This September marks 109 years since the United States’ first attempt at a federal Child Labor Law. The law had a brief life, being passed in 1916 and enacted in 1917, only to be declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court just nine months later in 1918, as the country considered its priorities amid the Great War.1 It wasn’t until 1938 that Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which defines “oppressive child labor” as any individual employed under the age of 16 or anyone between the ages of 16 and 18 employed in an occupation deemed hazardous by the Secretary of Labor.2

From the time of the Industrial Revolution until the integration of the Fair Labor Standards Act, child labor was commonplace, and regulation was sorely lacking.3 In 1912, President William Howard Taft created the Children’s Bureau (CB) to investigate and report on matters of child welfare.4 Investigators in the Child Labor Division had limited power to alter the conditions they found in the field. However, they could open the path for private philanthropies or progressive organizations to intervene. Miss Cecelia Razovsky of Missouri is one such investigator.

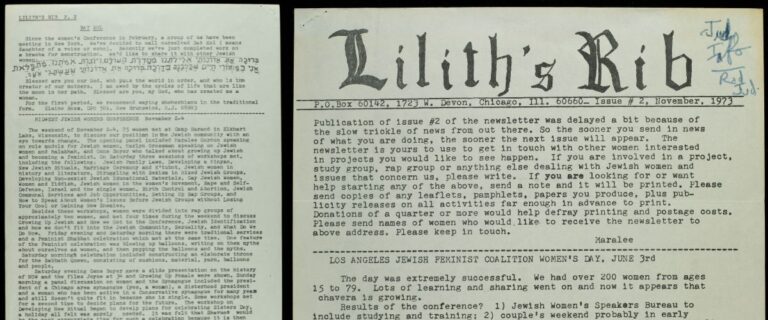

The American Jewish Historical Society is proud to steward the personal papers of Cecelia Razovsky, which contain a wealth of material documenting not only her personal life during a time of rapid industrial change but also her work as an activist for child labor reform and refugee relief later in the century. Cecelia was born to immigrant parents in St. Louis and began working at the age of 12, sewing buttons in a clothing factory. She continued working through her adolescence as a salesgirl, waitress, laundress, stenographer, clerk, and secretary – as was common for children at the time (1898) – to supplement her parents’ income. Cecelia is an illustrative example of how children contributed to the workforce at the turn of the century. You can view a digitized version of her CV in a recent blog post by AJHS’s summer intern, Alexandra Grunfeld.

