Archival Audio, Truman Discusses Atomic Bomb:

Alright Mr. President, do you feel that it was right for Oppenheimer to have received a Fermi Award?

Truman: Yes. I think he earned it.

Was his work on the hydrogen bomb- that is, when he was offered the work on the hydrogen bomb he did not want to do it. Yet, you said to go ahead to work on the hydrogen bomb.

Truman: That’s correct. Well, he was like all the scientists are. They discover these things and find out how terrible they are and then they don’t want to take any blame for the consequences if there is blame. But that didn’t make any difference. He didn’t have to make the decision, I made it.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: On August 6, 1945, the United States became the first, and thus far only, nation to deploy the atomic bomb in a time of war. In two bombings days apart, the nuclear blasts devastated Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the surrounding areas. These weapons were the culmination of the years-long top-secret Manhattan Project, and as casualties in the Pacific continued to mount, President Truman deployed the most destructive and deadly weapon ever designed in an effort to force Japan into surrendering.

After the war, “father of the atomic bomb” J. Robert Oppenheimer, the Jewish American theoretical physicist and director of the Manhattan Project lab at Los Alamos, found himself at the center of anti-Communist panic, and at odds with his former professional ally, Lewis Strauss.

From the American Jewish Historical Society, this is The Wreckage: Year Zero. I’m your host, Rebecca Naomi Jones. This week’s episode, The Scientist, brings us into the Atomic Age.

Archival Audio, Atomic Test in Nevada:

The Nevada desert in America is the scene of the latest Atomic test. International observers come by invitation to join scientists, military and civil defense authorities making a study of the test. A whole town of specially chosen types of buildings with dummies inside them has been erected to study survival chances in an atomic explosion. Called Doomtown, the buildings and their contents will test the effect of the bomb at distances ranging from 1 to 2 miles. The extent to which food will be contaminated by radioactivity will also be studied, along with the effect of blast on communications. Fully protected cameras concealed inside and outside the buildings will take pictures of the blast.

[Music]

The bomb itself is contained in a device at the top of a tower 500 ft High. Tanks move into the blast area and officers are to occupy trenches only 2,600 yards from the bomb the – closest ever in a test. Army personnel with recording equipment wait for zero hour as others check their cameras. And now the bomb – the marvel and the horror of our time is exploded inside the Holocaust. Cameras record the havoc.

