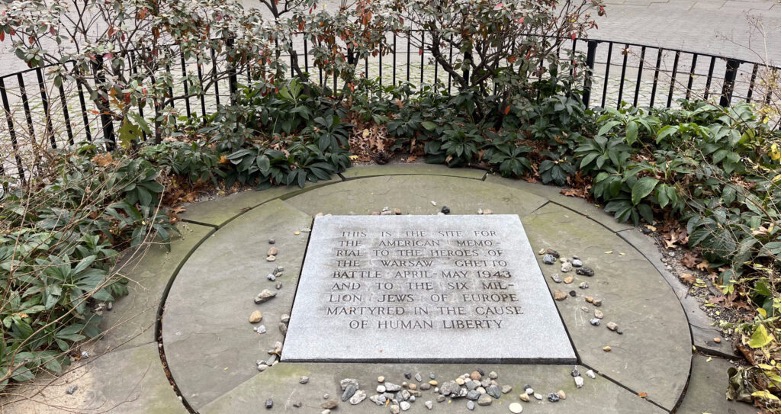

In October 1947, thousands of New York City residents gathered at Riverside Park to witness the dedication of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising Memorial. A modest granite plaque on the ground, the memorial honors “the heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto battle” of April-May 1943, when Jews staged an armed resistance against the Nazis. Despite every disadvantage, the Jewish combatants managed to sustain the uprising for nearly a month. The Germans responded ruthlessly, demolishing the ghetto and killing or deporting its remaining inhabitants. Years later, American Jewish leaders resolved to commemorate these fallen fighters whose defiance in the face of death represented “one of the great moments in the history of the Jewish people.”

Today, Holocaust memorials or museums appear in most states, but these sites of recognition have often attracted controversy. The plaque at Riverside Park, while appropriately understated, was intended to be the cornerstone of a larger monument that never materialized. In the 1960s, Jews clashed with New York City officials over plans to update the existing memorial space. A Jewish group, the Committee for the Six Million, offered to cover the costs of a statue that would honor the lives lost in the Holocaust. Their favored design depicted a bronze figure “engulfed in thorns and flames, sharply leaning to the front, as if about to fall.” The city’s Art Commission rejected the proposal, complaining that it “might distress children in the park.” A tamer alternative, consisting of two 26-foot-high scrolls, was also refused for being “excessively and unnecessarily large.”

More than disagreements over style and scale, these rejections reflected discomfort with acknowledging historical atrocities against minorities. Eleanor Platt, a renowned sculptor and member of the Art Commission, warned that such a monument would “set a highly regrettable precedent” in that “it might provide an opening for ‘other special groups’ that wanted to erect memorials on public land.” Jewish critics of the decision argued that city parks were already filled with war monuments “dealing with violent themes,” with little concern for how they would upset parkgoers. Platt responded that such monuments were “generally patriotic” and depicted moments of “American history.” [1]

For Jewish survivors of the Holocaust, many of whom made new lives in New York, these tragic histories were an incontrovertible part of their story. Dr. Joachim Prinz, President of the American Jewish Congress and a German-Jewish refugee, expressed his “profound shock” at the Art Commission’s rulings. He insisted that it was reasonable to construct a monument in New York, which then had “the largest Jewish community in the world.” No statue was ever built in Riverside Park, though the plaque remains.