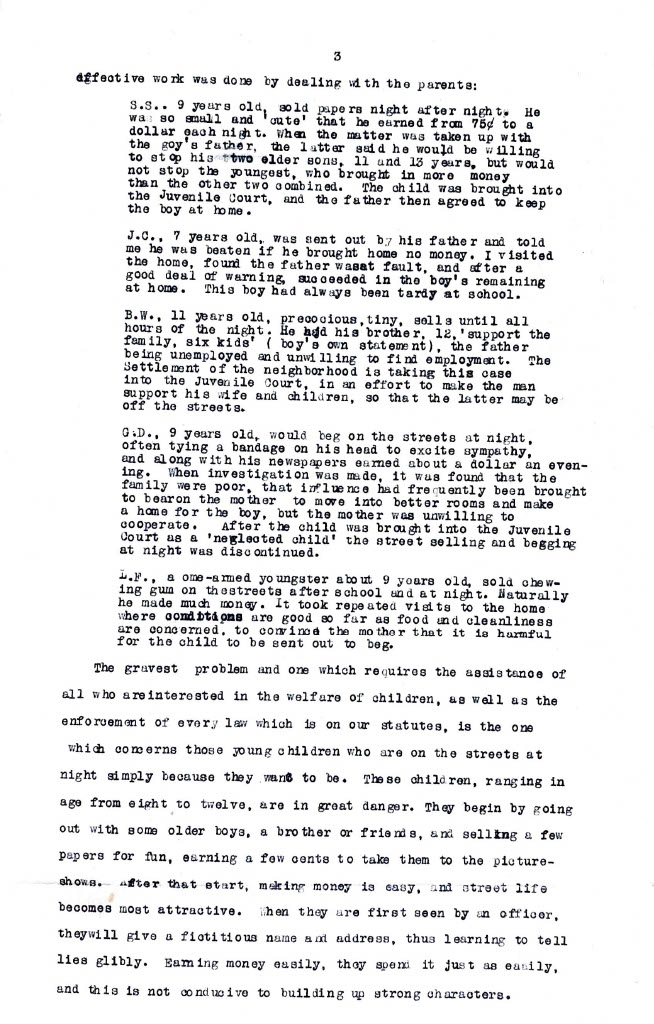

Cecelia excelled professionally and successfully transitioned from child laborer to child advocate; her personal papers include a vast collection of investigative reports that shed light on the varying conditions of child labor at the beginning of the 20th century. In 1911, she took a job as an Attendance Officer for the St. Louis Board of Education. In her 1912 report on street trades in St. Louis, Cecelia remarked that certain classmates from her own high school had worked as newsboys in the evenings to earn extra cash and had gone on to become “physicians, lawyers, engineers, and businessmen.” However, in examining street trades, she did not find evidence of a positive environment for early development. In a batch of cases where charities and higher authorities had intervened for the welfare of a child, Cecelia wrote of the case of an 11 year old boy “precocious, tiny, sells until all hours of the night. He and his brother, 12, support the family, six kids…the settlement of the neighborhood is taking this case into the Juvenile Court…”5

Cecelia concludes her report with the caution that while the incentive of income is a driving force for many children and their parents to work in the evening, the ‘gravest problem’ is that many of these ‘youngsters’ find street life attractive, fun and exciting. Her suggestion for a solution is to open public spaces where boys and girls can spend their time away from the streets, ‘giving them profitable outlets for their superfluous energy’: evening playgrounds, game rooms in the public library, free moving pictures and throwing open the public schools.6

