewish, and McCarthy had shown early in his career either that he was, again, willing to do anything, which meant appealing to his German constituency, the large number of German voters in Wisconsin, by doing a campaign to rescue Nazi perpetrators of a massacre—but it didn’t matter. And whether or not McCarthy was antisemitic, we will never know. But he took on the Jewish Roy Cohn because it would help him get where he wanted to be, which was on the front pages.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: Cohn, who rose to prominence for his role as a prosecutor during the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg spy trial, was born in the Bronx to mother Dora and father Albert, a New York State Supreme Court judge. After graduating from Columbia Law School at age 20, he worked as a clerk until he was old enough to take the bar exam. Once admitted to the bar, he became an assistant US attorney, and joined the board of the American Jewish League Against Communism.

He and Kennedy began their roles on the subcommittee in early 1953, but after a series of disagreements between the two men, including one particularly heated exchange that escalated into a fist fight, Kennedy left his post. His parting words to McCarthy was that the committee was quote, “headed for disaster.”

Over the next year, McCarthy and Cohn relentlessly pursued their anticommunist agenda, investigating every level of the State Department, and making accusations that there was even subversion within the Eisenhower administration. McCarthy described the nation as quote “engaged in a final, all-out battle between communistic atheism and Christianity.”

Larry Tye: But then he took on an enemy that was too big and too much a part of the American mainstream culture, and that was the U.S. Army.

Archival Audio: In the spring of 1954, the stage is set for the most astonishing spectacle in American political history. A United States Senator and the Department of the Army have leveled charges against one another, ranging from blackmail to treason. In an open hearing, the Senate committee must decide who is right.

This controversy reaches far beyond the committee room, for it involves the careers of statesmen and generals, the prestige of the Senate, and the power of the President.

Two men dominate these hearings. One is Joseph Welch, defense attorney for the Army, a shrewd trial lawyer from Boston. The other is Senator Joseph McCarthy. In less than eight years, he has become perhaps the most powerful man in the Senate. The most controversial figure in America.

Larry Tye: He charged that a base in New Jersey called Fort Monmouth was a nest of the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg-type characters, essentially spies. And he was taking on the secretary of the Army, and he was taking on, most importantly, the president, the war hero president, Dwight Eisenhower who knew that at some point, McCarthy would do himself in. And Eisenhower waited a lot longer than I thought he ought to to confront McCarthy, but when McCarthy went after the Army, that was too dear to Eisenhower’s heart. And he realized that was McCarthy’s Achilles heel. And behind the scenes, he orchestrated a campaign that did him in.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: The hearings were the first to be televised since 1948’s proceedings against Alger Hiss, the government official who stood accused of spying for the Soviet Union.

Larry Tye: So, the decision to publicize the hearings through television cameras, through having more reporters than had probably ever covered a congressional proceeding, was made, I think, in a number of ways. One is McCarthy’s committee. When he was relieved temporarily of his chairmanship in terms of overseeing these hearings on him as well as the Army, I think that the committee wanted to show the public that it was open, and that even though they were investigating one of their own, they were willing to let in TV cameras. But I’m sure they were under tremendous pressure. The TV networks—and back then, there were three TV networks that mattered—the TV networks understood that this was going to be great drama. It was America’s most famous red-baiter against America’s most sacred institution, the US Army. And that made for great television.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: Boston attorney Joseph Welch was brought in to serve as chief counsel to the Army. Born in Iowa, he was the youngest of seven children, and after graduating from Grinnell College, he left his small town life for Harvard Law School. With World War I raging, he enlisted in the Army shortly after. While he was in officer training school in Kentucky, the armistice was called, and he was discharged in November 1918.

He returned to Boston, and became a partner at the law firm Hale and Dorr in 1923. In 1954, he and two associates at the firm agreed to represent the Army pro bono.

Larry Tye: And he was a short, wiry Irish guy with an extraordinary sense of humor and an extraordinary sense of how to come in and look like he was an affable character, but he knew when to go for the jugular. And he was the perfect guy to be representing the Army.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: The televised proceedings turned contentious almost immediately, and the Army accused McCarthy of using his position in the Senate to get preferential treatment to close friend of Cohn, aide G. David Schine.

