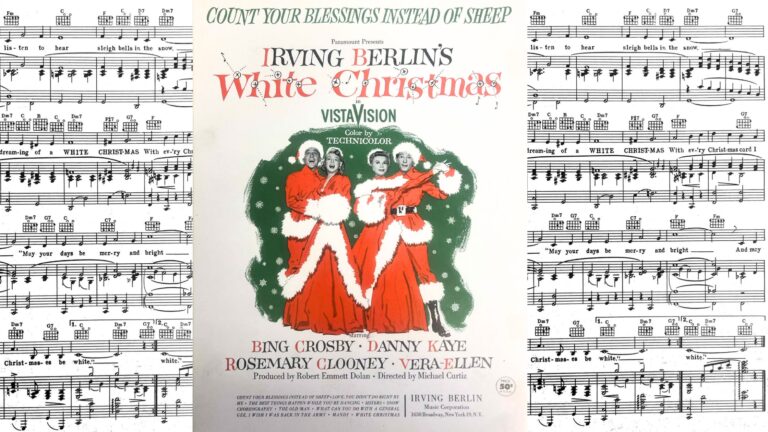

In the early 1970s, poor Jews living in the Dorchester section of Boston faced a pressing crisis. Youth gangs had ransacked their synagogues, firebombed their homes, and assaulted elderly residents, violent acts that recalled earlier clashes of the forties and fifties. In one family’s living room, intruders scrawled profanities and threats on the walls urging Jews to leave. Dorchester was a neighborhood rocked by sweeping demographic changes, intercommunal animosities, and economic adversity, but it was also a site primed for “Jewish defenders” to perform heroics. Acknowledging the disturbances in Boston, the recently established Jewish Defense League (JDL) arrived at the scene with guns and gusto. They organized patrols and vowed that “in Dorchester, and wherever Jews are threatened,” the JDL would respond.

“Move Jew”: photograph of Dorchester vandalism, Records of the Jewish Defense League, I-374, Box 1

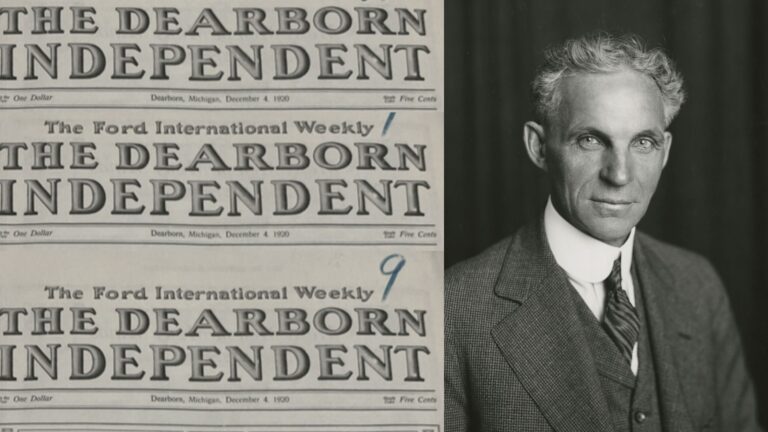

Founded in 1968 by Rabbi Meir Kahane, the JDL promoted militancy and masculinity as the solution to antisemitism and urban crime. Kahane’s vision of Jewish self-defense, modeled after the Black Panther Party, involved inverting the bookish image of Jewish males that had been baked into American popular culture. In contrast, a Jewish defender was to be virile, pugnacious, and proud of their Jewish identity. Marty Lewinter, a Brooklyn College student and JDLer, said it best: “a Jew can’t just keep his nose in his books and mind his own business anymore. People won’t let you.” Lewinter and other city-dwelling Jews attended JDL training camps to develop skills in hand-to-hand combat and rifle shooting.

JDL training camp snapshot, Records of the Jewish Defense League, I-374, Box 1

The JDL cited legitimate instances of antisemitism as a motivator, but the group had also emerged out of bitterness following the midcentury Civil Rights Movement. Some adherents felt that Jewish activists had supported the Black freedom struggle only to be alienated by “Black militants” like the Panthers. Others had resented broad liberal initiatives and complained that Jewish agencies should “primarily serve the JEWISH community.” Though many ethnic communities had “turned inward” during the sixties and championed their own specific goals, the JDL took such ideas to extremes. Kahane insisted publicly that “the Jew owes nothing to the Black man,” and stoked fears of Black delinquency. The JDL’s racist incitements – and terroristic campaigns – earned the group a spot on the FBI’s watchlist.

