The word ‘pirate’ conjures a very specific image for most: men hardened by wind, sun, salt, disease and poor nutrition sailing to far flung coasts for treasure lying at the bottom of the sea or trapped in the hands of a powerful monarch. However, what we know of pirates or rather, privateers, from our own collection, is something much different.

At the time of the American Revolutionary War, the British Royal Navy was the most sophisticated and powerful naval force in the world.1 It was out of pure necessity that the Continental Congress in 1776, facing a mighty enemy of the seas, formalized the commissioning process of privateers to disrupt British commercial shipping and secure the safety of American shores. Acting under the auspices of the Continental Congress, privateers were civilians, who harassed—with the goal of capturing—British ships and their cargo. The successful privateering patriot would then be rewarded with the profit of the sale of the ‘prize’.2 In defending their burgeoning country, privateers were also amassing personal gain in the process.

Mordecai Sheftall, of Savannah, Georgia, is one such privateer and we at the American Jewish Historical Society steward his war records, among other papers. A guide to his collection was originally processed by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1941.

A successful merchant, landowner and distinguished religious leader in his hometown of Savannah, Mordecai had made a name for himself before hostilities with Britain took hold in the young colony. His father, Benjamin, and mother Perla were among the first 43 Jews to immigrate to Savannah shortly after its initial founding, in 1733.3 Benjamin was a well-respected businessman, a trait that he passed down to Mordecai, who by the time he was seventeen, had created a modest business buying and tanning deer hides4 It wasn’t until 1756, at the age of twenty one, that Mordecai was granted his first plot of land, and fifty acres at that, with the stipulation that it would be properly cultivated.5 After years of accumulating real estate in Georgia, Mordecai Sheftall, joined by his wife Frances whom he married in 1761, owned 650 acres later used for cattle ranching and timber harvesting.6

When rumors of revolution began circulating throughout the colonies, the Sheftalls staunchly sided with the patriots; Mordecai proudly acted as founding Chairman to the Parochial Committee of Savannah, a group of men committed to the patriot cause and spurred by the blockade of Boston Harbor in 1774.7 In short, Mordecai was a devoted revolutionary from the outset.

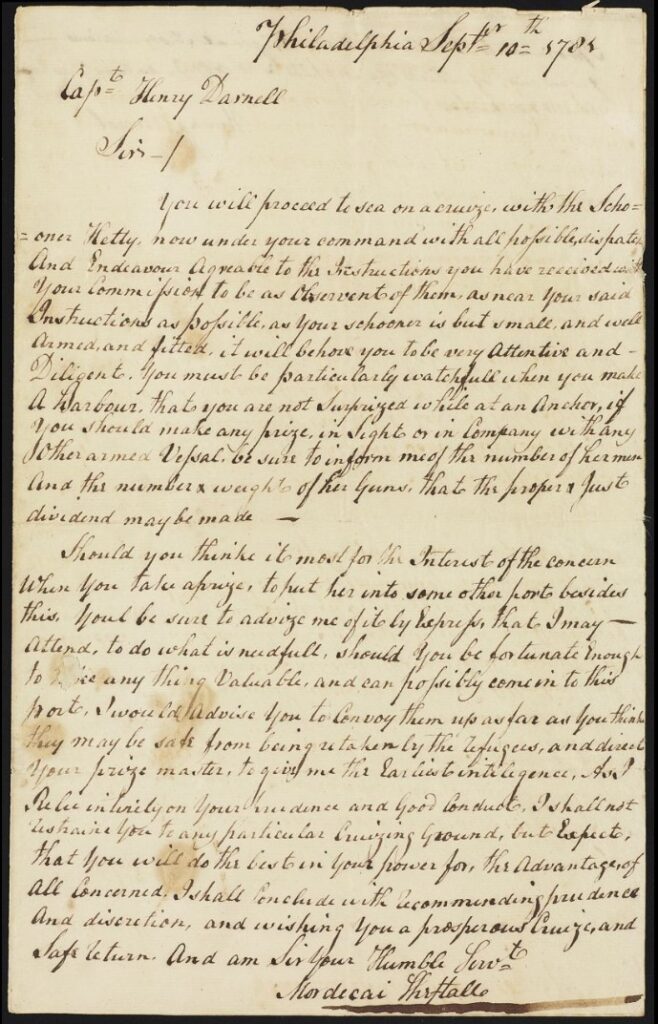

His first official role in the war of 1776 was Assistant Deputy Commissary of Issues for Georgia, responsible for purchasing and distributing food to Continental soldiers. It was commonplace at the time for commissioners to purchase supplies using their own money, as the nascent government did not have the funds necessary to support the maintenance of the army on its own. Mere months after a promotion in 1778, however, Sheftall was taken prisoner by the British during Savannah’s occupation in December and spent the next two years or so in British custody. Upon being released as a result of a prisoner exchange, Mordecai purchased the two-masted Schooner Hetty, first captained by Henry Darnal, and began his short but well-documented privateering career.

