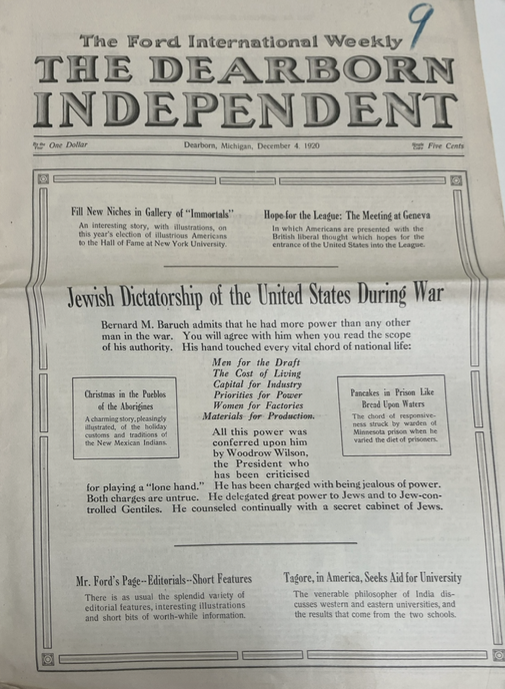

The headlines were bold and the stories were brutal: “JEWISH DICTATORSHIP OF THE UNITED STATES DURING WAR,” “JEWISH SUPREMACY IN THE MOTION PICTURE WORLD,” “ARE THE JEWS VICTIMS OR PERSECUTORS?” Throughout the 1920s, business magnate Henry Ford spread such vitriol through his newspaper, The Dearborn Independent, which reached a peak circulation of 900,000. Ford’s The International Jew—The World’s Foremost Problem, largely based on the fraudulent Protocols of the Elders of Zion that bespoke Jewish domination, first appeared in the paper and then as a series of booklets. Ford had founded the Ford Motor Company, which revolutionized American transportation with its production of the affordable Model T. The success had turned him into the world’s richest man. By nature of his wealth and celebrity, he wielded tremendous influence and used it to propagate antisemitic myths in an era of fear and uncertainty.

The precise origins of Ford’s “Jew mania” – as his critics described it – are unknown, but The International Jew ascribed every cultural and economic ailment to Jewish treachery. Ford acquired control of The Dearborn Independent in 1918 amidst a great deal of societal transformation. The Great War, the rise of Bolshevism, mass immigration to America, and changing sexual and gender norms had scandalized many. Each issue of The International Jew offered an explanation, blaming Jews for orchestrating the apparent downfall of Anglo-Saxon values. Editor William J. Cameron penned most articles, but the propaganda soared only with Ford’s stamp of approval. Ford even instructed his car dealers to distribute complementary copies of The International Jew to customers at a time when business was booming.[1]

The contents of The International Jew, which ran for ninety-one installments, depicted Jews as cunning criminals. According to its articles, the war had devastated millions but the Jews “found wealth in the debris of civilization.” Cameron observed “the Jew’s” tendency to overcome discrimination. “Forbid him in one direction, he will excel in another,” read one issue, and “when [the Jew] was forbidden to deal in new clothes, he sold old clothes.” But these were not the admirable characteristics of an industrious people. Instead, it represented an “unflagging ambition to get further up the ladder” at the expense of others. The International Jew also portrayed its targets as the agents of obscenity. The paper echoed the complaints of anti-vice activists who found that theatrical plays and movies were “reeking with filth” and “gravitate naturally to the flesh and its exposure.” Jews were held responsible for corrupting virtually every vessel of American economy: entertainment, sports, sugar, tobacco, grain, cotton, liquor, and more.

Against such attacks, Jewish civic leaders worked tirelessly to stop Ford’s publication. Louis Marshall, president of the American Jewish Committee, advised releasing statements to publicly refute Ford’s lies, “trusting in the good sense of the American people.” Several Jewish and non-Jewish writers dismantled the publication’s claims in secular papers. The Anti-Defamation League labelled Ford a “poison pen” – a person who spreads slander – while pointing out the many contradictions and fallacies of The International Jew. In 1927, Jewish attorney Aaron Sapiro went a step further and sued Ford for libel after the paper accused him of exploiting farmers. Facing mounting pressure and poor publicity, Ford agreed to end the lawsuit, close the paper, and issue a generalized apology to Jews. In a signed statement, Ford expressed his regret that Jews “regard me as their enemy” and denounced the paper’s “offensive charges.” In reality, Marshall drafted this repudiation himself at the behest of Ford’s legal team.

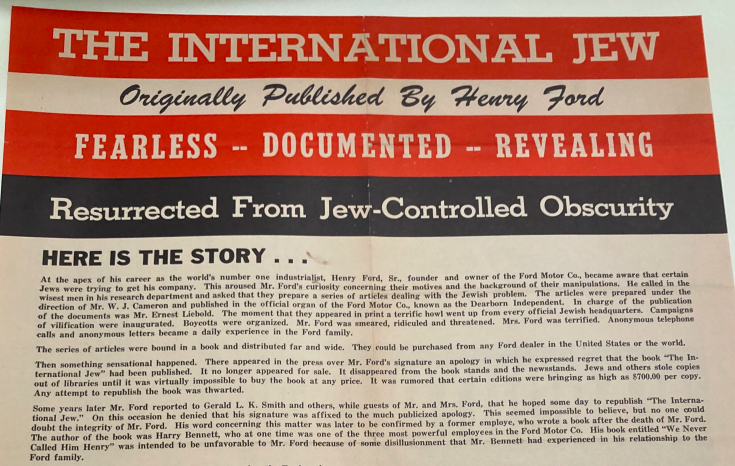

Regardless of Ford’s dubious retraction, his International Jew continued to shape antisemitic movements after the 1920s. During World War II, the Germans circulated a Spanish translation, “El Judio Internacional,” in Mexico City, hoping to cause discord in the Americas. The Christian Nationalist Crusade, a 1940s extremist group led by prominent rabble-rouser Gerald L.K. Smith, promised to “resurrect” the publication from “Jew-controlled obscurity.” They reprinted The International Jew and spun new narratives, lamenting that “Mr. Ford was smeared, ridiculed, and threatened” for sharing the truth. Ford had shown little remorse and accepted high honors from the Nazi regime in recognition of his antisemitic work. The International Jew’s vast reach and enduring legacy, which are documented in the AJHS archives, reveal how powerful individuals can weaponize media platforms to spread hate.

View the Admiral Lewis Lichtenstein Strauss Papers, P-632

View the Antisemitic Literature Collection, P-701

View the Louis Marshall Papers, P-24

[1] Pamela Nadell, Antisemitism, An American Tradition (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2025), 102.