The Jewish festival of Sukkot, celebrated in the autumn five days after Yom Kippur, is marked by several observances, including holding festive gatherings and meals in a temporary outdoor structure known as a “sukkah,” from which the holiday derives its name, and which symbolically hearkens back to the Exodus of Jews from Egypt and their reliance on temporary dwellings as they wandered the desert for 40 years after leaving Egypt.

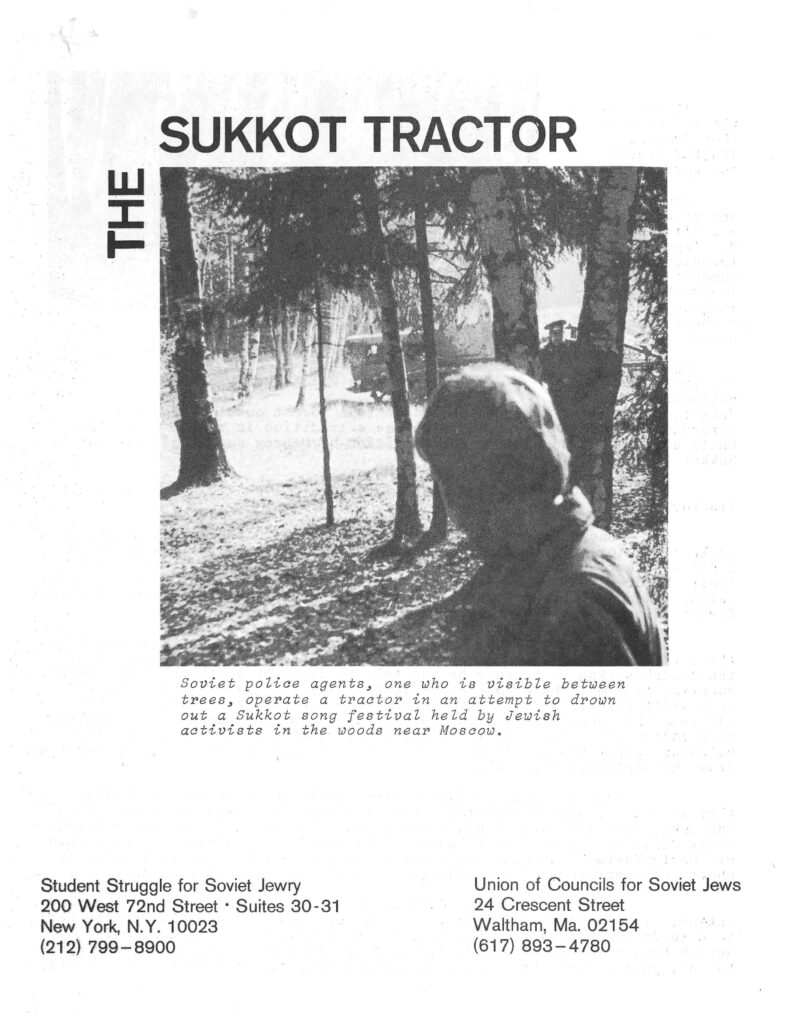

The Chicago Action for Soviet Jewry records, one of the remarkable collections housed in AJHS’s Archive of the American Soviet Jewry Movement, holds a striking leaflet entitled “The Sukkot Tractor.” Despite the whimsical-seeming name, the document, promulgated by two other Soviet Jewry activist organizations, Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry and Union of Councils for Soviet Jews, recounts a distressing episode for some Moscow Jews attempting to celebrate the beginning of Sukkot, in October 15, 1978.