In the above letter, Mordecai, now-owner of the Hetty, gives instructions on the upcoming ‘cruize’ on which captain Darnal will soon embark in September 1781. Mordecai warns his captain, writing “as your schooner is but small, and well armed, and fitted, it will behoove you to be very attentive when you make a harbour. That you are not surprised while at anchor, if you should make any prize, in sights or in company with any other armed vessel, be sure to inform me of the number of her men and the number & weight of her guns, that the proper & just dividend be made.”

Mordecai signs off with well wishes, writing “I shall conclude with recommending prudence and discretion, and wishing you a prosperous cruize, and safe return, and am sir your humble servant.”

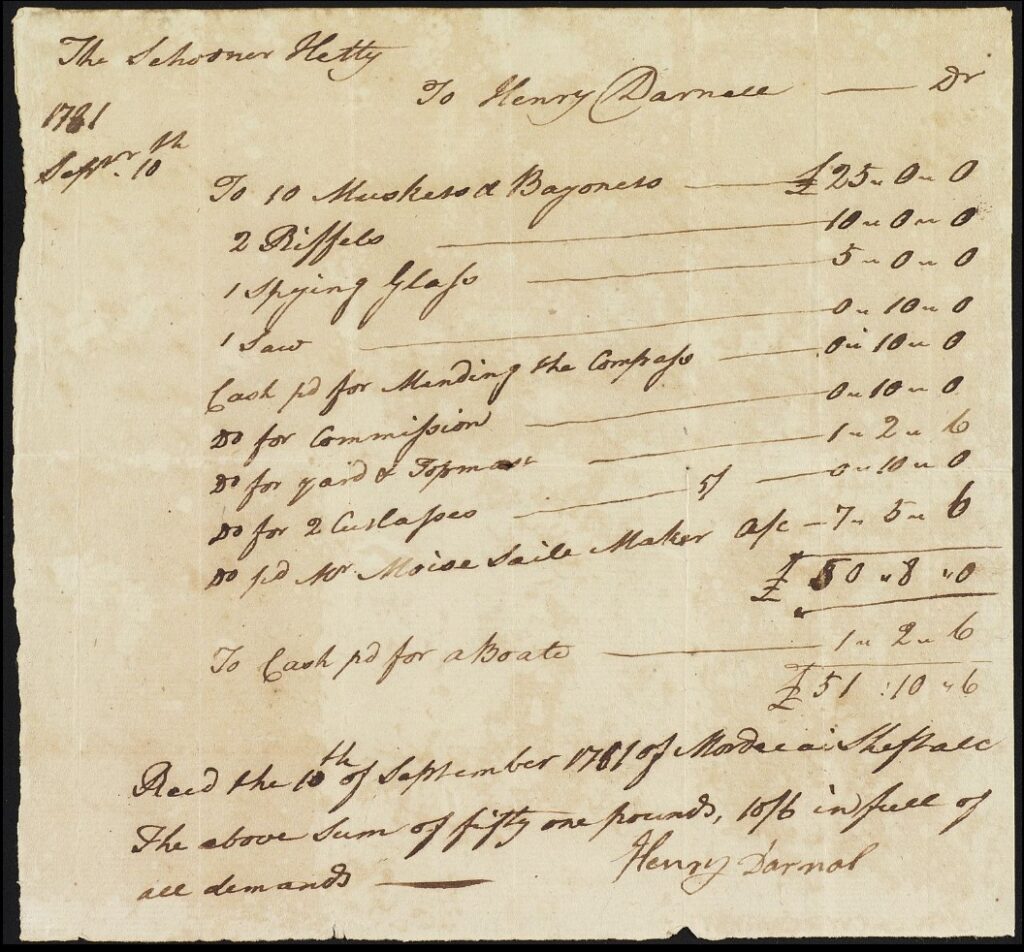

A receipt written on the same day as the above, September, 10th 1781, lists the goods that Sheftall received from Captain Darnal and later exchanged for a total of 51 pounds, 10 shillings and six pence:

- 10 Muskets & Bayonets – 25 pounds

- 2 Riffels – 10 pounds

- 1 Spying Glass – 5 pounds

- 1 Saw – 10 shillings

- Cash paid for mending the compass – 10 shillings… etc.

