As we relax into high summer, the staff at AJHS reminisce about years past, especially those long, sunny days spent, not confined to the air-conditioned environment of the archives, but outside at summer camp: most probably sneaker-footed, and definitely not air-conditioned. In 2024 alone, 189,000 youths attended Jewish camps across the country, an increase of 5% from the prior year.1 Over the decades, we’ve seen cultural shifts in almost every imaginable facet of American life, but one thing remains largely the same: after the last school bell rings and just before summer boredom sets in, thousands of children head en masse to camp, as they’ve since the late 19th century.

Recreational camping as we know it today was largely a response to the increasing urban population in the United States at the end of the 19th century; by 1890, 29% of Americans were living in cities.2 This statistic can likely be attributed to the surge of immigration at the turn of the century. Between 1880 and 1924, for example, as many as 3 million Eastern European Jews immigrated to the U.S., most settling permanently in New York City.3 With such a tremendous influx of residents in so short a time, city dwellers suffered unimaginably cramped quarters, poor hygiene & rampant disease, with limited resources to improve their situation.4

Sleepaway camp was born from a philanthropic endeavor to provide children predominantly from working-class and immigrant families with a respite from an often dangerous, dirty, and hot summer in the city.5 As fresh-air programs grew, some summer camps were intentionally established to cater to Jewish youth, with the additional objective of cultivating a strong American Jewish community outside of an American culture that was predominantly Christian.6 Boys and girls would make new friends surrounded by nature, learn about personal responsibility and hygiene, have seemingly endless opportunities to explore new sports and hobbies, and in many circumstances, cultivate pride in their Jewish heritage in a country where antisemitism was on the rise.7 For some, the celebration of religious rituals, songs, and traditions was life-affirming and life-changing.

