Every Passover, Jewish families around the world do their best to stay creative with matzo. Yet, by the end of the week, it’s a struggle. In 1871, Esther Levy dedicated a small section of her Jewish Cookery to this matzo fatigue, and offered her readers a solution in the shape of Matzas Charlotte: a dessert comprised of softened matzo layered with fruit and custard.

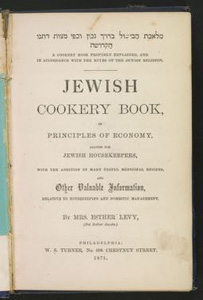

A Cookery Book Properly Explained, and in Accordance with the Rules of the Jewish Religion, Jewish Cookery Book, or Principle of Economy, Adapted for Jewish Housekeepers, with the Addition of Many Useful Medicinal Recipes, and Other Valuable Information, Relative to Housekeeping and Domestic Management is notable as the first Jewish cookbook published in the United States. While little is known about its author, Mrs. Esther Levy (neé Jacobs), she writes in a strong encouraging voice.

Many of Levy’s recipes are about aspirational cooking–ensuring her readers know that they can eat like an American middle-class family while maintaining an adherence to kosher law. Her recipes include gumbo made with okra, Philadelphia Pepper Pot soup cooked without the traditional tripe, and instructions for cooking kale.

When it comes to Passover advice, in her chapter on puddings she calls one recipe “Matzas Charlotte (unleavened bread for supper),” a Passover version of a popular dessert. “Charlottes” were invented in England in the late 18th century, named for Queen Charlotte, wife of George III. The dish became “Charlotte Russe” – or Russian Charlotte – in early 19th-century Europe, when Russian food and dining habits were en vogue.

The dessert could be composed of many layers of custard flavored with mace (a part of the nutmeg fruit), vanilla beans, almonds, peach leaves or cinnamon, all mixed with lemon and brandy whipped cream. It was then layered with almond cake, frosted with rose or lemon-flavored royal icing, and decorated with strawberry slices or white grapes.

By the end of the century, Charlotte Russe recipes had become simpler and standardized. For example, one recipe called for ladyfingers or sponge cake pressed into a round mold, the center filled with whipped cream, custard, or blancmange stabilized with gelatin. By the early 20th century, pre-packaged, commercial ladyfingers were available to consumers. This simpler, not to mention cheaper, version of Charlotte Russe became available in New York City in the early 1900s.

Sometimes called “Charley Roose,” for 3-5 cents a kid in Brooklyn could head to a local bakery, and purchase a confection made from cake scraps topped with whipped cream, chocolate sprinkles, and a maraschino cherry. Lyn Stallworth and Rod Kennedy, authors of The Brooklyn Cookbook, recounted that the dessert was “surrounded by a frilled cardboard holder with a round of cardboard on the bottom. As the cream went down, you pushed the cardboard up from the bottom, so you could eat the cake … these were Brooklyn ambrosia.” According to a Politico article by Leah Konig, Holtermann’s Bakery in Staten Island is perhaps the only New York City bakery that still makes these treats. And yes, Levy’s cookbook has a Kosher for Passover version.

Matzo Charlotte (Modernized)

Soak about three matzas (cakes) in cold water. When tender, strain them dry on a sieve by layering each piece separately. Have ready some butter and raisins, grated peel, nutmeg, cinnamon, and sugar. Lay the matzos on a dish in layers, and put the fruit on with a good custard prepared with one quart of milk and seven eggs, well beaten, with four ounces of white sugar and a stick of cinnamon.

Ingredients:

(for the custard)

- 4 cups whole milk

- 1 stick cinnamon

- 5 large eggs, divided

- 1 cup sugar

(for the cake)

- 1 cup dried fruit

- 2 tbsp butter

- Zest of half of a lemon

- ½ tsp cinnamon

- ½ tsp nutmeg

- 3 matzos

Instructions

- For the custard, add cinnamon stick and milk into a saucepan.

- Bring pan to a boil over medium heat.

- While the pan is heating up, whisk together the egg and the ½ cup sugar in a glass or rubber-bottomed bowl.

- When milk comes to a boil, pour slowly into the egg mixture, whisking constantly. Return to saucepan and cook over low heat, stirring constantly with a wooden spoon, until custard thickens slightly and evenly coats the back of the spoon (it should hold a line drawn by your finger)

- Chill custard for at least three hours.

- Prepare the fruit: in a small saucepan, add fruit, butter, lemon zest, spices, remaining sugar, and 1 cup boiling water.

- Bring saucepan to a boil over medium-high heat, then reduce heat to medium-low and simmer for ten minutes.

- Chill for at least three hours.

- Soak the matzos each matzo in a bowl of water for 30 seconds. Drain on a wire cooling rack.

- Assemble the Charlotte: Lay one matzo in the bottom of a pie plate or cake stand.

- Spread with ½ cup custard and then sprinkle with ⅓ of the fruit.

- Repeat with remaining matzo, and decorate top with a sprinkle of cinnamon.

The Results

As I sliced into the dripping mass of Matzas Charlotte and scraped a serving onto my plate, the saturated strips of matzo clung to the serving dish like tentacles. I stuffed a wad of dessert in my mouth. The sludgy custard gave way to stringy matzo, and the tart fruit bursting in my mouth had the texture of plump beetles. The dessert lacked any real flavor, beyond the sensations of slightly sweet and sour. If I were a child in the 1870s who only had sweets on Passover, I’d love it.

However, there may be hope yet for this historical desert. Charlotte Russe has a British cousin, the trifle: layered cake, custard, and fruit topped with whipped cream, often displayed in a clear trifle dish designed to show off the layers. Consider using Matzas Charlotte as inspiration for a Matzo Trifle: softened matzo, layered with this recipe for rich custard (just don’t freeze it) and fresh fruit compote, and top it with real whipped cream. Or perhaps just take your inspiration from Brooklyn: top your matzo with some Kosher-for-Passover whipped cream in a can, a maraschino cherry, a scatter of sprinkles–and call it a day.