Larry Tye: So, after they got done looking at what was going on at the Army, the committee zeroed in on Joe McCarthy. And it showed behind the scenes he was using his power to get special treatment for himself everywhere, from going to fancy restaurants to generally being able to intimidate everybody all the way up to the secretary of the Army—who was not an especially strong character, a guy named Stevens, and McCarthy bullied him. And it also showed that he let his aide, Roy Cohn, go wild; but even more, this junior staffer named David Schine, who was out there supposedly doing his military service and was given special treatment so that he could get off for weekends, so that he had to do none of the grunt work that everybody else who was a low-level private in the US Army had to do. And that was using McCarthy’s privileges as a senator in an abusive way that suggested that even as he was bullying the Army for bad behavior, he was being a bully in enabling his staff to do things they shouldn’t have been able to do.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: McCarthy contended that the Army’s accusations were made in bad faith, and merely retaliation for his exposing alleged communists in the Army.

To his supporters, and behind the scenes, McCarthy mocked the proceedings, and downplayed the charges against him.

Archival Audio – Joseph McCarthy Mocks the Army Proceedings: Well, first, let me say, and I think the American people are beginning to realize this more and more, this is no contest as some of the left wing papers have tried to lead you to believe. Between McCarthy and the Army, I think that I have more support, and all of my mail’s contacts to those in uniform indicate that I have more support in this attempt to expose the few rotten apples in the barrel in the Pentagon, much more support for men in uniform than uh, those out of uniform.

I’d like to make it very clear if I could, and I’m sure there will be more and more clear as we go along. This is merely a contest. We’ll have to decide whether or not a few civilians in the Pentagon can hold up the work of a congressional committee that tries to dig out the few rotten apples in the barrel.

Now, as I said originally, I thought this was a complete waste of time. I was afraid nothing would be gained by it. Uh, in the end, if we decide who shined, shines the shoes, I don’t think that’s a great national issue.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: McCarthy believed he was untouchable. Each day, in front of the network cameras, his attacks became more brazen. Millions of Americans watched as he railed against the Army, his five o’clock shadow and beads of sweat on his forehead all the more prominent under the hot television lights. To many viewers, he came across as a madman.

Larry Tye: This is a moment in the hearings where Joe McCarthy, after promising not to go after Welch’s young associate named Fisher, McCarthy had agreed that the Army wouldn’t go after things that he didn’t want revealed, and he wouldn’t say anything about this young lawyer, Fisher. And McCarthy broke his vow. Roy Cohn, even the outrageous Roy Cohn, was shocked that McCarthy was attacking Fisher. And I’m convinced that Joe Welch had had in his pocket a rehearsed line, that he knew, at some point, McCarthy would overstep in the hearings. And so, with TV cameras looking on, tens of millions of Americans watching the drama here, Joe Welch says to McCarthy what may have been the most famous words ever uttered in a congressional hearing or in any legal proceeding.

Archival Audio – Joseph Welch Shames Joseph McCarthy: Welch: At this moment, Senator, I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness. Have you no sense of decency, sir? At long last, have you left no sense of decency?

McCarthy: I know this hurts you, Mr. Welch…

Welch: I’ll say it hurts!

McCarthy: But may I say, Mr. Chairman, as a point of personal privilege, I’d like to finish this.

Welch: Senator, I think it hurts you too, sir!

Larry Tye: And I think what happened was that at that moment, you watched in the hearing room, there was a hush, and everybody in that room understood McCarthy’s overstepping and Welch’s brilliance, with one exception. The one guy who didn’t get it was Joe McCarthy himself. And during the recess, he was essentially shaking his head, saying, what just happened?

Rebecca Naomi Jones: McCarthy’s downfall had begun, and footage of the confrontation dominated the front pages and the hearing’s recaps on the evening news broadcasts. The hearings came to an end in the summer of 1954, and in the aftermath, Republican Senator Ralph Flanders introduced a resolution calling for McCarthy’s censure.

Larry Tye: They voted substantially to censure him, to essentially cast him as an outsider. And for the rest of his time in the Senate, while he served out the remainder of his term—the rest of his time in the Senate, he was an outcast, and nobody wanted to have much of anything to do with him, even his biggest backers during his rise to power.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: On May 2, 1957, at the age of 48, Senator Joseph McCarthy died. The official cause of death was listed as quote “hepatitis – acute, cause unknown.”