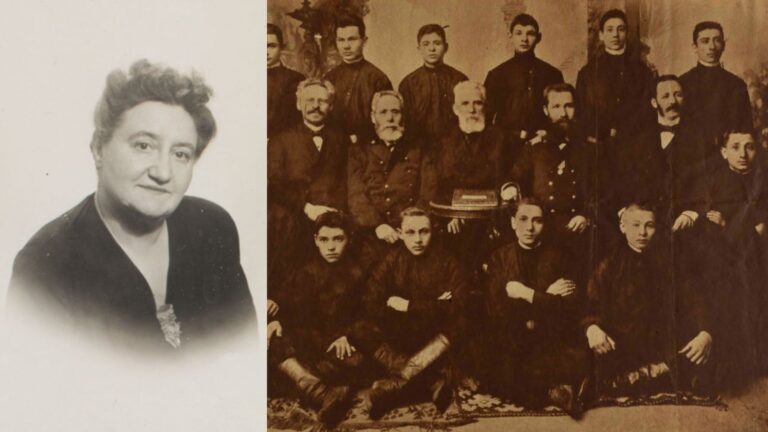

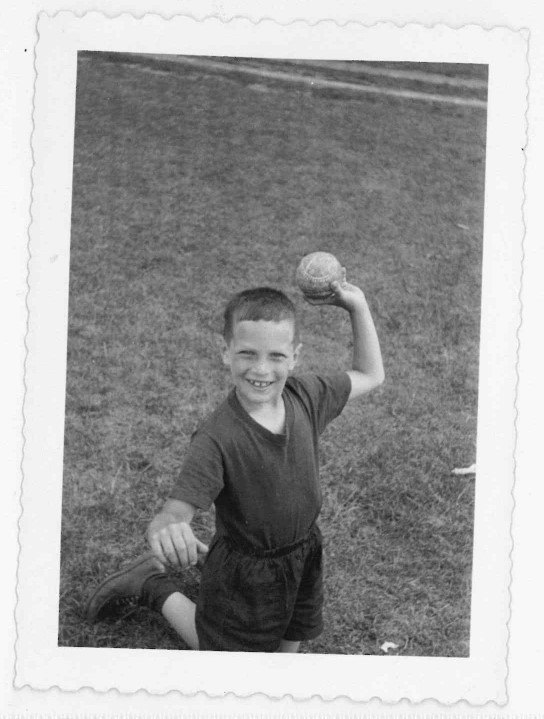

By the end of World War II, sleepaway camps in the U.S. served an important role in keeping Jewish culture alive in the wake of the Holocaust.8 Post-war America saw a significant increase in participation, and Jewish Summer Camps grew to become a prominent coming-of-age experience for many American Jews that is still common to this day.9 In the AJHS archives, we house a rich collection of material from former staff, campers and counselors of Camp Massad, the pre-eminent Hebrew summer camp in the United States during its time. Ranging in date from the 1940s to the early 2000s, this collection is invaluable and treasured for its preservation of the daily life and activities of those attending Camp Massad, such as baseball, volleyball, and gardening, to name a few!

Boy with baseball, Camp Massad Aleph, 1953. I-550, Box 7, Folder 5.

Boys playing volleyball, Camp Massad Aleph, 1953. I-550, Box 7, Folder 5.

“The girl’s garden group” Camp Massad Aleph, 1949. I-550, Box 7, Folder 5.

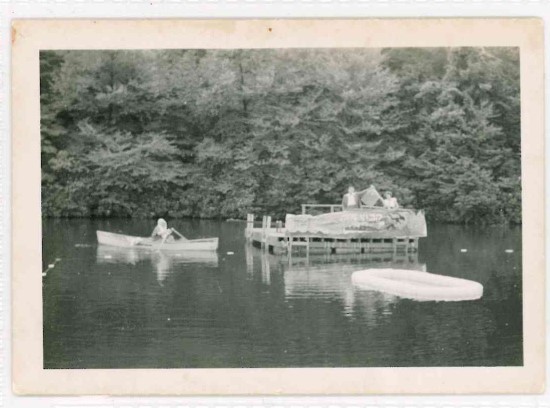

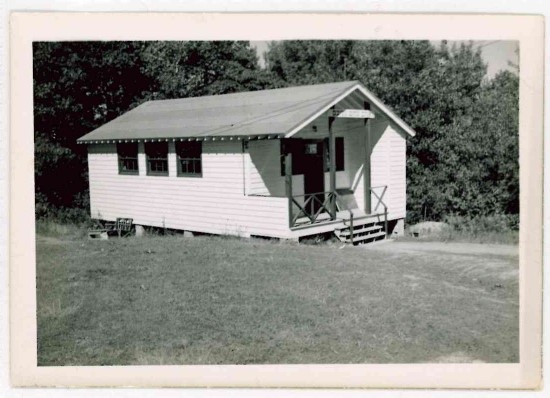

The Camp Massad collection also contains photographs of the camp grounds. In 2025, in summer camps throughout the country, you will still find laundry drying on outdoor lines, canoes lying sleepily on the water waiting to be rowed out to the deep, and simple one-room cabins where youth sleep without the modern conveniences we’ve all come to know so well – just as is demonstrated in the below photographs from 1949.

Dock, swimming gear, and a canoe on the lake, Camp Massad Aleph, 1949. I-550, Box 7, Folder 5

“My clothes hanging out to dry”, Camp Massad Aleph, 1949. I-550, Box 7, Folder 5.

Cabin at Camp Massad Aleph, 1949. I-550, Box 7, Folder 5.