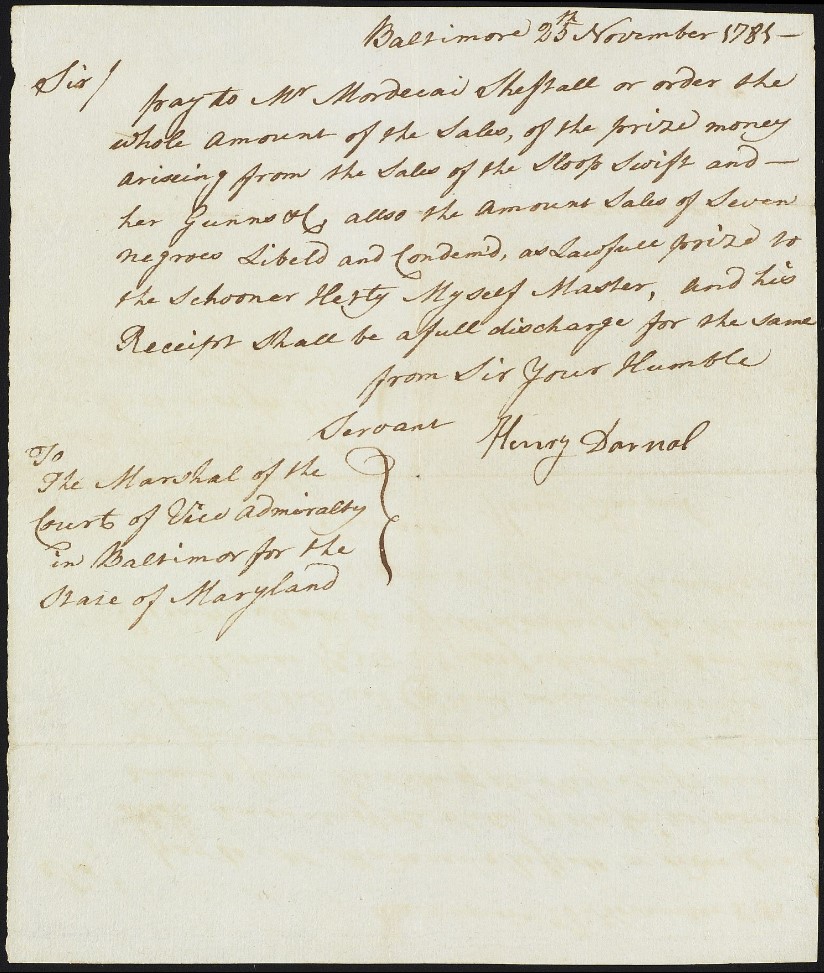

As we well know, the beginning of the American Revolution did not mean an end to the transatlantic slave trade, and thus human beings were also contained in The Ledgers containing correspondence between privateers and their ship captains also list enslaved persons. Mordecai Sheftall was no exception. In a letter from Henry Darnal on November 25, 1781, he writes ‘Sir I pay to Mr. Mordecai Sheftall…the prize money arriving from the sale of the sloop Swift and her gains of also the amount sales of seven negroes’.

Mordecai Sheftall’s privateering activities spanned the length of the war and his renown as a committed patriot reverberated through to his family and their lasting prosperity. The Sheftalls of Georgia were founders of Congregation Mikve Israel, and Mordecai played a significant role in its re-establishment in peacetime.8

Sheftall’s papers shed tremendous light on what it meant to be a revolutionary privateer, as well as preserving the broader social, political, and economic context of his career. As an historical society, we know it is of the utmost importance to acknowledge that Sheftall’s prosperity could not have been possible without the trafficking of enslaved people, as is true of the success of the Revolution and the founding of the United States as a result. While narratives of pirates and privateers are often romanticized in popular culture, we know from primary sources such as these that the story is far more complex and asks for further reflection. We invite you to engage with these and other collections online and in person at AJHS.

___________________________________________________

- “The Royal Navy during the American Revolution.” 2020. American Battlefield Trust. December 10, 2020. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/royal-navy-during-american-revolution. ↩︎

- Frayler, John. n.d. “Privateers in the American Revolution (U.S. National Park Service).” Www.nps.gov. https://www.nps.gov/articles/privateers-in-the-american-revolution.htm. ↩︎

- Morgan, David T. 1973. “The Sheftalls of Savannah.” American Jewish Historical Quarterly 62 (4): 348–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/23878075. ↩︎

- Cooksey, Elizabeth. “Mordecai Sheftall.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. Accessed January 2, 2025. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/mordecai-sheftall-1735-1797. ↩︎

- “The Sheftalls of Savannah.” 350. ↩︎

- Morgan. “The Sheftalls of Savannah.” 351.; Cooksey. “Mordecai Sheftall”. ↩︎

- Hühner, Leon. 1909. “THE JEWS of GEORGIA from the OUTBREAK of the AMERICAN REVOLUTION to the CLOSE of the 18TH CENTURY.” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society, no. 17: 89–108. https://doi.org/10.2307/43057796. ↩︎

- Morgan, David T. 1973. “The Sheftalls of Savannah.” American Jewish Historical Quarterly 62 (4): 348–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/23878075. ↩︎