The success of the MAX/HBO series, The Gilded Age, has people pondering, “What was up with the Jews during this period?” The answer, frankly, is, “What was not up during this period with the Jews of America?” First, the American Jewish Historical Society (AJHS) is itself a Gilded Age institution. Founded in 1892 by the most gilded of Jews of the time, Oscar Straus and Cyrus Adler. According to Leonard L. Milberg’s foreword to Yearning to Breathe Free: Jews in Gilded Age America Essays by Twenty Scholars.

“…the AJHS… began with a burst of energy. Responding to an invitation from the ubiquitous Cyrus Adler, the voice of Conservative Jewry who had affiliations with both Johns Hopkins and the Smithsonian Institution, a group of forty-one men, including a few prominent Christians, assembled at the Jewish Theological Seminary to discuss the establishment of a societydedicated to the history of the Jews in the Americas. German-born Oscar Straus, the wealthy scion of the Macy’s department store family and a lawyer active in the administrations of Grover Cleveland and Theodore Roosevelt, was elected chairman of the nascent group, and Cyrus Adler was chosen as secretary-treasurer. Other board members included Professor John McMaster; Harvard’s Charles Gross; history of early America Herbert Friedenwald; transportation engineer Mendes Cohen of Baltimore; Lewis Dembitz of Louisville (uncle of Louis Brandeis), Professor Morris Jastrow, holder of the Semitic chair at the University of Pennsylvania; Reform rabbi Bernhard Felsenthal of Chicago; London-born New York rabbi Maurice Harris; and the formidable Henrietta Szold.”

Milberg reminds us that many of these men served on the boards of Jewish institutions, including the Jewish Publication Society (JPS, founded 1888), the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS founded 1887), and later, the American Jewish Committee (AJC founded in 1906 and presided by Louis Marshall)., And of course, Szold went on to found Hadassah: The Women’s Zionist Organization in 1912.

AJHS was established in 1892, determined to prove that Jews were stalwarts of America, even before its founding. From the first Jews who settled in New Amsterdam in 1654, to Mordecai Sheftall’s work during the American Revolution. Jew’s were also part of America’s tragedies, after the Civil War, some Jews in the North had to reconcile with their Jewish Confederate relatives and vice versa.

From the end of the Civil War in 1865 and the end of Reconstruction in 1877, through the later Progressive Era of the late 1890s to 1920s, some American Jews during the “Gilded Age” of 1865 to 1900 acquired wealth primarily in the merchant and peddler trades. Some became Captains of Industry in railroads, oil, and investments, while many others labored in tenements, worked in trades, or became the doctors, lawyers, and teachers of New York City. The Jewish population was small and primarily centered, but not limited to, New York City.

Jews began pursuing their own civil rights organization during this period —The Board of Delegates of American Israelites. The Board first came together to combat the taking of an Italian-Jewish child baptized in Italy, named Edgardo Mortara, and raised as a Catholic. The Board worked on numerous cases of what they deemed violated the civil rights of Jews, including during the Civil War when General Grant issued and quickly withdrew his General Order 11, banning Jews from Grant’s military districts for corruption and illicit cotton trading. The Board had five objectives: obtaining and collecting statistical information; the appointment of an arbitration committee to settle disputes between congregations; to promote religious education and training of men for the rabbinate as well as the work force; to “keep a watchful eye on occurrences at home and abroad, and see that the civil and religious rights of Israelites were not being encroached and to communicate that to the authorities when needed”; and lastly, to “establish and continue to communicate with other like-minded Jewish organizations” throughout the world and the U.S. The Board worked with Sir Moses Montefiore of England, the British Board of Deputies, and the French Alliance Israelite Universelle. The Board supported Jews in Ottoman Palestine, contributed funds to schools, intervened on behalf of Turkish Jews, spoke out against the changing of the Jews’ Hospital in NYC to Mt. Sinai, and defended Alfred Dreyfus in 1894, who was accused of being a German spy in France.

These overlapping eras found first and second-generation Jews worried not only about their own American story, but also how American society would assimilate European Jews migrating to the States. They established agencies such as the Industrial Removal Organization and provided education in farming and labor through the Baron de Hirsch Fund. Professor Hasia Diner argues in a Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era article entitled, “The Encounter Between Jews and America in the Gilded and Progressive Era,” that Jews in America greatly benefitted from five factors: “…the emergence of America as an engine of dynamic economic development, the mass migration of tens of millions of Europeans, the new reification of privilege along the color line, the triumph of non-ideological politics, and the defanging of religion, Protestantism in particular.” Diner also notes that 19th-century Jewish Americans were able to assimilate easier in some respects than their Italian and Irish migration peers, and avoided the clashes between Christian Catholics and Christian Protestants, combined with a determined belief in the separation of church and state in the U.S.