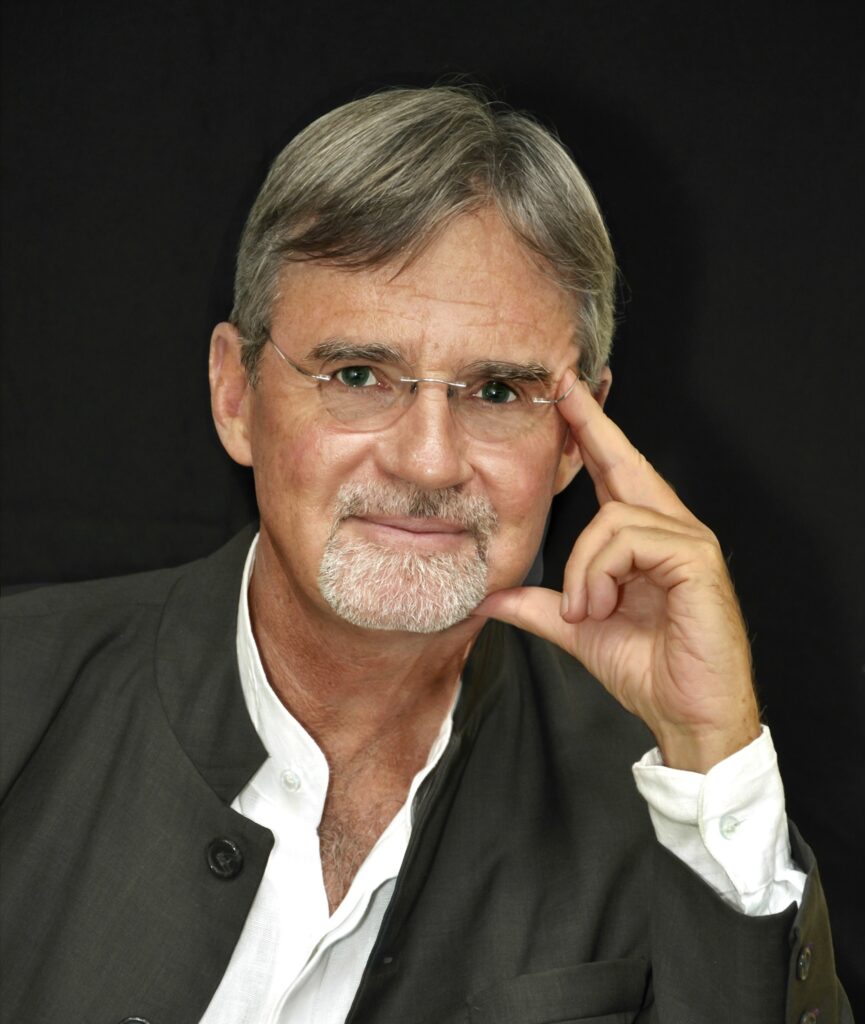

Rebecca Naomi Jones: Joining us is Kai Bird, executive director and distinguished lecturer at CUNY Graduate Center’s Leon Levy Center for Biography, and Pulitzer-Prize winning co-author of American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Kai Bird: He was born here in New York City. His father was a German immigrant of Jewish ancestry. His mother was also of German ancestry, Jewish, and born in Baltimore. But they actually raised their son—both sons, Robert and Frank—in the Ethical Culture Society, sent them to the Ethical Culture School. And this was a break-off from Reform Judaism. It was sort of a secular religion that emphasized ethical behavior, progressive political values, science, education—it was, at the turn of the century, an extremely progressive experiment in secular culture and philosophy. And it still exists today, of course.

And so Oppenheimer grew up knowing he was of Jewish ancestry, but he really didn’t think of himself as Jewish. Others did. And as a young man at Harvard, for instance, where he spent three years getting his BA in chemistry, he encountered social antisemitism. And as he matured—after Germany, where he also encountered antisemitism—in the thirties, he became more and more politically active and eventually had quite left-wing political views, and he was very concerned by the rise of fascism. And he personally spent his own money to help rescue German immigrants and bring them to America and settle them. So he was sympathetic to the plight of European Jewry, but he was not really Jewish in a religious sense.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: In 1942, General Leslie Groves, head of the Manhattan Project, sought someone to be the scientific director of the top secret government effort to build an atomic bomb. He traveled all over the country interviewing the nation’s best scientists and Nobel Prize winners. His search brought him to U.C. Berkeley, where 38-year old Oppenheimer worked as a professor in the theoretical physics department he helped found.

Kai Bird: Now, these were two opposites. They were like oil and water. General Groves was a gruff Army general—actually a colonel at that point—and very conservative politically. He was unhappy at being appointed to this position. He actually wanted a combat position, you know, leading troops into battle. But he had just finished building the Pentagon and done so in record time. And it was the largest building in the world at the time. And so he was appointed, as someone with an engineering background, to head the Manhattan Project as such.

And in his first meeting with Oppenheimer, he took a liking to him. He saw how ambitious he was. He saw also that this was one of the few physicists that he had talked to who could speak to him in plain English. He realized that Oppenheimer was a polymath, that he actually loved literature and poetry—wrote poetry. He was a humanist. He was interested in the human condition in a philosophical sense. And he could see the charisma in this young man.

But what really clinched the decision to hire Oppenheimer was that Robert Oppenheimer turned to him and said, I know that you are very concerned about security. Well, this is what you need to do.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: Oppenheimer proposed a plan to bring all the scientists into a remote area, located in Los Alamos, New Mexico. There, Groves could build a secret city surrounded by barbed wire, and inside, the scientists would be free to collaborate, argue, and experiment.