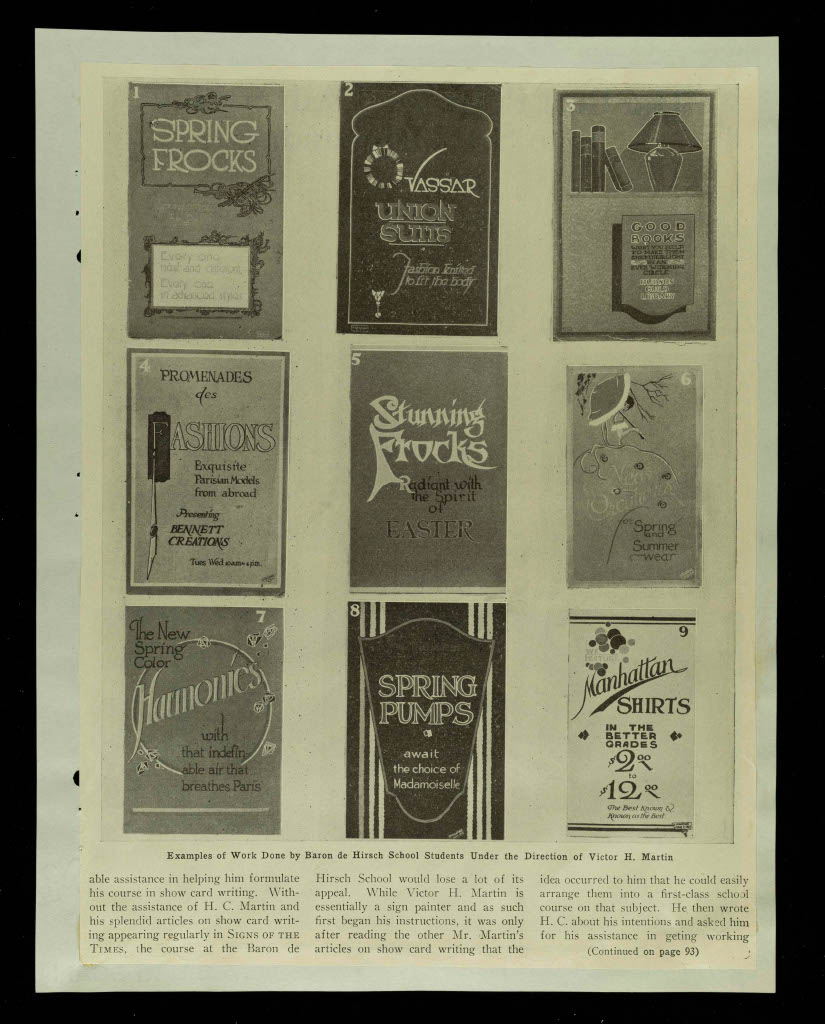

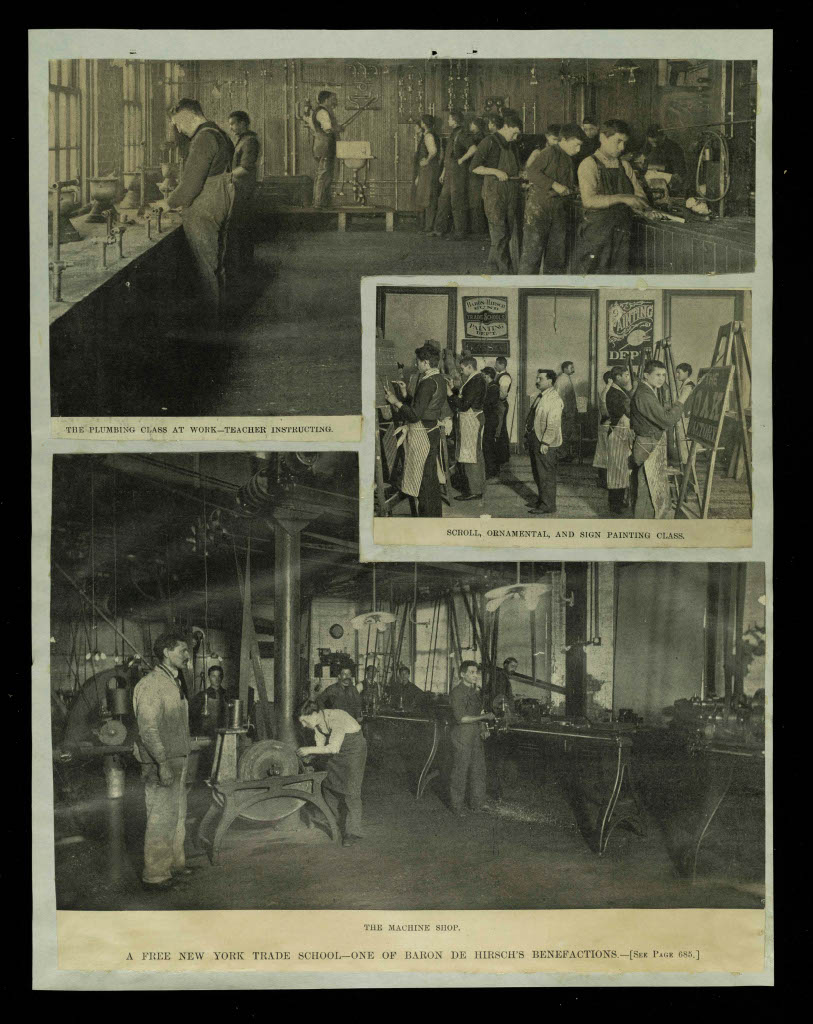

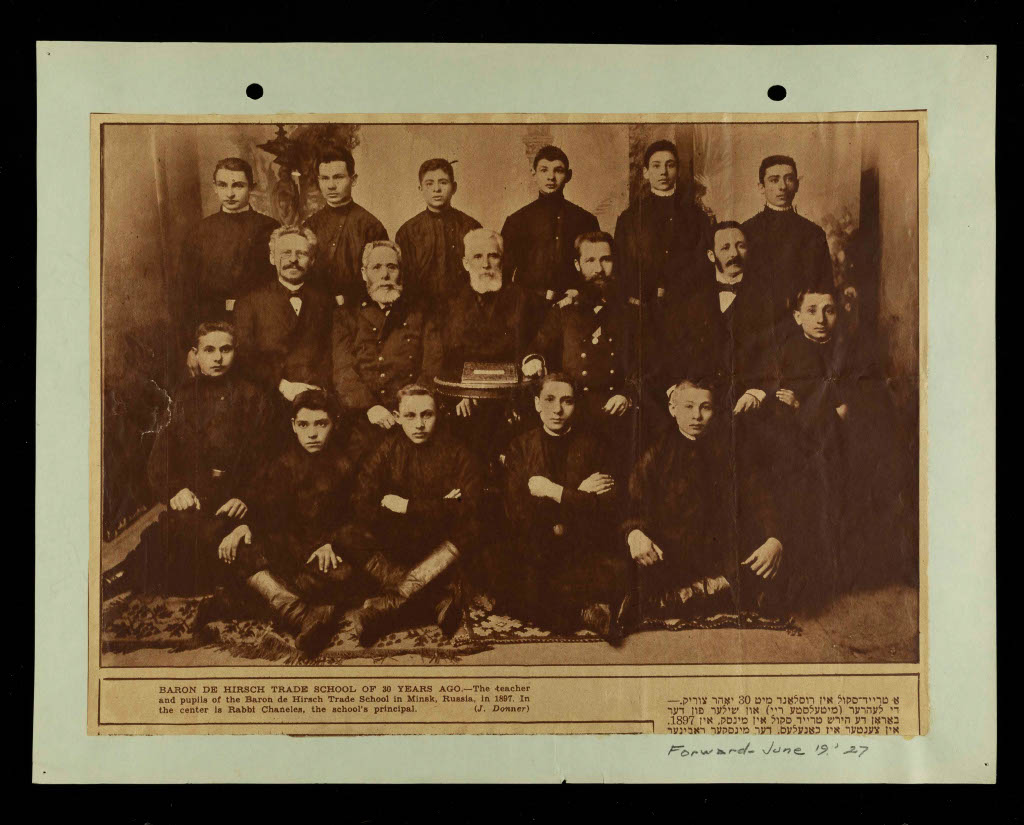

In New York City, where over two million Jewish immigrants had settled between 1881 and 1924,7 philanthropic organizations played a significant role in helping improve the lives of children and families burdened by low wages and harsh working conditions. One such institution, which actively disrupted the trend of unskilled child labor among new arrivals in America, was the Baron de Hirsch Trade School, run by the Baron de Hirsch Fund in Manhattan. The school taught young Jewish men a variety of useful trades, enabling them to earn higher salaries or start their own businesses upon graduating into the workforce. Courses included carpentry, plumbing, machinery, and sign and house painting. Minutes from a meeting of the Committee on Education, held November 23, 1906, reported “ninety per-cent of our pupils are wage earners before entrance to the school, and sacrifice a wage earning period to come to school.”8 In the same year, of the 294 enrolled students, 99 were aged 16 or younger.

The Baron de Hirsch Trade School not only provided young Jewish men with an excellent foundation for their chosen trade but also equipped them to become successful members of the community. The school exclusively catered to Russian or Romanian Jewish immigrants “who have been in America less than two years.”9 Students were also taught English and encouraged to develop a “high standard of American citizenship”.10 In a city where thousands of children worked every day laying bricks, sewing buttons, painting signs, keeping stables, packing fish and tanning leather, these skills were an invaluable resource to those fortunate enough to benefit from free enrollment.11 And in a climate where, as Cecelia Razovsky reported, children helped support their families through evening work that was often unskilled and low-earning, the Trade School was taking positive action to incentivize skilled labor and continued education for young men of a particularly vulnerable demographic.