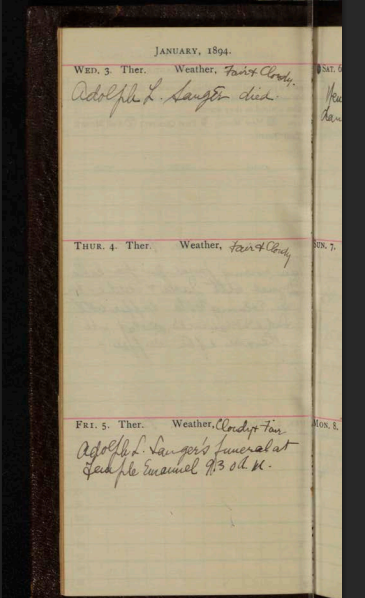

The term “Gilded Age” derives from the 1873 book by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Walker, The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. This long, 600-page book had two parts: the first by Twain and the second by Walker, both of which skewered the rise of those who pursued wealth and social position, corrupt politicians, and shady industrialization. So far in the HBO drama, Jews have not been portrayed in New York’s high society. While it is true that social classes often socialize in strict circles, Gilded Age Jews and Christians did mingle socially, as can be seen in Florence Lowenstein Marshall’s calendar diaries. Wealth did not prevent upperclass Jews from experiencing discrimination in Gentile society. Jews were banned from universities, businesses, and certain social and athletic clubs. Merchant and banker Joseph Seligman, was denied a room at Saratoga’s Grand Union Hotel in 1877, the controversy ignited a wave of criticism and debate.

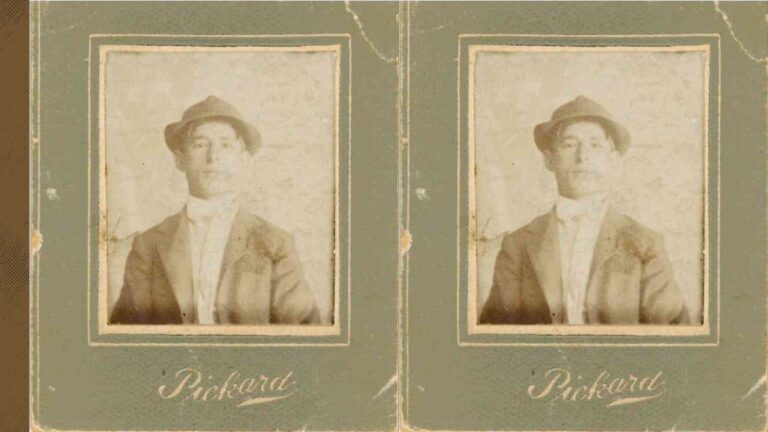

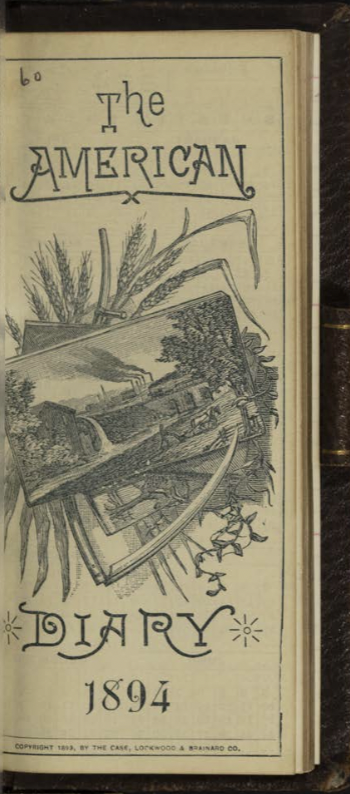

In 2019, lay historian and great-grandson of Louis and Florence Lowenstein Marshall, Peter Schweitzer, donated 20 original diary calendars and recreated the events of three years (1896, 1898, 1908) when those diaries of Florence’s were unable to be found. Schweitzer meticulously annotated Florence’s handwritten diaries, creating a manuscript documenting the personal and professional lives of Florence and Louis.

Florence was born to a peddler from Bavaria, Benedict Lowenstein (1831-1879), and Sophia Mendelson Lowenstein (1847-1884). Benedict originally landed in New Orleans in 1854, settling in Memphis, TN, where he expanded his merchant business into the B. Lowenstein and Brothers Department Stores. The business opened in several Southern towns as the Lowensteins followed the same route as the Lehman Brothers of Montgomery, AL. The business bought raw cotton, sent it North for processing into linens, and then back to the South for sale. After the Civil War, the business itself shifted to New York City.

Benedict and Sophia were married on October 30, 1867, in New York City, and had six children: one boy (Leon Benedict, 1869-1949) and five girls (Adelaide, 1868; Sarah, 1870; Florence, 1873; Elsie, 1877; and Beatrice, 1879). Benedict was not a well man and suffered from heart-related ailments. He died while at a health spa in Wiesbaden, Germany, with his wife and children. Sophia was pregnant with her youngest daughter, Beatrice. Sophia and the children moved in with Benedict’s bachelor brother, Bernard, who treated them like both an uncle and father, particularly after Sophia died in 1884. Sophia’s sister, Sarah, married Maurice Untermyer, a lawyer whom Louis would later join in the law firm of Guggenheimer, Untermyer & Marshall. Maurice’s father, Samuel, had been a plantation owner in the South and a lieutenant officer under the Confederate flag.