Kai Bird: And it just happened, of course, that the spot that Oppenheimer had in mind was only forty miles down the road from his beloved ranch in New Mexico where he retreated every summer to go horseback riding and—so this is how he combined in his life his love for physics and his love for New Mexico. And he got the job. And everyone says that it was a brilliant choice, that the atomic bomb never would have been built as quickly—two and a half years, as it was—if anyone else had been chosen.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: To build the secret city and laboratory, the government required the eviction of residents of Los Alamos. This included Pueblo communities who lived in this region for many generations, descendants of the Hispano homesteaders who had arrived in Los Alamos in the early 20th century, and the Los Alamos Ranch School, which was shut down and converted to the laboratory. Many of the evicted residents ultimately returned and took jobs in service to the Manhattan Project – it was their only option if they wanted to remain in their hometown and make a living.

The work began quickly, and within six months, more than 1,000 scientists had been hired. And by the spring of 1945, more than 6,000 Manhattan Project workers were living in the barbed wire city in Los Alamos. There were also even more workers at secret labs in Hanford, Washington, and Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

Kai Bird: They considered themselves to be in a race with the Germans to produce this weapon. But by April, May, Germany was defeated. By May, Hitler was dead. And there was actually a meeting—impromptu meeting among all the scientists at Los Alamos, held without Oppenheimer’s endorsement but he allowed the meeting to take place, to discuss the future of civilization and the gadget. And they were asking tough questions like, why are we working so hard to build this weapon of mass destruction, this terrible weapon, when we know Germany is defeated? And we know that the war in Japan—against Japan is still going on, but they’re not capable—we don’t think they have a project to develop the weapon. So why are we so hard at work on this?

And Oppenheimer stood at the back of the meeting, and only at the right moment, after everyone had had their piece, did he step forward, and he reminded everyone of what Niels Bohr, the grandfather of quantum physics, the Danish physicist, had said when he arrived in Los Alamos on the last day of 1943. And his one question was, Robert, tell me, is it big enough? Is it big enough to end all war? Is it going to be such a terrible weapon that humanity will understand that we cannot have total warfare like this ever again because that would be Armageddon?

And so Oppenheimer was making the argument to his fellow scientists that we have to continue working on this in May, June, July of ‘45 because it’s important that humanity understand the enormity of what we’ve discovered, understand the terribleness of this weapon, and they will only understand if it’s demonstrated, probably in combat—meaning on a city because there is no target large enough to demonstrate the destructive power of this weapon than a whole city. This was a powerful argument in some ways. And only one physicist ever quit at Los Alamos. It was Joseph Rotblat. The others continued to work.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: While Oppenheimer and his team were confident that the enriched uranium weapon they created worked, they needed to test the plutonium weapon. 210 miles south of Los Alamos, at 5:30am on July 16, 1945, the Trinity Test was conducted.

Manhattan Project leaders, staff, and scientists watched with their breath held as the device was detonated. In the quiet New Mexico desert, a mushroom cloud exploded over the pre-dawn sky, and an immediate, unrelenting heat seared everything in its path. In the distance, a tower vaporized. The staff watched in awe as the ground around the explosion turned to wispy green sand. The test was a success, and the bombs were ready for use.

For Oppenheimer and his team, seeing the true destructive power of the bomb for the first time was as sobering as it was gratifying.

Kai Bird: He’s walking to work in Los Alamos one day after the Trinity test, and he turns to his secretary at the time, Anne Wilson, who’s walking with him. And suddenly, she hears him saying to himself, muttering, Those poor little people. Those poor little people. And she stops him and says, Robert, what are you talking about? And he explains, Well, the Trinity test was more than successful, and now this weapon is going to be used on a city in Japan. And the victims are going to be poor little people, women and children and old men, and very few soldiers. So he was already worrying about this.