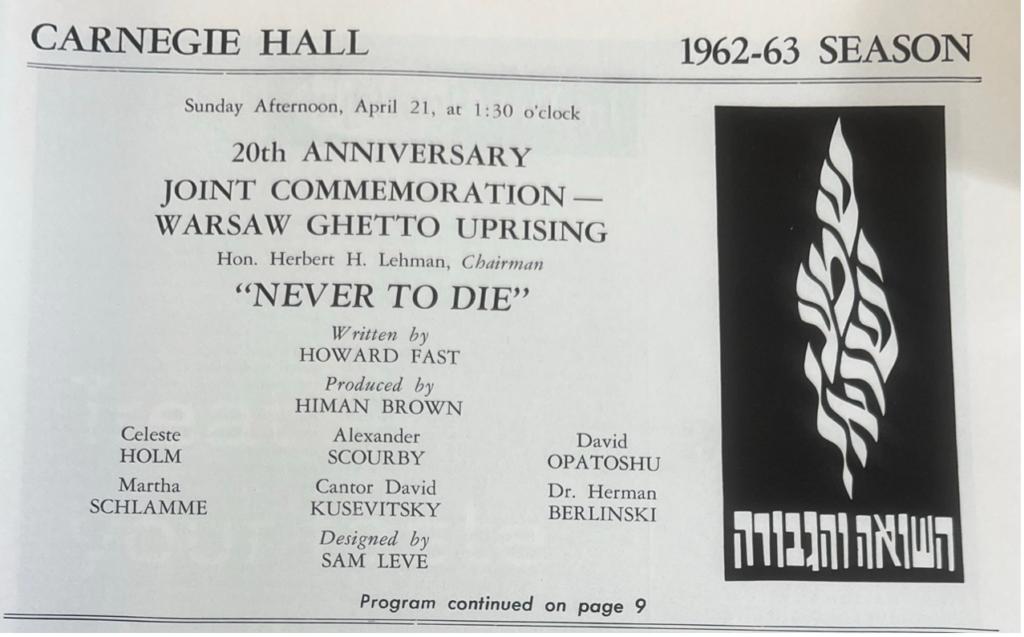

These conflicts notwithstanding, Jews found other ways to commemorate the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising during its twentieth anniversary in 1963. Answering their requests for public recognition, President John F. Kennedy issued Proclamation 3523, which invited “the people of the United States” to observe the occasion “with appropriate ceremonies and activities.” Every major Jewish organization in the country united to form the Joint Commemoration of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising for the purpose of hosting a program in New York’s Carnegie Hall.

The ceremony would recount “the courage, the songs, and the sacrifice of the Warsaw Ghetto fighters” with a dramatic script written by Jewish author Howard Fast. Organizers sought celebrity participants – Gregory Peck, Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, and Katherine Hepburn were some of the loftier names thrown around – and settled on actors Alexander Scourby and Celeste Holm. The latter had won an Oscar for her performance in Gentleman’s Agreement, a film about the insidious nature of antisemitism. In her opening statement, Holm recited a poem: “A people of many memories / Will some say too many memories? / But there is a time for memory / As well as a time for forgetfulness / A time for sowing and a time for reaping / And for laughter, there is also a time / And a time for weeping.”

The thousands who crowded Carnegie Hall listened to Jewish speakers reflect on the lessons of the uprising. The first Jewish governor of New York, Herbert Lehman, impressed upon listeners that such “heroic deeds” should remind “every Jewish parent” and “every Jewish child” of their responsibilities to uphold freedom. Other Jewish civic leaders emphasized the duties of Christian America. During a 1965 ceremony at Temple Beth Sholom in Rockland County, New York, Shad Polier charged that “the United States was at fault,” referring to “restrictive immigration quotas” that left hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees trapped. Following his speech, the temple’s theater group reenacted scenes from the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, “complete with the sounds of Nazi trucks and tanks.” Though dramatizations were unable to capture the horrors of the Holocaust, such exercises provided American Jews with the chance to imagine what their European counterparts had endured.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising has featured prominently in Holocaust commemoration for several reasons. Rabbi Arthur Gilbert, who became active in the Anti-Defamation League in the 1960s, observed that “it’s horrible to think of so many Jews being slaughtered by Nazis,” and that the uprising allowed “some Jews to think of themselves as having power,” however limited. Gilbert further speculated that the larger American society was “uncomfortable with the guilt that must be engendered at the movie clips of starving concentration camp victims.” He imagined that Christians worldwide shared a vested interested in perpetuating the image of the dignified Jewish soldier, portrayals that helped alleviate their guilt for abandoning Jews during the Nazi regime. Above all, Jews felt it was crucial to memorialize the tragic heroes of Warsaw to dispel myths that the victims had died passively, like “sheep to the slaughter.” In America, they worked tirelessly to make these commemorations happen so that Jewish history could serve as a model for the ongoing struggle against injustice.

View the Records of the American Jewish Congress, I-77

View the Shad Polier Papers, P-572

[1] “City Rejects Park Memorials to Slain Jews,” The New York Times, February 11, 1965.