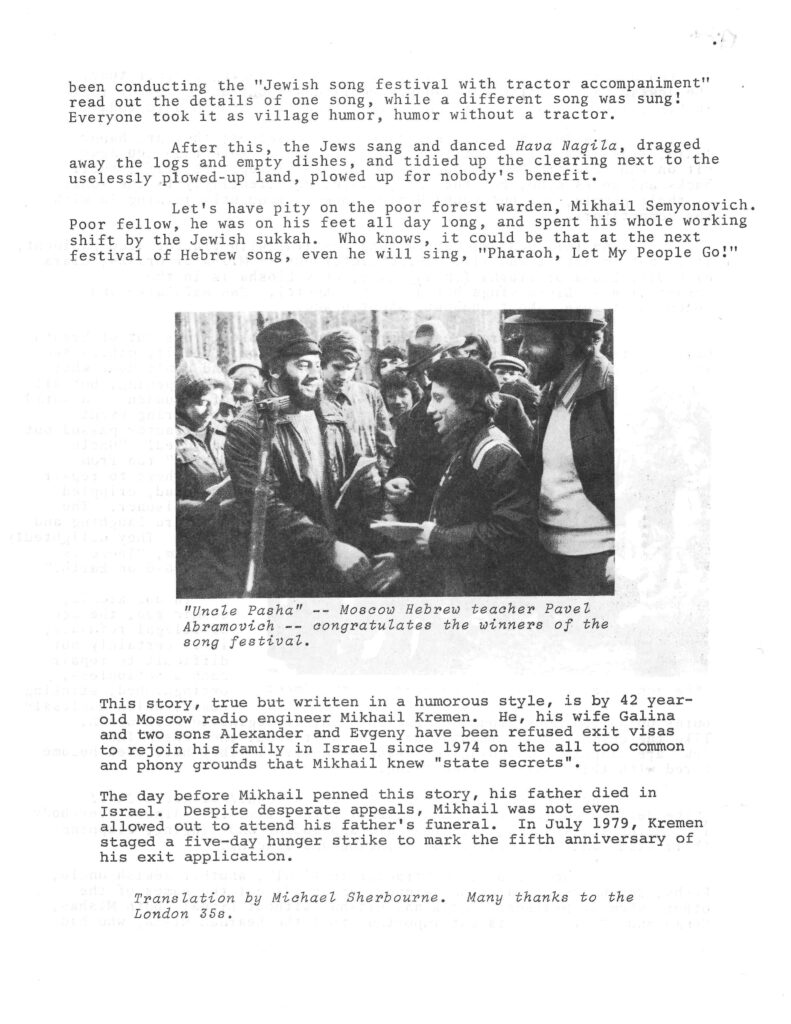

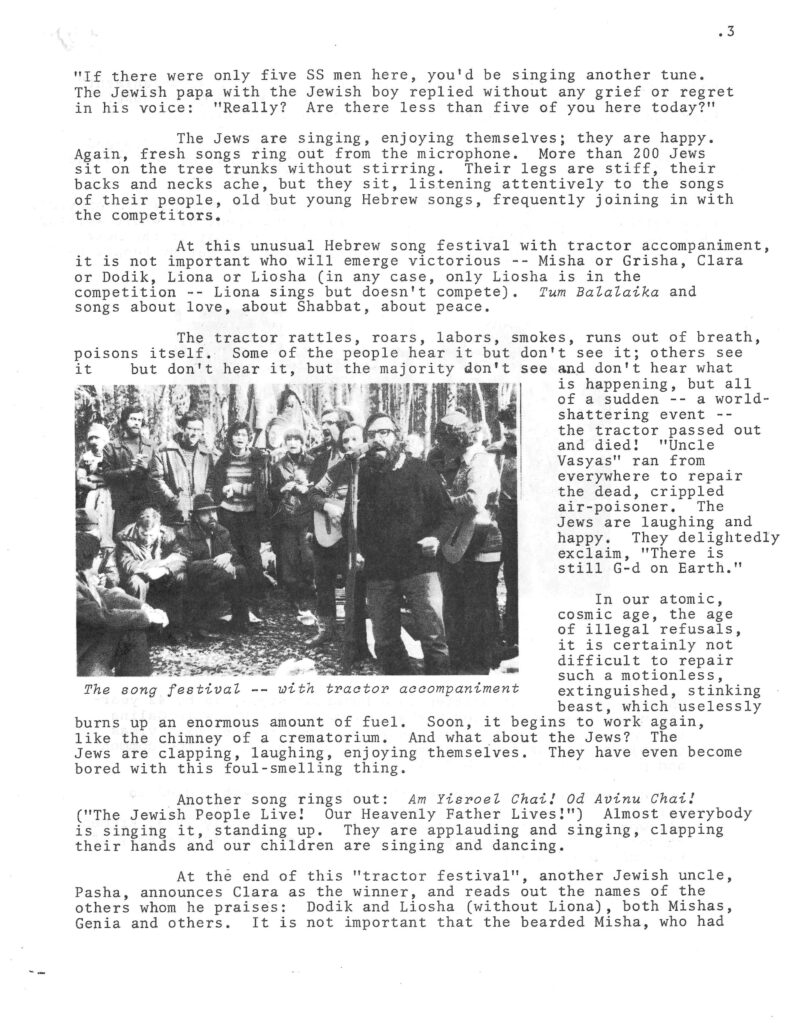

As 220 participants gathered in a forest outside Moscow to build a sukkah and sing Hebrew songs, a policeman began plowing the meadow nearby and then left the tractor running, presumably to disrupt the festivities. Those gathering to celebrate Sukkot persisted in singing and rejoicing even louder under these absurd circumstances; as the document wryly describes it, it was a “Jewish song festival with tractor accompaniment.”

“The Sukkot Tractor” characterizes the tractor as a “crippled air-poisoner,” in contrast with the participants “clapping, laughing, enjoying themselves.” The sardonic tone of this flier underscores the manifold resilience of Soviet Jewish communities, and underscores how this anecdote was simply one of countless obstacles and persecutions that Jews confronted under the Soviet regime.

The document’s conclusion registers very somberly, noting that the story is “true but written in a humorous style” by a Moscow radio engineer named Mikhail Kremen, who along with his family, had been refused an exit visa to Israel since 1974. The final paragraph reads:

The day before Mikhail penned this story, his father died in Israel. Despite desperate appeals, Mikhail was not even allowed out to attend his father’s funeral. In July 1979, Kremen staged a five-day hunger strike to mark the fifth anniversary of his exit application.