Larry Tye: We didn’t know exactly what had happened to him in terms of his health, until one day I was up for an early morning walk with my wife and my dog on Cape Cod, and I saw at the foot of my driveway a large brown box. And I had been trying for more than a year to get the US Marine Corps to release Joe McCarthy’s medical records. After fifty years, the government has the right to say these are public record if somebody is enough of a public figure and if they decide to say yes. And the government generally says no. And somebody in the military decided that it was worth the public seeing Joe McCarthy’s medical records, especially the records from Bethesda Naval Hospital. And what those records showed was from the time of his censure by the Senate until his death, McCarthy was drinking the equivalent of a quart of whiskey every day, and that, while there was lots of debate, after he died, what he died of, and the official story was that he died of hepatitis, essentially, we now know that Joe McCarthy drank himself to death.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: As for Roy Cohn, he resigned from McCarthy’s staff in the wake of the Army hearings. He moved back to New York and entered private practice, where he found a niche representing mafia dons, nightclub and gentlemen’s club owners, and real estate tycoons.

Larry Tye: He became the ultimate fixer in New York. Whether you were Donald Trump or whether you were a politician of any stripe, Roy Cohn was the guy you brought in and paid a fortune to develop your media strategy, to develop your legal strategy, and to make you into a prominent public figure. And Roy Cohn also took on his nemesis, Bobby Kennedy, who wanted to go after Roy Cohn and did when he was attorney general but never successfully convicted him.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: Cohn was charged three separate times for allegations including perjury and witness tampering, and though he was acquitted each time, he was ultimately disbarred in 1986 by a panel of five New York State Supreme Court judges, who cited a host of examples of unethical conduct that included lying on his bar application, falsifying at least one client’s will, and misappropriation of multiple clients’ funds.

On August 2, 1986, Cohn died at the age of 58 from complications related to the AIDS virus; a diagnosis he denied until the very end. A patch dedicated to him on the AIDS Memorial Quilt, embroidered in stitched black, red, and yellow letters, reads:

“Roy Cohn. Bully. Coward. Victim”

Larry Tye: He was part of what became known as the Lavender Scare, which went along with the Red Scare. And the idea that this guy was enough of a hypocrite to help McCarthy go after gays when he was gay, to help McCarthy go after Jews when he was Jewish, and to generally deny his sexuality even after he developed AIDS, and it was Roy Cohn going out the way he had come into the public scene, which was with hypocrisy.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: McCarthy also left behind a complicated and controversial legacy – one that continued to resonate for decades after his death.

Larry Tye: The only thing more tumultuous than his rise to power was the idea that his career ended that quickly. And while Joe McCarthy was a name that was repudiated and became part of the notion of evil in America, McCarthyism persisted, I think, long after; that McCarthyism didn’t die with McCarthy. We had demagogues who modeled themselves precisely on McCarthy’s playbook, not only with people like David Duke and George Wallace, but with more modern demagogues who borrowed every trick in McCarthy’s book.

Archival Audio – Edward R. Murrow’s No Fear Editorial: There is no way for a citizen of a republic to abdicate his responsibilities. As a nation, we have come into our full inheritance at a tender age. We proclaim ourselves as indeed we are, the defenders of freedom wherever it continues to exist in the world. But we cannot defend freedom abroad by deserting it at home.

The actions of the junior senator from Wisconsin have caused alarm and dismay amongst our allies abroad, and given considerable comfort to our enemies. And whose fault is that? Not really his. He didn’t create this situation of fear, he merely exploited it. And rather successfully. Cassius was right. The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.

Good night, and good luck.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: From the American Jewish Historical Society, I’m Rebecca Naomi Jones. This episode was written by executive director Gemma R. Birnbaum. Recording, sound design, and mixing were done at Sound Lounge. Transcription is provided by Adept Word Management. Archival material is courtesy of the collections of the American Jewish Historical Society, the US National Archives, the CBS News Archives, Critical Past, the Library of Congress, the Department of Special Collections and University Libraries – Marquette University Libraries, and Periscope Films.

For episode transcripts, additional resources, and links to the collections featured in this episode, visit ajhs.org/podcasts. If you enjoyed this episode, please rate and review us on your preferred podcast platform which helps others discover our series.