“And I have learned one of the most important lessons a historian can learn: always take a second look, even when you’re sure you’ve seen everything there is to see.”

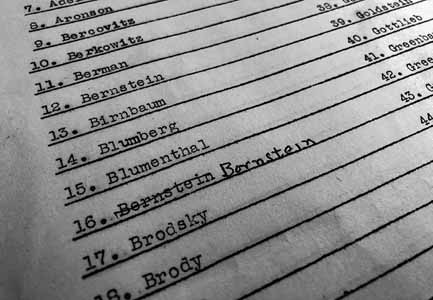

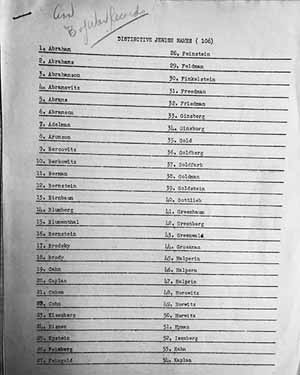

When I began my research on Jewish name changing 12 years ago, one of my first stops was the American Jewish Historical Society. I wanted to see if the society had any archival records of name changers, but they only had a few. I did find something else intriguing, however: the “distinctive Jewish name” (DJN) list (Box 82). It’s a list of 106 Jewish surnames (like Cohen and Goldberg) that the National Jewish Welfare Board developed during World War II to help count the Jewish community.

I didn’t know what to do with the list at first. I found it intriguing, but it wasn’t exactly what I was looking for. I was interested in the ways that ordinary Jews challenged and even rejected the boundaries of Jewish identity by eliminating their Jewish names. The DJN list reflected Jewish counting by communal leaders. How did they connect?

I spent the next several years at the New York City Civil Court, making photocopies of thousands of name change petitions submitted over the course of the 20th century, entering the information into databases, and trying to analyze the petitions. And as I considered and reconsidered my documents, I realized that the DJN list might mean more to me than I had originally realized. The petitions at Civil Court had fallen into a clear chronological pattern: they exploded exponentially during World War II, at the exact moment that the National Jewish Welfare Board was developing the DJN list. I went back to the AJHS to conduct research in the NJWB records.

And what I found was that there were important connections between the name change petitions and the DJN list. One crucial thing that linked them was their origins. Name change petitions exploded during World War II because of the rise of antisemitism—the same reason that the Jewish Welfare Board had developed the DJN list. While individual Jews changed their names because they were unable to find jobs or get into school, the Jewish Welfare Board developed a list of distinctive Jewish names to conduct a census of Jewish soldiers in the war, so that they could disprove rumors that Jews shirked war service.

The DJN and name change petitions were thus intertwined in their defensive stance against the bigotry and cruelty of the era. Perhaps the most important signal of this intertwining was the fact that roughly 30 percent of my name change petitions were submitted to erase one of these 106 distinctive Jewish names in 1942, names that reflected slightly less than 4 percent of the New York City population at the time. Jewish names were so stigmatized, so damaging to people’s chances of upward mobility in the 1940s, that they were erased at rates almost ten times their existence in the population.

As I looked more closely at the Jewish Welfare Board materials, I became more and more interested by the ways that these communal leaders talked about Jewish names and name changing. Members of the JWB continuously explained that they sought all Jews for their census, not just those with Jewish names. They went out of their way to note that census-takers should not listen to “the ‘sound’ of the name.” And they made clear that even if they disapproved of name changing (as indeed I found that some did), they included Jewish name changers as integral parts of the Jewish community.

It gradually became clear to me that my desire to study individual Jews challenging the boundaries of Jewish identity was inextricably linked with a need to look at Jewish communal leaders and their plans to identify, count, and measure the community. Jewish communal leaders wanted and needed to wrestle with Jews who challenged boundaries, just as Jews who challenged boundaries still found themselves tied to Jewish families, networks, and communities. Name changers did not abandon the Jewish community, and the Jewish community did not abandon name changers. They all engaged in the unhappy task of fighting hatred, just as they all worked to define the Jewish community together.

The DJN list is now hanging up in my office, one of the most prized documents from my research. And I have learned one of the most important lessons a historian (or anyone) can learn: always take a second look, even when you’re sure you’ve seen everything there is to see.