In 1940, a very politically charged year for America, debates were held on the benefits of adding questions to the census that some thought could unfairly target and endanger segments of the population.

As the United States prepares for the 2020 census, the Supreme Court recently passed a ruling on the issue of whether questions regarding citizenship belong on the census. As with many current events, this litigation provides AJHS with an opportunity to look to our collections to determine how these materials can be used to provide historical insight into issues such as these.

In this case, we can look at the papers of Dr. Harry Linfield to shed light on historical debates with regard to census questions, and how American Jews have responded to these issues in the not-so-distant past.

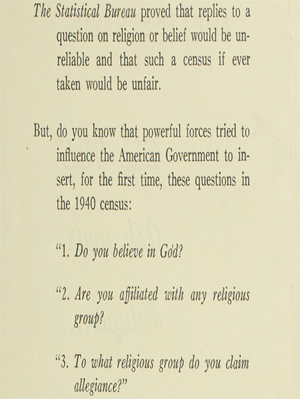

For the 1940 census, it was proposed that three additional questions be added, all three of which concerned religious affiliation and observance. The suggested questions were:

- Do you believe in God?

- Are you affiliated with any religious group?

- To what religious group do you claim allegiance?

These potential additions caught Dr. Harry S. Linfield’s–a rabbi and statistician who had published extensively on Jewish demographics and statistics–attention. Over the course of his distinguished career, Linfield worked for the Statistics Bureau at the Synagogue Council of America, and as the Director of Information and Statistics of the Bureau of Jewish Social Research (a division of the American Jewish Committee). Linfield had spent a great deal of his professional life devoted to collecting accurate statistics about the Jewish community at large, but had grave concerns about adding religious questions to the census.

His daughter, Hadassah Linfield, wrote in her introduction to his papers: “My father worked tirelessly to forge agreement with the Census Bureau to guarantee that neither Jews–nor members of any other religious group–be asked their religion on the population census–because doing so could provide a means for ill-intentioned individuals or groups to use the information to target or otherwise ostracize people based on their religious beliefs.” Dr. Linfield himself had emigrated from Lithuania to the United States in the early 20th century to escape the anti-Jewish pogroms, and after the Holocaust he was even more resolute in his belief that religion should not be documented on the individual level.

It was one thing to document religious bodies as a whole (size of congregations, communities, geographical distributions, etc), but collecting individual records of religious affiliation was, to Linfield, a bridge too far. We at AJHS are fortunate to be the repository of Dr. Linfield’s personal and professional work, and thanks to a generous gift from his family, we are able to offer digital access to hundreds of pages of materials in the collection. This enables scholars from all over the world to read his work, and be aware of the history behind the questions that make their way onto your census form.

More on Dr. Linfield’s work can be found in the collections of the American Jewish Historical Society.