Archival Audio, Truman Radio Report to the Nation:

The world will note that the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, a military base. That was because we wished in this first attack to avoid, insofar as possible, the killing of civilians. But that attack is only a warning of things to come. If Japan does not surrender, bombs will have to be dropped on her war industries and, unfortunately, thousands of civilian lives will be lost. I urge Japanese civilians to leave industrial cities immediately, and save themselves from destruction.

I realize the tragic significance of the atomic bomb.

Its production and its use were not lightly undertaken by this Government. But we knew that our enemies were on the search for it. We know now how close they were to finding it. And we knew the disaster which would come to this nation, and to all peace-loving nations, to all civilization, if they had found it first.

That is why we felt compelled to undertake the long and uncertain and costly labor of discovery and production.

We won the race of discovery against the Germans.

Having found the bomb we have used it. We have used it against those who attacked us without warning at Pearl Harbor, against those who have starved and beaten and executed American prisoners of war, against those who have abandoned all pretense of obeying international laws of warfare. We have used it in order to shorten the agony of war, in order to save the lives of thousands and thousands of young Americans.

We shall continue to use it until we completely destroy Japan’s power to make war. Only a Japanese surrender will stop us.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: On August 15, 1945, Japanese Emperor Hirohito announced his nation’s surrender, and on September 2, the official surrender documents were signed.

Years later, Oppenheimer reflected on the role he played in World War II.

Archival Audio, Oppenheimer Reflects on WWII:

Reporter: Looking back now, do you think that our country’s use of the bomb was necessary?

Oppenheimer: I believe that the view, which I learned from many, but above all from General Marshall and from Colonel Stimson, the Secretary of War, the view that they had, that we would have to fight our way to the main island, and that it would involve a slaughter of Americans and Japanese on a massive scale, was arrived at by them in good faith, with regret, and on the best evidence that they then had. To that alternative, I think the bomb was an enormous relief. The war had started in 39. It had seen the death of tens of millions. It had seen brutality and degradation, which had no place in the middle of the 20th century.

And the ending of the war by this means, certainly cruel, was not undertaken lightly. But I am not, as of today, confident that a better course was then open.

I have not a very good answer to this question.

Kai Bird: So this is a very complicated man. He’s capable of doing his duty, providing this terrible weapon to the generals who are going to use it, to President Truman who’s going to order its use. And yet he was also capable, that very same week, of worrying about the morality, about the victims, about the tragedy of all this.

So after the war, he was determined never again to work on nuclear weapons, and he was determined to try to educate the public about the danger of these weapons. And he went around giving speeches within three months of Hiroshima in which he says, these are weapons for aggressors. These are weapons of terror. And they were used in the first instance on an already defeated enemy. And he argued for international controls and an agreement to ban these weapons. But he lost this political argument in the aftermath of World War II. The Americans had a monopoly, and they wanted to use that monopoly diplomatically in their relations. They thought it would help them in their relations with the Soviet Union.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: Oppenheimer returned to teaching at CalTech, but soon found himself unfulfilled. In 1947, he accepted a directorship at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University, at the request of Lewis Strauss, a Naval veteran, philanthropist, government official, and Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission.

Kai Bird: Strauss was then chairman of the board of trustees at the Institute. But Oppenheimer had a tendency—and he did this with Strauss—to insult or be rude to men in authority, particularly men in authority who sometimes—who showed any evidence that they thought that they were on his level. On the other hand, Oppenheimer could be very sweet and kind and gentle and patient with strangers on the street that he met or students that he was teaching. But he had an issue with men in authority. And he went out of his way after—in the late forties to sort of be rude to Strauss. So he created personal enmity between them in their relationship.