The life of the Lowenstein family was documented somewhat by Florence’s youngest sister, Beatrice, who married Judah Magnes and lived in Palestine for most of her married life. Peter Schweitzer includes portions of Beatrice’s autobiography, highlighting the gilded yet progressive lives some of the sisters led. They lived on 52nd Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, with both corners being occupied by Vanderbilts. Beatrice’s sisters were much older and acted as parents to her as Florence, Elsie, and Beatrice attended the Normal School for Women (now Hunter College).

Louis Marshall’s parents, Jacob (1829-1914) and Zilli Straus (1826-1910), were first-generation Americans, like Florence’s, and were also from Bavaria. Jacob, like Benedict, became a merchant after years of working on the Erie Canal and settling in Syracuse. Louis’s family grew up devoutly Orthodox, while Florence’s family only rarely delved into Judaism when she was younger. However, they attended synagogue for High Holy Days and Hebrew schooling at Temple Emanu-El. Florence gave the Salutatory address in the closing exercises on June 5, 1887. Louis’s family settled in Syracuse, NY, while Florence lived in NYC on the same street as the Vanderbilts. Jacob was a wool and leather merchant, and, like Benedict’s family after his death, he established his own business in Syracuse, which is now a luxury apartment building. After Zilli’s death, Jacob moved to Philadelphia, where he died while living with his daughter.

American Jewish History, Vol. 94, No. 1, “Two Jewish Lawyers Named Louis” (Courtesy Peter Schweitzer)

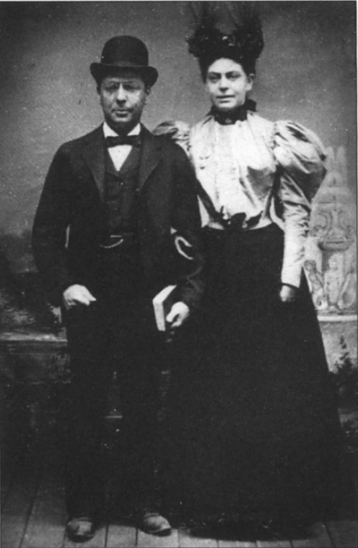

Louis and Florence’s life together began at a meeting more than likely set up by family and friends. Their first date was at the Metropolitan Opera House, which played a significant role not only in HBO/MAX’s Gilded Age series but also in the world of the upper classes of New York. They would have four children: James, Ruth, Robert, and George. Sadly, Florence died in 1916 of cancer. She never once mentioned she was dying or really sick in her diaries. Louis would live until 1929.

Florence’s diaries, as well as Peter Schweitzer’s manuscript, can be viewed online, both the original diaries and the detailed annotations. Among Florence’s notes on who came for dinner, what plays they saw, what committee meetings she went to, what childhood vaccines she gave her children and their illnesses, and when she changed the curtains from Summer to Winter and back again, and their trips to upstate New York. She notes that when Louis went away, what he was doing and what he was working on. Schweitzer then fleshes out his great-grandmother’s notations, bringing them to life through the events surrounding Louis’s work.

If HBO/MAX is looking to expand its show in the coming seasons, writers may find inspiration with the Marshall family. If you’re a scholar of this era, Florence’s diaries and Schweitzer’s annotations are a perfect melding of resources for the Jewish Gilded Age.

Florence Lowenstein Marshall Diaries P-1046 can be viewed here

________________________

Sources

B. Lowenstein and Brothers. Application for Historic Preservation. https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/66a2ea66-f216-4ef0-adc0-ad6139571f28

B. Lowenstein and Brothers Building. Memphis, TN. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/B._Lowenstein_%26_Brothers_Building

B. Lowenstein Brothers Department Stores. Urban Exploration Resource. https://www.uer.ca/locations/show.asp?locid=25395 Accessed 1 October 2025.

Board of Delegates of American Israelites, I-3, American Jewish Historical Society.

Diner, Hasia. “The Encounter between Jews and America in the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era.” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, January 2012, Vol. 11, No. 1 (January 2012), pp. 3-25. jstor.org/stable/23249056. Accessed 27 August 2025.

Jacob Marshall and Son Building. VIP Structures. https://www.vipstructures.com/preserving-history-while-embracing-change-at-one-websters-landing/ Accessed 3/10/2025.

Milberg, Leonard L. “Foreword.” Yearning to Breathe Free: Jews in the Gilded Age Essays by Twenty Scholars. New Jersey: Princeton University, 2022, p. xi.

Sarna, Jonathan D. “Two Jewish Lawyers Named Louis.” American Jewish History 94, no. 1/2 (2008): 1–19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23887663.

Twain, Mark, and Charles Dudley Walker. The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. 1873 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Gilded_Age:_A_Tale_of_Today

Young, Michelle. Guide to the Gilded Age Mansions of 5th Avenue’s Millionaire Row. 6SqFt. https://www.6sqft.com/a-guide-to-the-gilded-age-mansions-of-5th-avenues-millionaire-row/ Accessed 10/3/2025.