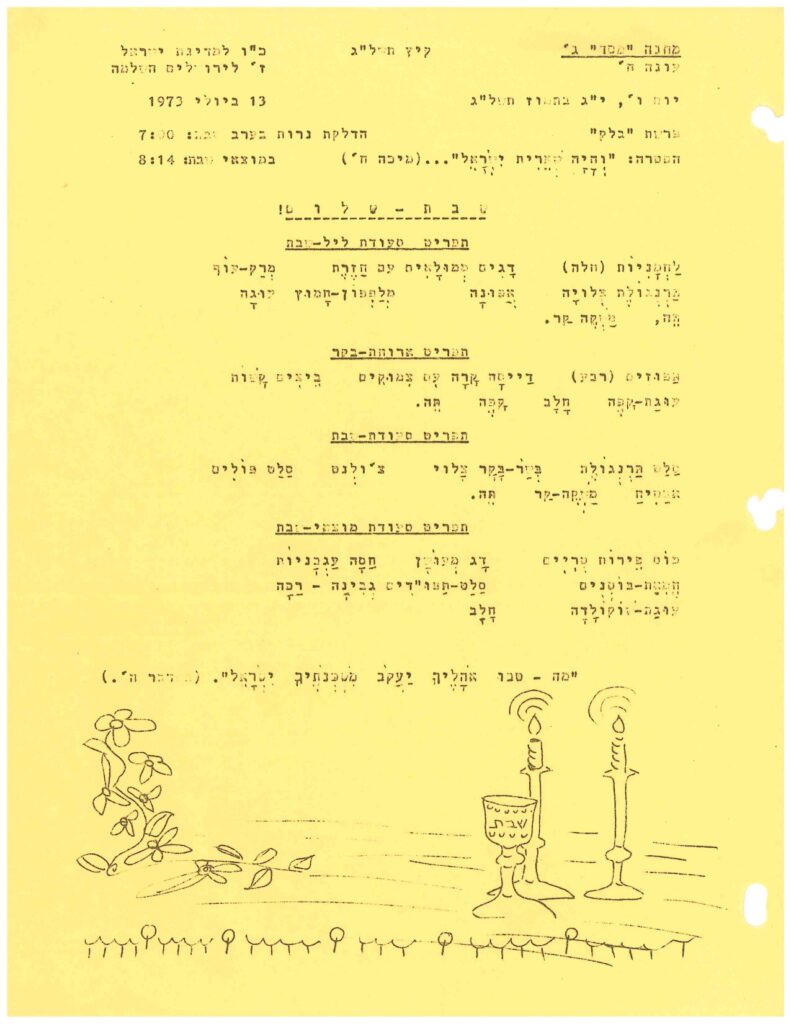

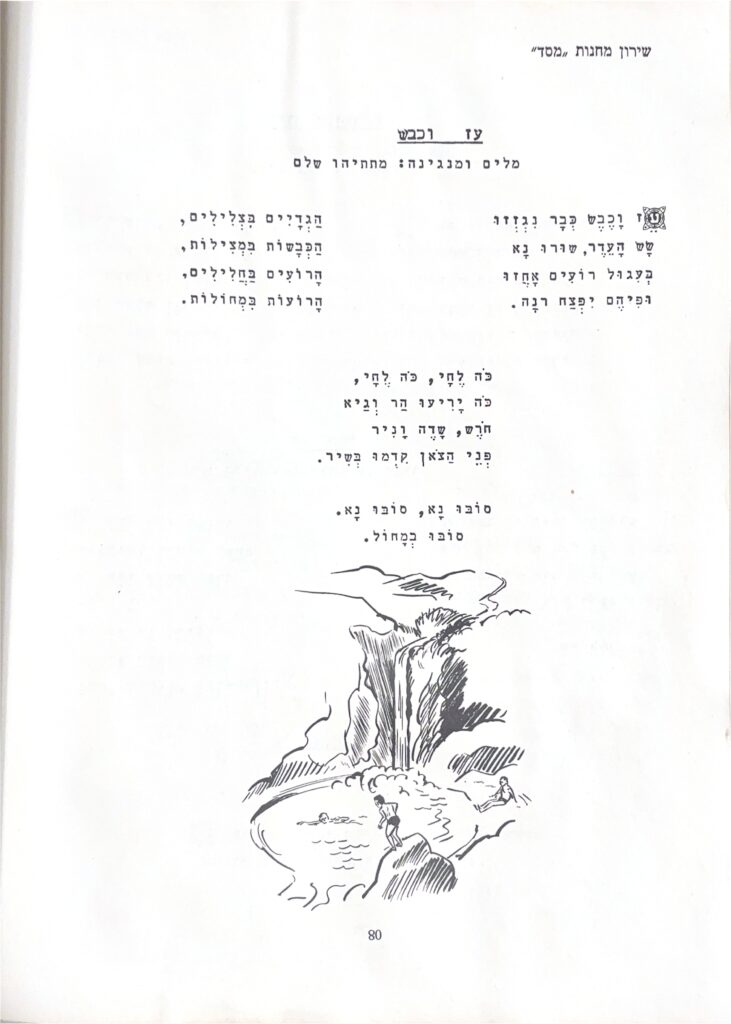

Camp Massad was founded in 1941 and experienced significant growth by the time of its peak in the 1960s. The camp boasted three separate sites, Massad Aleph (featured in the above photographs), Massad Bet and Massad Gimel. Evidenced by the photographs within the collection, campers were exposed to even more opportunities to learn and grow than perhaps originally intended by the organizers of the fresh-air movement. Urban youth traveling to Pennsylvania for the summer at Camp Massad would spend their days swimming in natural waters, playing ball games in large, grassy fields, and cultivating lifelong friendships. However, what made this experience special as a Jewish summer camp was the cultural immersion. The use of Hebrew was prolific, and eventually, the summer camp published its own Hebrew-English dictionary, which included new vocabulary to describe American sports. Campers sang songs around the campfire in Hebrew, celebrated Shabbat as a community, and participated in Maccabia, or Color War. Jewish culture was the cornerstone of the Camp Massad experience, along with a robust songbook.

Sabbath Menu, Camp Massad, 1973. I-550, Box 5, Folder 4.

Song Sheet, Camp Massad, undated. I-550, Box 5, Folder 5.

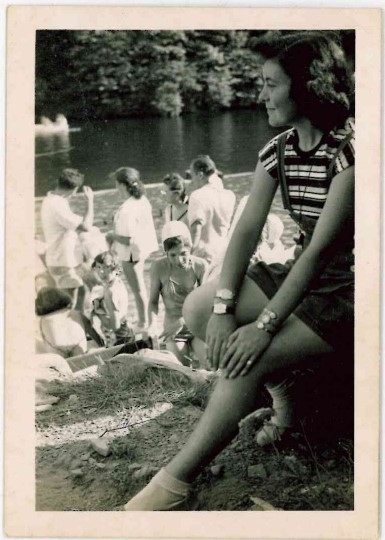

Girl wears multiple wristwatches as youth swim in lake below, Camp Massad, undated. I-550, Box 7, Folder 3.

You can view these photographs and hundreds more, in addition to yearbooks, counselor manuals, play scripts, etc., via the Camp Massad Records I-550.