And then he and Strauss clearly disagreed over the use, the development, and reliance on nuclear weapons. Oppenheimer was constantly warning politicians in Washington, don’t think of these weapons as defensive. They’re not going to defend America. They’re actually weapons of terror, and we need to find a way to put international controls on them. And he opposed the development of the hydrogen bomb even after the Soviets exploded their own atomic bomb in 1949. And he argued against the development of the H-bomb, but Truman ignored him and authorized a crash program to develop a hydrogen bomb, a bomb that had the potential of being a thousand times more destructive than the bomb used on Hiroshima. And Oppenheimer saw no use for it. But Strauss did. And Strauss thought that Oppenheimer’s opposition to the H-bomb was evidence of, perhaps, his disloyalty. Perhaps he was actually a spy. Perhaps his political sympathies in the thirties were more than just political sympathies. Maybe he was a real Communist.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: Strauss’s deep animosity for, and distrust of, Oppenheimer continued to grow, and suspicions further deepened when it was discovered that Klaus Fuchs, a German theoretical physicist and Manhattan Project scientist, had been spying for the Soviet Union. In 1953, Strauss devised a plan to – in the words of physicist Edward Teller – quote “defrock him in his own church.”

In December, Strauss presented Oppenheimer with a letter listing all evidence of disloyalty, and informing him that his security file had been re-evaluated. Rather than give up his security clearance, Oppenheimer chose to fight the charges, and in 1954, a month-long hearing commenced.

Kai Bird: And he was naive in that Strauss had it all stacked against him. He picked the judges, he picked the prosecutor as such, and there were no judicial guarantees. The FBI was wiretapping Oppenheimer’s lawyer, who was not allowed to read the FBI evidence that was being submitted against him. It was a complete kangaroo court that Strauss orchestrated. And indeed, after a month of testimony, the panel—the security panel voted 2 to 1 to strip Oppenheimer of his security clearance. And then Strauss went a further step and leaked the entire transcript of the month-long security hearing to The New York Times, publicly humiliating Oppenheimer, revealing episodes from his personal life, his love affairs, and sort of the uncontested evidence that he had been disloyal.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: The investigations into Oppenheimer and his Communist ties occurred during the reign of Joseph McCarthy, a relatively unknown senator from Wisconsin who rose in prominence in 1950 after claiming to have evidence of a spy ring in the US state department.

Kai Bird: This took place in the spring of ’54, at the same time—shortly before and virtually at the same time as the Army-McCarthy hearings in which McCarthy eventually sort of humiliated himself. But the release of the transcript of what happened to Oppenheimer in the security hearing—the publication of that in newspapers across the country really sort of sent a message to the whole country that this scientist who had once—you know, in 1945, ‘46, ‘47, he’d been on the cover of Time and Newsweek, but nine years later, he was brought down in this security hearing, and his loyalty, his patriotism as an American, were questioned. So he became, I would argue, the chief celebrity victim of the whole McCarthy era.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: Oppenheimer, who had become one of the United States’ most famous public intellectuals and advisor to presidents and generals, became something of a persona non grata. He was disinvited from speaking engagements, and with the loss of his security clearance, he could no longer advise world leaders as he once had. He spent most of the rest of his life in Saint John in the Virgin Islands, and passed away in 1967, at the age of 62.

Kai Bird: And unfortunately, this sent a message to scientists in particular to beware of getting out of your narrow lane of expertise. Beware of sounding off like a public intellectual about policy or politics. Beware of talking about nuclear weapons in general and their morality because you could be tarred and feathered. And we’re still paying for that today, I think.

Rebecca Naomi Jones: From the American Jewish Historical Society, I’m Rebecca Naomi Jones. This episode was written by executive director Gemma R. Birnbaum. Recording, sound design, and mixing were done at Sound Lounge. Archival material is courtesy of the collections of the American Jewish Historical Society, British Pathé, the US National Archives, the CBS News Archive, and the Screen Gems Collection at the Harry S. Truman Library.

For episode transcripts, additional resources, and links to the collections featured in this episode, visit ajhs.org/podcasts. If you enjoyed this episode, please leave us a rating and review, which helps others discover our series.