The records of the Baron de Hirsch Fund I-80

The papers of Cecilia Razovsky P-290

________________________________________

- Woodrow Wilson and Julia Lathrop, Children’s Bureau, n.d., 13, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.mchlibrary.org/history/chbu/20483.PDF

↩︎ - Woodrow Wilson and Julia Lathrop, Children’s Bureau, n.d., 13, accessed August 18, 2025, https://www.mchlibrary.org/history/chbu/20483.PDF

↩︎ - Michael Schuman, “History of child labor in the United States—part 1: little children working,” Monthly Labor Review, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, January 2017, https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2017.1

↩︎ - “The Children’s Bureau,” SSA History, Social Security Administration, last modified [n.d.], accessed September 4, 2025, https://www.ssa.gov/history/childb1.html

↩︎ - Cecelia Razovsky, A Report of Investigations Made in the Downtown District of St. Louis During the Evening, with Reference to Street Trades, December 6, 1912, p. 3, box 3, folder 1, Papers of Cecelia Razovsky, American Jewish Historical Society, Center for Jewish History, New York, NY.

↩︎ - ibid, p. 4-5

↩︎ - Jewish Women’s Archive, “The Immigrant Experience in NYC, 1880–1920,” viewed July 30, 2025, https://jwa.org/article/immigrant-experience-in-nyc-1880-1920

↩︎ - Meeting Minutes of the Committee on Education, held November 23, 1906, p. 27, box 7, folder 6, Records of the Baron de Hirsch Fund, I-80, American Jewish Historical Society, Center for Jewish History, New York, NY

↩︎ - Teaching Trades to Hebrew Poor [newspaper clipping], p. 12, Series VI, “Histories: Articles – Published, 1895–1931,” Records of the Baron de Hirsch Fund, I-80, American Jewish Historical Society, Center for Jewish History, New York, NY.

↩︎ - Ibid. ↩︎

- Fast-Food New York: The Public Cost of Low‑Wage Jobs in the Fast‑Food Industry, (“Taxpayer Costs…” subtitle if any), Center for Labor and Unions or sponsoring organization, April 2014 (pdf), 14, accessed August 28, 2025, YoungWorkers.org, PDF file. ↩︎