To learn more about the Jewish summer camp experience post WWII, listen to AJHS’ podcast The Wreckage: Episode 106 – The Advocates.

______________________

Foundation for Jewish Camps, CENSUS REPORT: STATE OF JEWISH CAMP 2024, 2, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://jewishcamp.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/FJC-Census-Report-2024.pdf. ↩︎

Robert P. Porter, “Urban Population in 1890,” U.S. Census Bureau, April 17, 1891, No.52, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1890/bulletins/demographics/52-urban-population-in-1890-cities-8000-inhabitants.pdf. ↩︎

Library of Congress. n.d. “Polish/Russian | Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History | Classroom Materials at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress.” Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/polish-russian/a-people-at-risk/. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Museum of Jewish Heritage, “An American Jewish Tradition: Sleepaway Camp,” July 1, 2021. ↩︎

Gary P. Zola, “The History of American Jewish Summer Camps,” Museum of Jewish Heritage, July 9, 2021. ↩︎

Museum of Jewish Heritage, “An American Jewish Tradition: Sleepaway Camp,” July 1, 2021. ↩︎

Deena Prichep, “Jewish summer camps are an American tradition rooted in World War II,” June 11, 2023, National Public Radio, radio broadcast, https://www.npr.org/2023/06/11/1181547724/jewish-summer-camps-are-an-american-tradition-rooted-in-world-war-ii. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