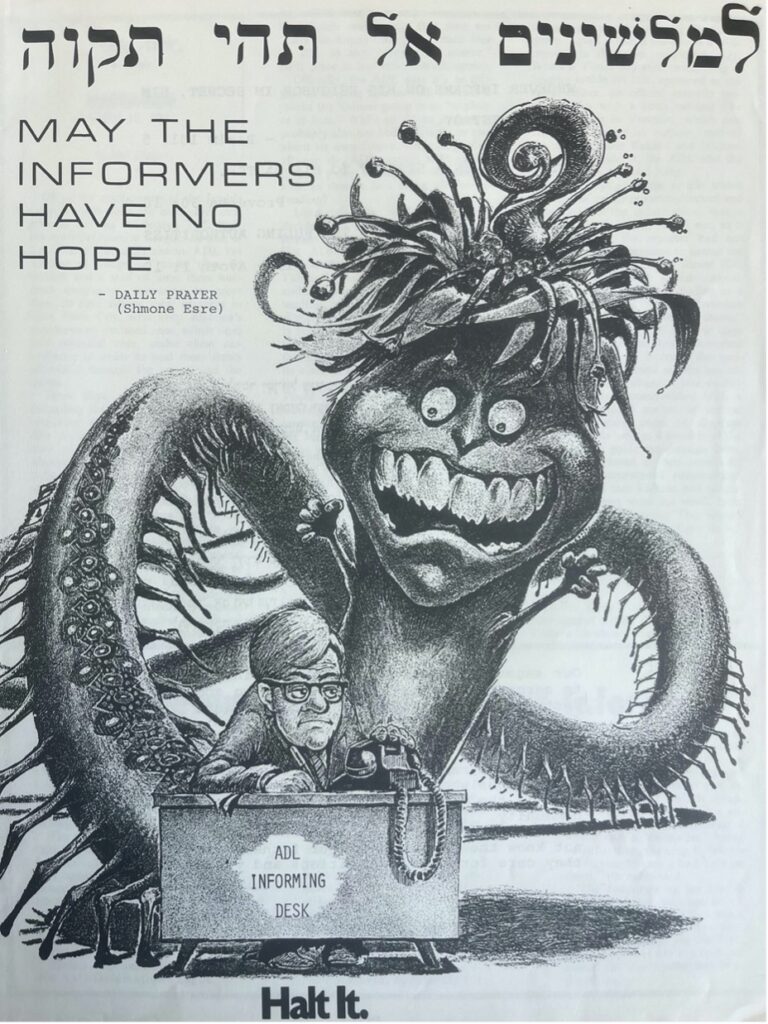

The JDL quarreled often with the “Jewish establishment,” mainstream Jewish advocacy groups that balked at Kahane’s aggressiveness. The American Jewish Committee repudiated “the lawlessness and self-defeating conduct of the JDL,” while rabbis in New York urged their colleagues to boycott the organization. Tensions escalated in 1971, when JDL supporters invaded the offices of New York’s Board of Rabbis and wrecked telephones, desks, and files. The Anti-Defamation League later provided the names of JDL leaders to the FBI, sparking accusations that establishment officials were traitorous “informers.” Despite the establishment’s misgivings about the JDL, leaders recognized why Kahane’s extreme measures resonated with some individuals. Haskell Lazare, an American Jewish Committee director, lamented that “Jewish agencies have lost touch with the rank and file,” failing to deal with communal difficulties “in the neighborhoods or the streets.” Jews in transitional neighborhoods like Dorchester concurred, blasting “white-collar” leaders for neglecting working-class concerns.

The JDL’s cartoon lambasting the ADL, Records of the Jewish Defense League, I-374, Box 1

On matters of crime, social scientists explained that severe poverty had bred violence – and elderly, defenseless Jews were often the easiest targets for muggings. There was little room for such nuance in the JDL’s assessment of Jewish life in America. Warning of imminent social collapse, Kahane insisted that because “Jewish neighborhoods are integrated,” militant Black youths would “practice terror.” In addition to race-baiting, Kahane exploited memory of the Holocaust to accrue support. The JDL propagated myths that German Jews had not resisted their oppression under the Nazis. Kahane’s catchphrase, “Never Again,” signified that no Jew would face a similar fate so long as the Jewish Defense League existed.

Advertisement for a JDL poster, “Never Again,” in JDL’s publication Iton, Records of the Jewish Defense League, I-374, Box 1

Much to the dismay of activists, the JDL had also hijacked the American Soviet Jewry Movement. Claiming to care for Jews trapped within the repressive Soviet regime, the JDL bombed multiple Soviet offices in America. The Jewish mainstream again condemned their strategies, arguing that such “bully-boy tactics” were counterproductive to the larger cause of freeing Soviet Jews. Facing criminal charges, Kahane fled to Israel where he repeatedly broke laws before serving in the government in the mid-1980s. The JDL movement persisted in America, marked by relentless violence, inflammatory rhetoric about Arab and Black Americans, and contentious claims that their methods would ensure Jewish safety.

For more from the Records of the Jewish Defense League, view the finding aid here.